What Got Done in Delhi: Takeaways from the 2023 G20 Leaders’ Summit

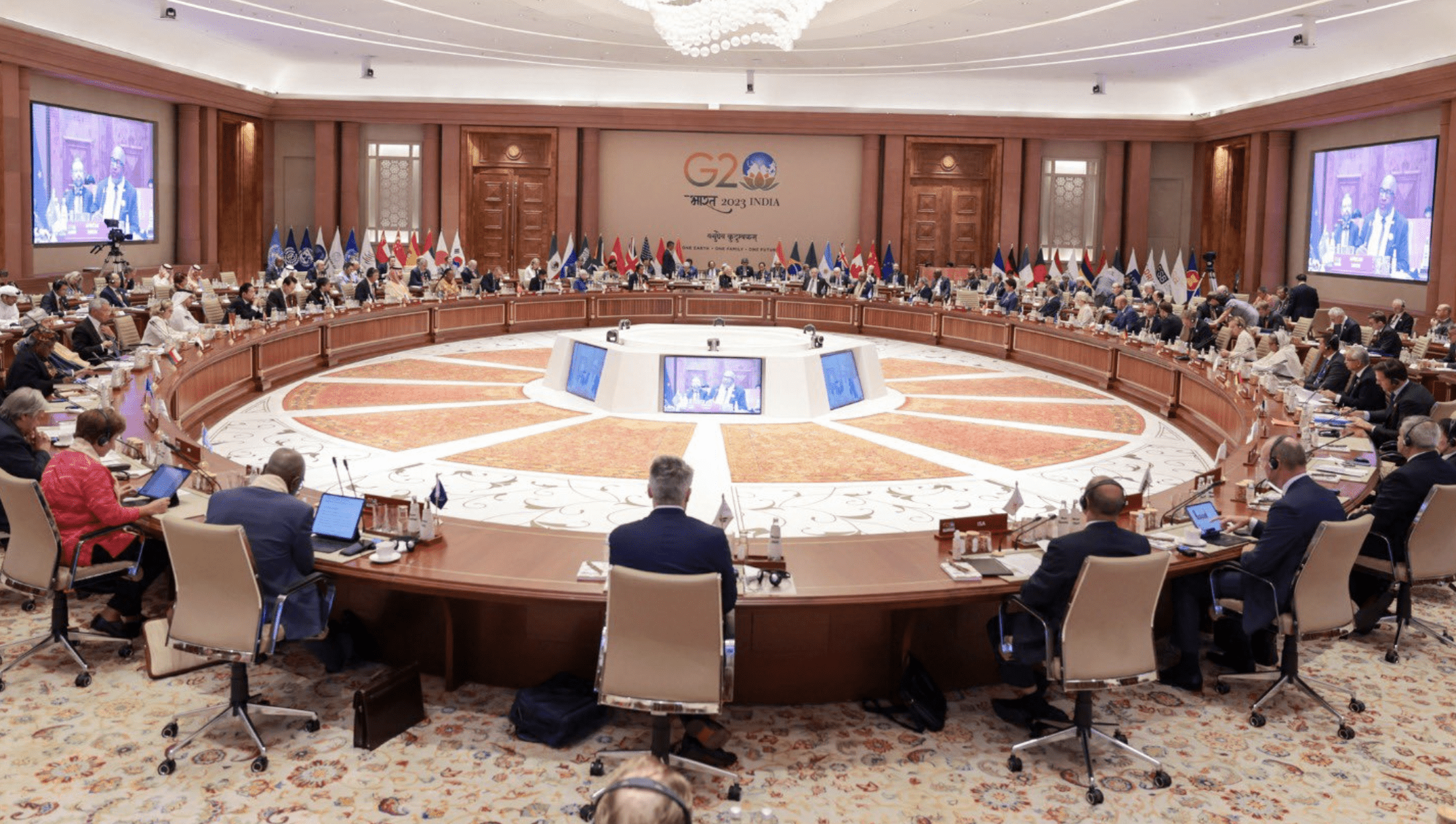

The G20 Leaders’ Summit in New Delhi/@G20org

The G20 Leaders’ Summit in New Delhi/@G20org

Colin Robertson

September 12, 2023

The G20 leaders are a ‘disparate’ bunch – dictators, and democrats – but it is the premier forum for international economic cooperation. They met this past weekend in New Delhi around the theme of “One Earth, One Family, One Future”.

Despite their differences and with Indian prime minister Narendra Modi in the chair, they achieved a consensus declaration that addresses Ukraine, climate mitigation, food and energy security, as well as debt relief. In recognition of the growing weight of the Global South, the African Union, representing the 55 nations of the second most populous continent, joins the group.

On Ukraine, while it failed to explicitly condemn the Russian invasion as G20 leaders did in last November’s Bali communiqué, the intent is clear with the call for states to abide by the UN Charter, refrain from using force for territorial acquisition, cease attacks on civilians and infrastructure, declaring “inadmissible” the threat or use of nuclear weapons and calling for restoration of the Black Sea Initiative around shipping of food and fertilizer “to meet the demand in developing and least developed countries, particularly those in Africa.”

Looking to the climate change conference (COP28) in Dubai this December, G20 leaders agreed to “triple renewable energy capacity globally” and pledged preferential financing to help developing countries transition to lower emissions.The G20 accounts for over 75 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. A Global Biofuels Alliance will include India, USA, Argentina, Brazil, Italy, Mauritius, and the UAE.

In other institution-building, India, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, France, Germany, Italy, and the European Union pledged to work together in developing the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor – a new ‘spice route’ designed to increase their connectivity. The US, India and Gulf countries also announced a ‘historic’ new railways and port corridor to link the regions. These new initiatives will both compete with and complement the Chinese-driven Silk Road and Maritime Belt Initiative. These initiatives remind us again that economic weight and growth continues to shift to the Indo-Pacific.

Leaders agreed to collectively mobilize more concessional finance to boost the World Bank’s capacity to support low- and middle-income countries. Rising interest rates have escalated debt financing. The World Bank calculates that the world’s poorest nations face annual debt servicing of over $60 billion to bilateral creditors, escalating the risk of defaults. Two-thirds of this debt is owed to China.

Recognizing the critical role of digital infrastructure, India will build and maintain a Global Digital Public Infrastructure Repository. In a joint statement on the eve of the G20, the World Bank and IMF noted that nearly 3 billion people remained offline, the vast majority of whom live in developing countries.

For Justin Trudeau, the G20 was part of travel to Jakarta for the ASEAN summit, to Singapore to promote economic ties, and then to New Delhi, all intended to underline Canada’s increased engagement with the Indo-Pacific region.

At the G20, Trudeau tweeted that he’d pressed for “greater ambition”on climate change, gender equality, global health and inclusive growth while advocating for “continued support for Ukraine”. He committed over $100 million for programs supporting climate mitigation and food aid.

But, as with his last trip to India (2018), it was not without controversy. Trudeau’s contentious meeting with host Narendra Modi is another reminder of the twin perils of preachiness and diaspora politics. Meanwhile, the efforts to secure a closer Canada-India economic partnership, a key objective of the new Indo-Pacific strategy, are paused. Our high commissioner and his team will have to pick up the pieces.

A more successful Indo-Pacific policy initiative were the exercises, coincidental with the prime minister’s travels, involving HMCS Ottawa, HMCS Vancouver and MV Asterix with the Japanese navy and then the transit of HMCS Ottawa with American and Japanese allies through the East China Sea. Ottawa’s encounters with Chinese warships remind us that for Canada to make headway on our economic objectives, those living in the Indo-Pacific need to see that we are equally invested in their regional security.

This is what multilateralism is all about, and while giving everyone a seat can be tiresome, for a middle power like Canada it means that with ideas and diplomatic skill, we can make a difference.

Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping were G20 no-shows. Putin faces potential extradition because of the International Criminal Court war crimes warrant so he was represented by Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov.

Why Xi did not attend is unclear: was he sick, subsumed by domestic problems, or was it to snub Modi over border and other disputes? Or does he think the G20 is too ‘Western’? Xi has made few international trips: to Samarkand for the Chinese-inspired Shanghai Cooperation Organization last September, to Moscow to see Putin in March, and to Johannesburg for the BRICS in August. There, he drove the effort to expand BRICS membership of emerging economies to include Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Some see the expanding BRICS and Shanghai Cooperation Organization as rivals to the western inspired G7 and G20.

The G20 is the brainchild of then-Canadian finance minister and later prime minister, Paul Martin, and then-US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers. They recognized, in the wake of financial crisis in emerging economies (Mexico in 1994, Asia in 1997, Russia in 1998) that with globalization and the growth of the emerging economies, the G7 was inadequate to the task of global financial crisis response.

The G20 began in 1999 as a meeting of finance ministers from the G7 – Canada, USA, UK, France, Germany, Italy Japan – as well as Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Russia, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Australia, South Korea, Indonesia, India, and the European Union. They are joined by the heads of the United Nations, IMF, World Bank and World Trade Organization.

The G20 was raised to the leaders’ level in 2008 to deal with the Great Recession. The next year it declared itself the primary venue for international economic and financial cooperation representing 80 per cent of world GDP, 75 per cent of global trade, and 60 per cent of the world’s population.. It has morphed into year-long series of meetings that now involve business and civil society, culminating in the annual summits.

Given the numbers and many languages involved, the formal plenaries tend to be a series of tedious set-speeches. The real work takes place at the prior sessions involving ministers, sherpas and officials and then, after the conference begins, in the behind-the-scene meetings and corridor pull-asides.

Going into this year’s summit there was no agreement on the leaders’ communiqué given the divisions on Ukraine. The Indian officials shepherding the process say the final negotiations involved over 200 hours of meetings and 15 different drafts before agreement on the nearly 15,000-word Joint Declaration was achieved.

For Canada, multilateralism is an article of faith and a cornerstone of our foreign policy. We see it as the means by which nations can preserve peace, create prosperity and solve global problems. At a time of rising economic and geopolitical tensions, the world faces major transformational challenges and increasingly frequent shocks. Figuring this out depends on collective action by all nations.

This is what multilateralism is all about, and while giving everyone a seat can be tiresome, for a middle power like Canada it means that with ideas and diplomatic skill, we can make a difference. But making a difference requires investments in diplomacy, defence and development something our current and recent governments seem to have forgotten. That Trudeau’s Canadian Forces plane, originally commissioned in the 1990s, suffered from mechanical problems delaying his departure from Delhi can be seen as a reflection of years of underinvestment by his and previous governments in the readiness of our Forces.

Multilateralism comprises different shapes, forms and operating systems. If the G7 is like a cabinet, the G20 is more of a caucus, and the UN General Assembly a cacophony. There is a tendency to portray the various groupings as exclusionary or adversarial. They can be. In that sense, they reflect global realities, especially in this era of great power competition. But mostly, they are about identifying solutions and taking collective action to our shared problems, recognizing the realities of ‘One Earth, One Family, One Future.’

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a fellow and host of the Global Exchange podcast with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.