While America Tweeted: China, Trump and the Crisis of Democracy

Lisa Van Dusen/For The Hill Times

June 22, 2017

Since we seem to be living through a serious (also frequently un-serious) shift in geopolitical dynamics, it might be a good time to explore what the end of America’s post-Cold War unipolar dominance could mean for people other than the bad actors currently facilitating that end.

Graham Allison of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government has a new book, Destined for War: Can American and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? It asserts that the defining geopolitical question of our era is whether China’s rise will force a military confrontation with America.

China hasn’t spent the past two decades preparing for a military confrontation with America. China has spent the past two decades avoiding one by achieving dominance through other means.

While maintaining the posture of a “peaceful rise,” China has vastly expanded its economic influence through massive foreign investment, a practice now formalized with the creation of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the “One Belt, One Road” policy.

The most glaring recent examples of the link between Chinese money and the undermining of democracy include Greece’s blocking last week of an EU statement criticizing China’s human rights record. Among China’s major investments in Greece, it now owns the iconic Port of Piraeus. It’s a reminder, in the wake of the recent controversy in Ottawa over China’s bid to purchase of Norsat, that Chinese investment comes with political quid pro quos.

Other means have been less overt. As an official from the Australian Security Intelligence Organization told a parliamentary committee in that country last week, espionage is “extensive, unrelenting, and increasingly sophisticated” and poses as great a threat to national security as terrorism. “They try to influence our polity, bureaucracy, and civil society…and clandestinely interfere in Australia’s affairs,” ASIO official Heather Cook said. While Ms. Cooke did not name the perpetrators, the country’s former defence secretary, Dennis Richardson, has pointed the finger at China.

While the 2016 Russian interference narrative has monopolized attention in America’s current political crisis, China has benefited enormously from Donald Trump’s unlikely presidency—from his scrapping of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, to his trolling of NATO, to his plan to renege on the Paris agreement.

Most of all, hour after hour, and day after day, Trump makes democracy look ridiculous. And China fears democracy even more than Russia does. With a population of 1.4 billion people, more and more of whom are being lifted out of poverty in a transition that was once a precursor to demands for democracy, China values “stability above all else,” or wending yadao yiqie.

That policy drives its behaviour in ways that have been exported to other aspiring New World Order players such as Russia, Turkey, Hungary, and the Philippines on issues including internet restrictions, the invocation of “sovereignty” in the face of any criticism of human rights practices, the targeting of NGOs, and surveillance practices.

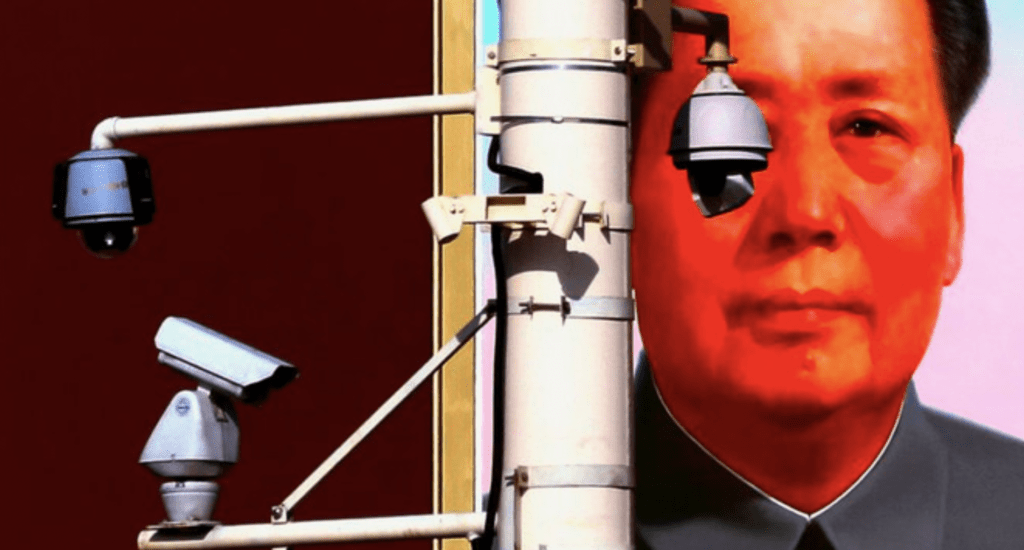

For a look at what China’s dominance might mean to daily life in a less democratic, subservient West, surveillance isn’t a bad place to start.

In Tibet, where 150 self-immolations have happened since 2009, neighbourhoods are divided into surveillance “grids”where grid managers monitor activity by video, cyber, and checkpoint control making more organized forms of protest and other dissent impossible. Chinese officials said when they set up the “Skynet” system in 2012 that it was installed to stop self-immolations in Tibet. The system went national in 2016. Not being a democracy, China doesn’t need terrorism as a premise to obliterate civil liberties in the name of security.

Never a neutral presence, surveillance can be used to harass, intimidate, coerce, discredit, and marginalize targets, especially journalists, activists, artists, writers, and anyone who expresses an opinion—especially the truth—embarrassing to people in power. It can be used to punish, censor, and virtually imprison a target without messy questions of legality.

As The New York Times reported Monday, Mexico is the latest nominal democracy to use technology to punish its critics, outside the bounds of law.

Like so many things, surveillance states are not what they used to be.

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor of Policy Magazine. She was Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.