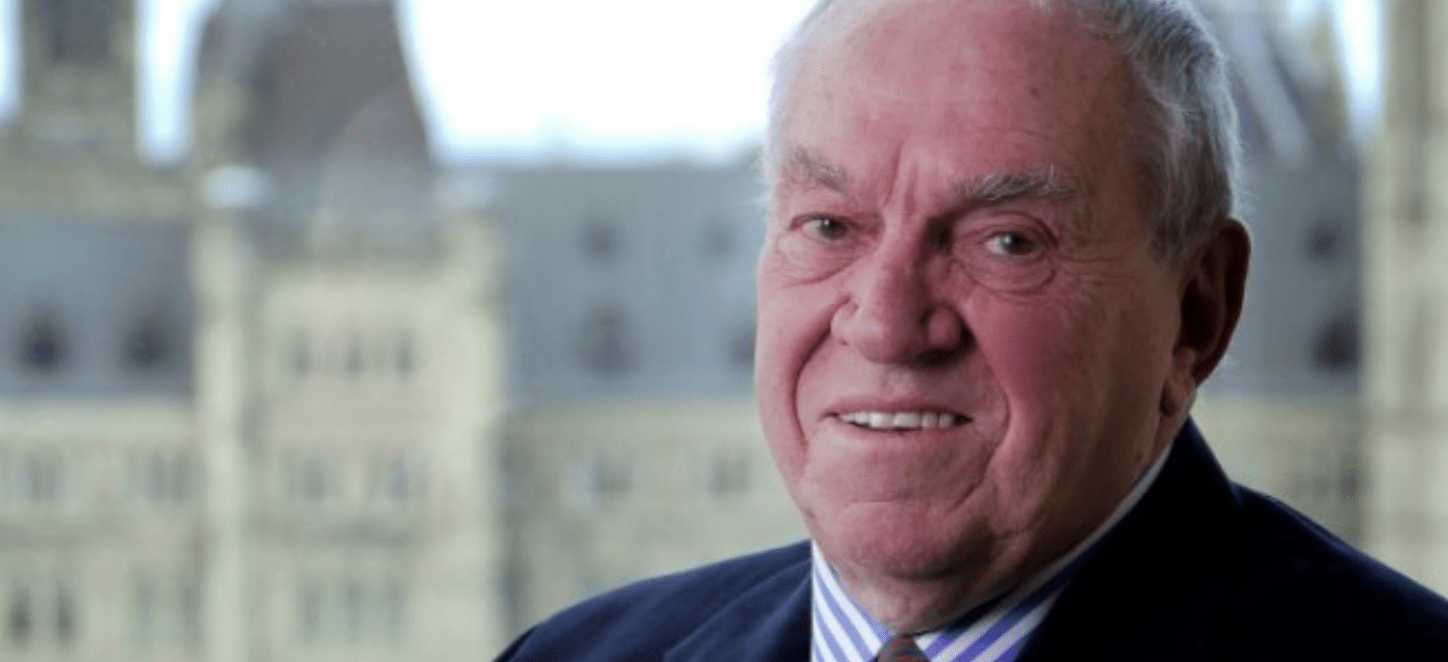

Working-Class Hero, International Statesman: Ed Broadbent, 1936-2024

Broadbent Institute

Broadbent Institute

By Robin V. Sears

January 11, 2024

Years ago, near the end of a political mission to Havana about the raging civil wars in Central America, Ed Broadbent was miffed. Here was Ed, an avid cigar smoker, having just spent three hours in a bilateral with Fidel Castro, and still not a Cohiba or a Monte Cristo in sight.

As we prepared for our early morning flight home, Broadbent railed at me, “You swore we would get cigars!” I bore my chagrin in silence then noticed a large black Mercedes had pulled up in the driveway. Out came two large Cuban security guys. They were lugging a wooden box the size of a small coffin.

They plunked it down on the floor in front of us. Ed smiled at me with mounting anticipation as he struggled with the bows and wrapping like a child on Christmas morning. Inside were hundred and hundreds of cigars, from tiny to gigante. Broadbent kept it locked in his office on the Hill for years.

That an unassuming working-class boy from Oshawa grew into a pivotal figure in Canadian life and an international statesman is a testament to Ed Broadbent’s skill and determination, but also to Canada. Ed was an unlikely, beloved Canadian political leader. Trained as an academic, he was recruited as a New Democratic Party candidate in 1968.

Broadbent’s great strength was that he straddled the two worlds of his blue-collar, auto-assembly home town of Oshawa — a.k.a. the Detroit of Canada — and his academic life in nearby Toronto, partly because he believed that if he could inhabit them both, they were not really divided. Not everyone agreed – he made his political champions in the United Auto Workers wince when, at his nomination meeting, he quoted C.W. Mills, a leading American sociologist, at length.

But that juxtaposition of political theory and its practical application — Broadbent’s intellectual residency in the Venn overlap between abstract principles and implementation — was what defined him as a politician. He didn’t care about winning for its own sake, he cared about winning for everyone else’s.

Ed Broadbent’s career was made of more highs and lows than the usual political rollercoaster. Narrowly elected, he was an instant hit as an MP. So much so, that he succumbed to the temptation to challenge David Lewis for the leadership after less than three years in the House and got clobbered. “That was the worst political decision of my life,” he would wryly concede for decades afterward.

His victory as party leader came in 1975, out of a wide and competitive field. This began his first resurrection of social democracy in Canada, and the start of his imprint on Canadian history. The NDP was in tough straits when he took office. After a glorious two years as the Liberals’ nudgers in the 1972 minority parliament, they won Petro Canada, public financing for elections and more than a dozen other important legislative victories. Then, they got thumped in the ensuing 1974 election.

The NDP had come close to a fatal division only a few years before in an intense internal battle between those who wanted a more nationalist, radical, and aggressive party and those who knew that would lead to it being crushed. The Waffle movement — “I’d rather waffle to the left, than waffle to the right” — launched fierce struggles for control of the party. Broadbent served as a sympathizer of many of its aims — especially on a national industrial strategy, a radical notion at the time, convention today. He also served as a bridge builder to the party establishment. He played an important peacemaking role in bringing the painful period to an end.

With many thanks to Terry Mosher

With many thanks to Terry Mosher

When Trudeau launched his battle to patriate the Canadian constitution and to create a Charter of Rights, Broadbent again played a key role in finding a path to success between dissenting premiers and the federal Liberals. One of the leaders of the anti-Charter coalition was the NDP’s own beloved Saskatchewan Premier Allan Blakeney.

Having led the party to its greatest victory in the 1980 election, and opened it to Quebec, Broadbent was thrown once more into an existential moment. The federal caucus, one current and one former premier, and the trade union movement were united on one side. The internal opposition led by the Saskatchewan NDP had won the support of much of the party’s grassroots.

Broadbent persuaded Trudeau to accept recognition of Indigenous rights in the Charter, to which he had previously been rigidly opposed. He won improvements in the clauses protecting women’s rights and clear definitions of the civil rights of all Canadians. These victories helped weaken the opponents’ case. That the Charter would not have made it into the essential pillar of Canadian democracy that it has become without Broadbent’s cool but insistent demand for changes, is incontestable.

He stepped down as leader in 1989, after the bitterly disappointing free trade election the year before. He was, as he said to friends at the time, “running out of gas.” This led to almost an entire decade of decline for the federal party. A series of poor leadership choices pushed party support into the single digits by the end of the 90s.

Broadbent once more stepped into uniform, as the party’s powerful and determined defender. He spotted Toronto alderman Jack Layton as key to the party’s revival. Endorsed him, worked for him, and then ran successfully as an MP in Ottawa Centre for him. He and Jack formed a key partnership in the revival, once more, of the NDP.

In his years of retirement, Ed launched the Canadian Centre for Rights and Democracy at the request of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. It was Canada’s first serious effort at offering Canadian values, and civil society support internationally. The Harper government killed it. Broadbent went on to found the Broadbent Institute, an education, training, research and advocacy think tank. Since 2011, it has grown into the most influential political think tank in the country.

Just last year, he published an intriguing form of political memoir, Seeking Social Democracy, a dialogue with three leading Canadian intellectuals about the events of his life and his reflection on them over his nearly half-century career.

Broadbent was a passionate man beneath his softer, smiling public demeanour. He cared deeply about the abuse of those not able to defend themselves on Canadian reserves, on Canadian streets, and internationally. He was an addicted cigar smoker until he had to quit; loved a glass of good wine and an evening of spirited discussion with friends. He loved jazz and fine art and travel. His private life was marked by deep loss, not once but twice he lost beloved partners. Married three times in total, with two children, he always picked himself up and moved on. Even in these last years of his life, he had found a new partner who brought him joy.

Ed Broadbent was the type of Canadian politician we have few of today. A fierce debater, never a spit-flecked angry partisan. A great believer in strong institutions, yet someone who would quietly work just as hard on the struggle of a single constituent. He loved and devoted himself to his party, but was respectful and friends with those in others. Brian Mulroney, Jean Chrétien, and Bill Davis were among his cross-bench friends.

Canada will mourn the passing of Ed Broadbent, yet we will all cherish his achievements, which have touched so many of our lives, for years to come.

Contributing Writer Robin V. Sears, now an independent communications consultant in Ottawa, was national director of the New Democratic Party of Canada during the Broadbent years.