Whistling Past the Tradeyard

By Douglas Porter

February 14, 2025

If misery loves company, then misery is pretty happy this week on the trade front. That sentence may be a little baffling, but so, too, is the outlook for tariffs and trade. It’s a strange world we find ourselves in where the U.S threatens pretty much every country with “reciprocal” tariffs, as soon as April 1, and that’s viewed as relatively good news by markets, since it leaves time for “negotiation”. (Air quotes are mine.) To wit, it was mostly onward and upward for global equities this week, bond yields ended flat to down despite a sour U.S. CPI result, and the U.S. dollar broadly faded. Even the Canadian dollar has rallied to its best level since early December at 70.6 cents (or $1.417/US$), rising almost 3% from just two weeks ago. Suffice it to say that markets are not overreacting to the threat of tariffs.

There are of course some solid fundamental factors that are keeping markets on the straight and narrow. The upswing in stocks to near-record highs following some softness around the turn of the year has been keyed by generally positive Q4 earnings. Treasuries were initially staggered by the surprisingly strong U.S. CPI, but were soothed by a no-worse PPI, and then truly calmed by soft retail sales. Fed Chair Powell’s mid-week Congressional testimony didn’t break any new ground, but reinforced the message that the FOMC could be patient and had the ability to respond to whatever surprises the economic data may have in store. After a brief trip above 4.65%, the 10-year yield ended well below 4.50%.

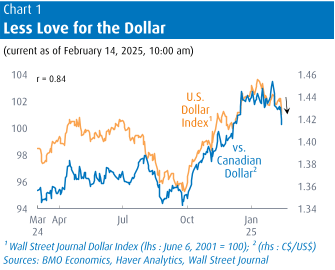

Currency markets are probably the most attuned to the trade outlook—one outlet suggested this week that a potential trade war had made currency traders cool again. After a nearly unbroken string of strength through the fall and early 2025, the U.S. dollar has clearly broken stride, falling by more than 2% on a weighted basis over the past month (Chart 1). The pullback comes despite the Fed moving to the sidelines and looking like it may be there for quite some time, even as rates continue to come down aggressively in most of the mature economies. The meaty CPI, which saw core inflation edge up to a 3.3% y/y pace, even prompted us to push back the next Fed cut until September. Yet, despite the potential for wider spreads between the U.S. and most major economies, and a steady drumbeat of trade threats, the dollar appears to have peaked.

So what explains the market’s seeming newfound nonchalance to trade concerns? There is the one train of thought that the end-result for U.S. tariffs will be much less fearsome than the current rhetoric, and/or won’t last long. That’s entirely possible, but probably shouldn’t be the operating assumption, given the sustained and enthusiastic nature of the threat. And, even as markets were breathing a sigh of relief this week, the reality is that 25% tariffs on steel and aluminum—no exemptions, no exceptions—are poised to land on March 12. Some have argued that the metals tariffs are aimed primarily at China, yet Canada is the number one external supplier of both, and by far on aluminum, and had been previously exempted due to the USMCA. Notably, these tariffs will be ‘stackable’, meaning that they will be on top of any other broader tariff measures imposed.

Moreover, the long list of grievances outlined during the announcement of reciprocal tariffs—even including VATs—suggests that almost every nation will face U.S. pressure. It may well be that the destination will be a universal tariff, given the complexity of sorting through the wide variety of tax, tariff and non-tariff measures in place around the world. U.S. officials cited the EU, Japan, India and Brazil as particularly vulnerable to new tariffs, but a special shout-out was also reserved for Canada. Still, holding out some hope that this really is mostly a negotiating tool, the President did suggest that if others brought down their tariffs, the U.S. would respond in kind.

Arguing on the side of “this is more than a bargaining chip” is the clear fact that many in Washington are looking approvingly at the potential tariff revenues. After the early intense focus on trade, the conversation is now shifting to the even knottier realm of the budget, taxes, and the debt ceiling. Almost lost amid all the other noise this week was the fact that the U.S. budget deficit rose to $840 billion in the first four months of the fiscal year, the widest gap on record over that period. That brought the 12-month rolling tally to $2.14 trillion, or just over 7% of the current level of GDP.

In very round numbers, total U.S. merchandise imports are currently $3.25 trillion, and a 10% universal tariff on such could potentially raise more than $300 billion in revenues (versus customs duties of $87 billion in the past year). Of course, there’s the small matter that imports could actually drop in the face of heavy tariffs, but revenues anywhere close to that tally look awfully tempting given the groaning budget deficit. We’ll point out that personal income taxes brought in $2.7 trillion in revenues in the past year, or more than 30 times the tariff intake. The conclusion is that while a broad-based tariff could raise some meaningful revenues, it would a) not be a costless exercise for the U.S. economy, putting upward pressure on inflation and downward pressure on growth, b) not alone bring the budget deficit to a comfortable level, and c) not come even close to beginning to replace the personal income tax haul.

The resiliency of the S&P 500 in the face of trade uncertainty may be somewhat understandable, but less so is the fast rebound in the TSX. The index moved within 0.4% of its all-time high on Thursday and remains up more than 20% y/y. Similar to the comeback in the loonie, Canadian equities are seemingly awaiting actions and not responding to words. That may well be the case for economic forecasts as well. The latest monthly Consensus Forecasts, conducted just this week, reveal that Canadian economists have only slightly marked down their view on domestic GDP growth to 1.5% this year and 1.7% next (we are two ticks higher on both). While each contributor likely has a slightly different approach to how they are handling the tariff threat, it’s pretty clear that no one has a full-on trade war built into their call—growth projections would be closer to zero or lower if that was the case.

However, that’s not to say that the economic outlook has dodged the trade uncertainty. Notably, the consensus outlook for Canadian GDP growth in 2025 has steadily weakened from 2.2% (in late 2023) to 1.5% now, even as the consensus on U.S. growth has gone in precisely the opposite direction over the same period from 1.6% to 2.2%. And that reversal in fortunes comes despite the much more aggressive rate cuts by the Bank of Canada (200 bps vs. 100 bps from the Fed).

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.