What a Difference a Crisis Makes: How Canadians are Uniting in a Pandemic

Before the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic began to drastically alter the daily lives of Canadians, including with the behaviour modifier of mortal fear, the country was growing increasingly divided over energy, social issues and partisan bickering. The pandemic and Canada’s response to it have moved Canadians to transcend those differences in a wartime spirit of unity that has registered in—among other places—polling on how we’re feeling about our leaders.

Shachi Kurl

It has taken the worst crisis since the Second World War for Canadians to rediscover that their leaders, governments, and institutions and even each other, perhaps, aren’t so bad after all.

In such circumstances, it is perhaps useful to reflect on the issues over which this nation had been pulling itself apart, and the corresponding fears about damage to national unity the existed before the pandemic hit.

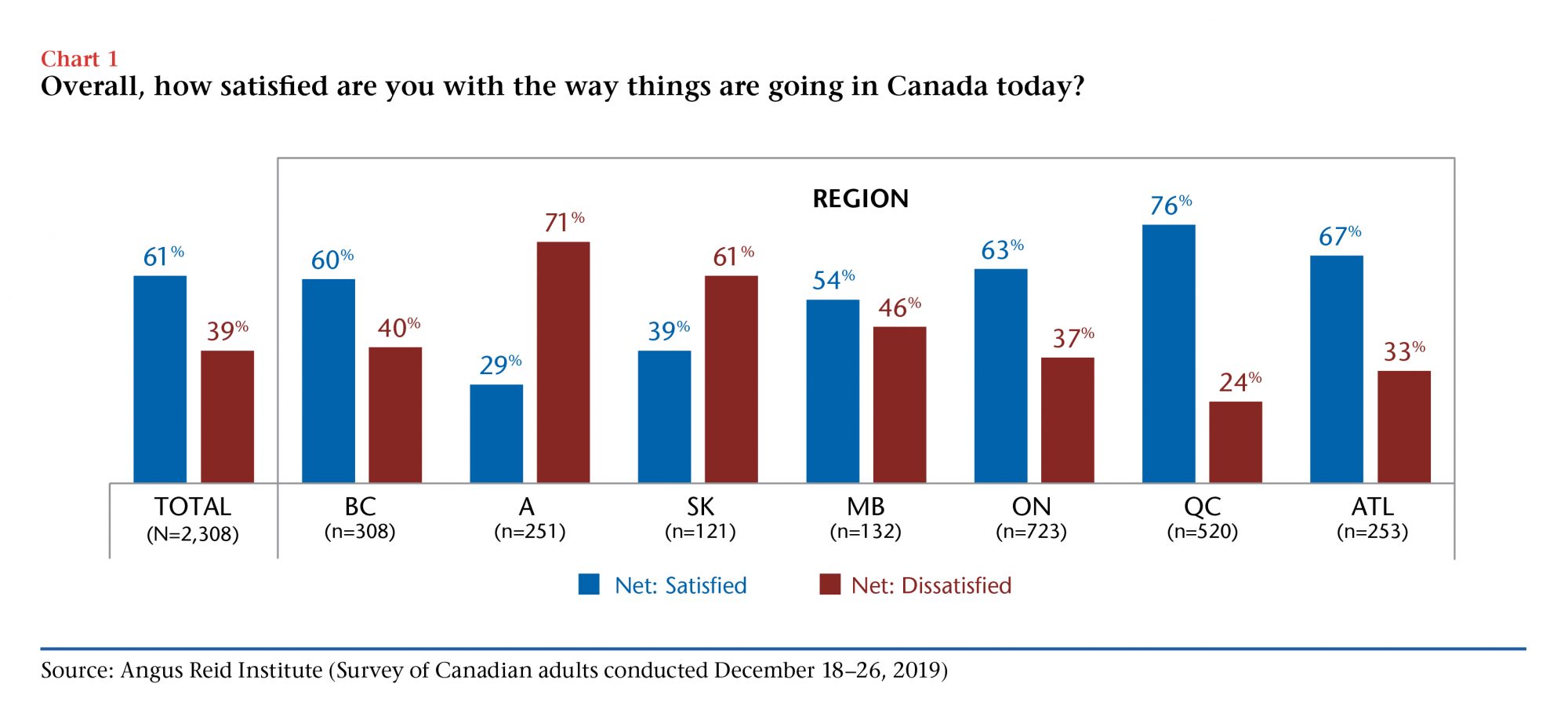

Some of those issues centered on the ongoing left versus right, economy versus environment, east versus west tug-of-war over pipeline and climate policy files. Anger over equalization, carbon pricing, pipelines and jurisdictional fights over who should have the final say on major energy projects led the Angus Reid Institute to publish a public opinion study in January, 2019, headlined “Fractured Federation”, revealing that those in Alberta, more than any other province, felt they were giving more than they got from being part of the country. Things were no better a year later, in early 2020, when 71 percent of Albertans said they were dissatisfied with the way things were going in Canada.

Some of those issues centered on the ongoing left versus right, economy versus environment, east versus west tug-of-war over pipeline and climate policy files. Anger over equalization, carbon pricing, pipelines and jurisdictional fights over who should have the final say on major energy projects led the Angus Reid Institute to publish a public opinion study in January, 2019, headlined “Fractured Federation”, revealing that those in Alberta, more than any other province, felt they were giving more than they got from being part of the country. Things were no better a year later, in early 2020, when 71 percent of Albertans said they were dissatisfied with the way things were going in Canada.

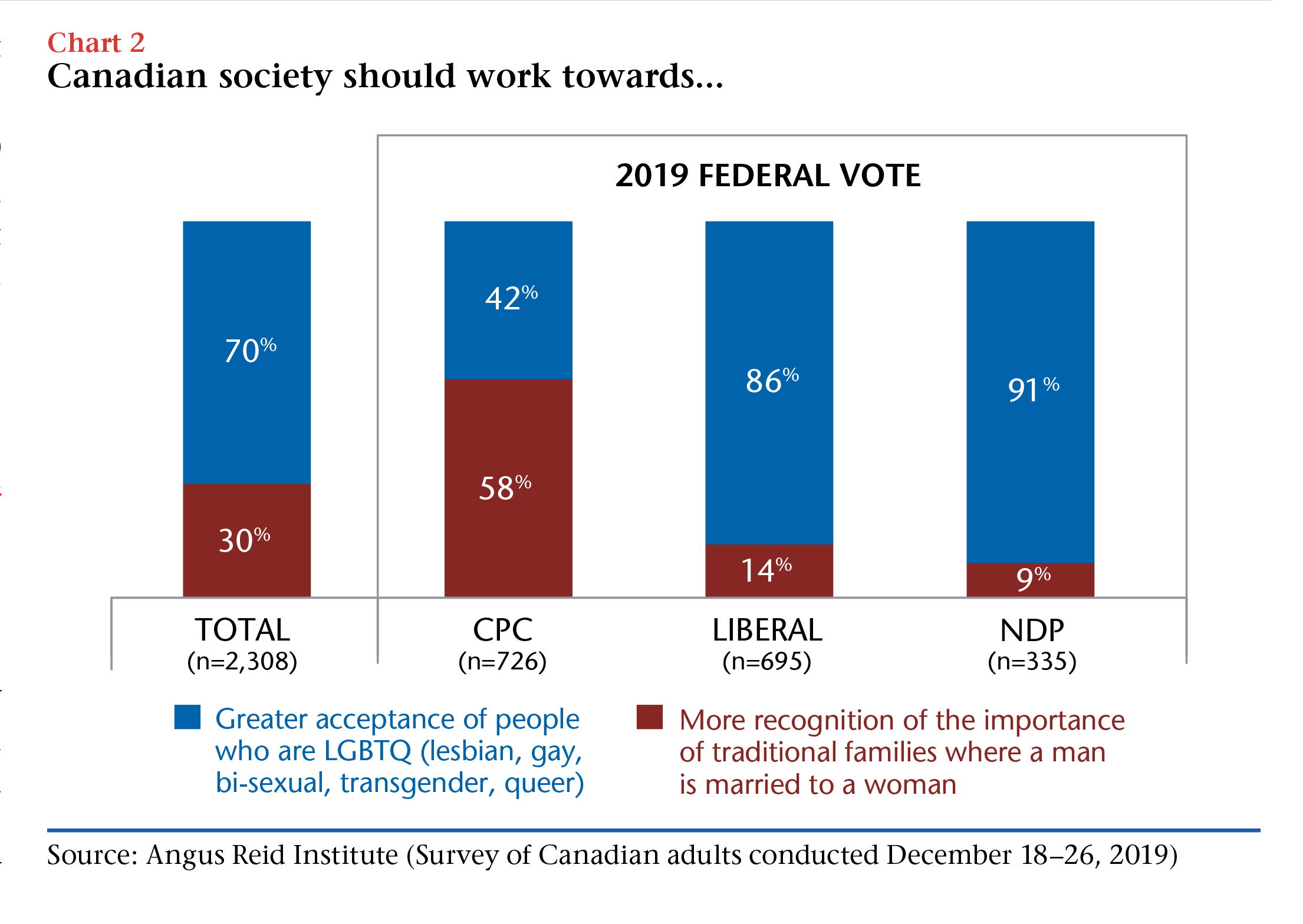

Some of those issues had centered on social values. It was the cleavage on which the 2019 election would hinge, a city-versus-rural, young-versus-older, secular-versus-religious (and once more, left-versus-right) tug-of-war over issues such as abortion, gay pride and transgender rights. Parties on the left of the political spectrum moved to a “take no prisoners” stance on abortion rights (an issue that remains divisive in this country) while the Conservative party took an equally hard-line stance on LGBTQ2 issues, a topic over which Canadians find more consensus, except among the centre right.

The result: an election outcome closer than any other in living memory, one in which support for the two “top” parties—the Liberals and Conservatives—was lukewarm: in the low 30-percent range for both.

Political watchers opined that 2020 would be the year in which national unity would truly be put to the test against the backdrop of electorates in a mood to reject the usual political suspects.

But then, the novel coronavirus came.

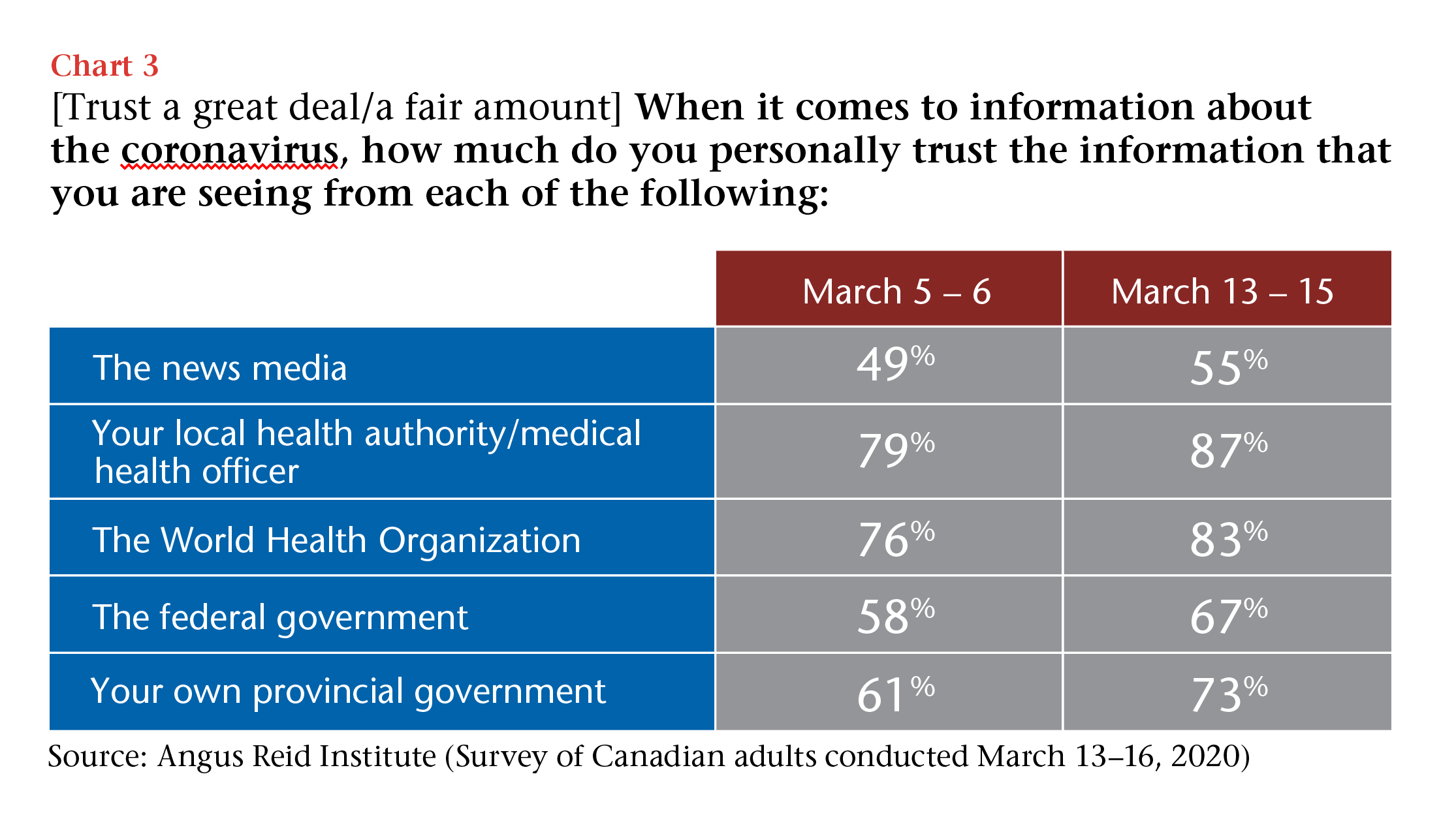

At first, the COVID-19 coronavirus was seen as a foreign problem. One affecting people on the other side of the world, where domestic cases were mostly associated with those who had travelled overseas. In early March, skepticism that surfaced in our polling over the seriousness and risk of the threat of a Canadian outbreak was driven at least in part by political partisanship, as well as diminished trust—especially among Conservatives—in government and mainstream media.

Two weeks later however, life as we knew it had changed. The NHL had abruptly benched its own season. Major retailers were closing their doors (only for a couple of weeks, we thought). Schools first extended spring break, then closed physical classrooms indefinitely. Many Canadians lost their jobs. Many traded business attire for pajama pants. A national debate began on what constituted an “essential” outing.

Two weeks later however, life as we knew it had changed. The NHL had abruptly benched its own season. Major retailers were closing their doors (only for a couple of weeks, we thought). Schools first extended spring break, then closed physical classrooms indefinitely. Many Canadians lost their jobs. Many traded business attire for pajama pants. A national debate began on what constituted an “essential” outing.

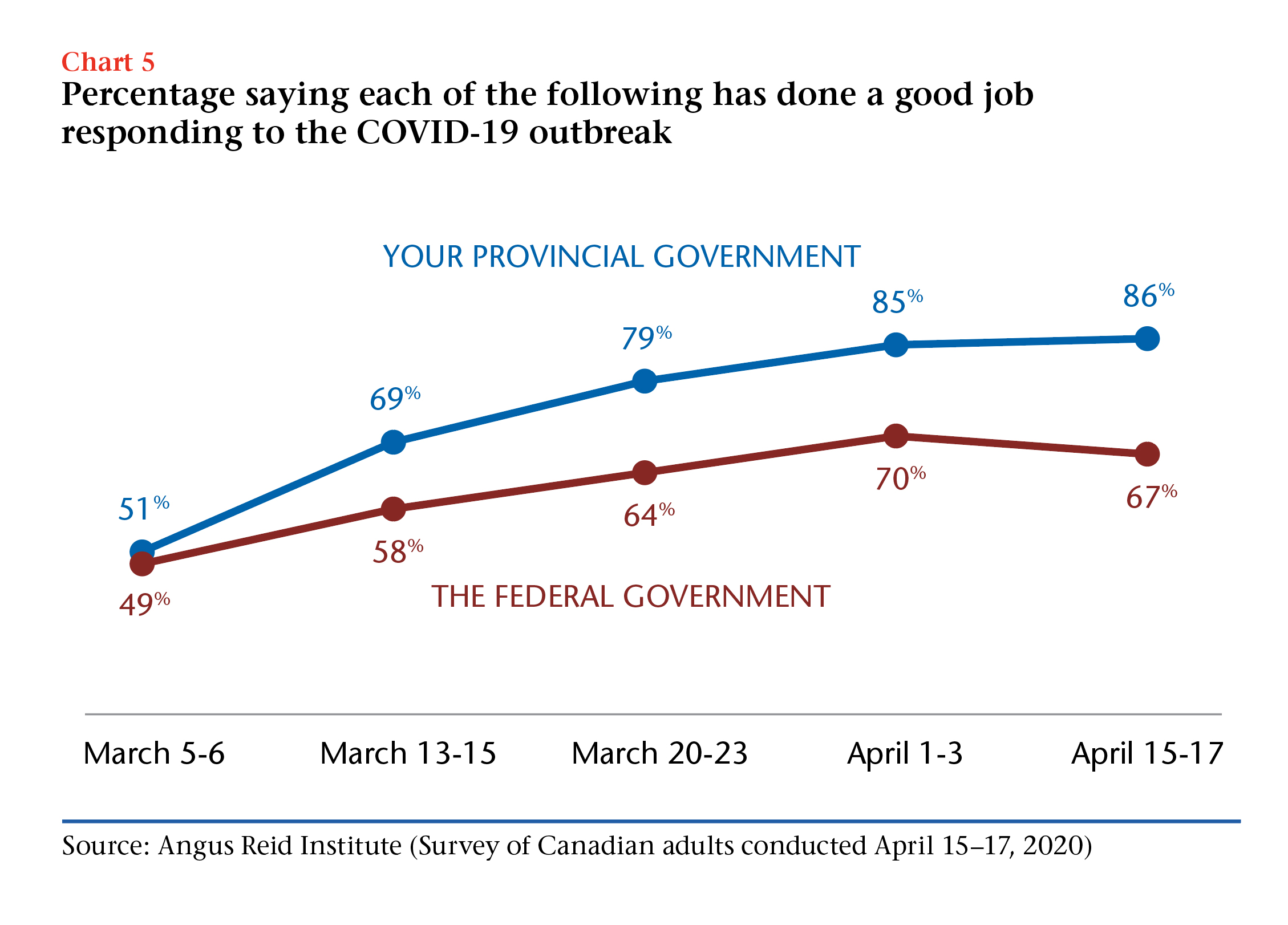

Against this backdrop, a nation that had increasingly come to view politicians with cynicism while rejecting expert knowledge in favour of memes they’d seen on social media did something remarkable: it turned to these same leaders for guidance, and trusted in what they were being told:

More explicitly, people reacted positively to the combination of reassurance and action as Canada’s provincial and federal governments dealt with the dual crises of trying to curb the deadliest health threat to darken our communities since the flu pandemic of 1918, while propping up the millions of households affected by an economy in sudden freefall.

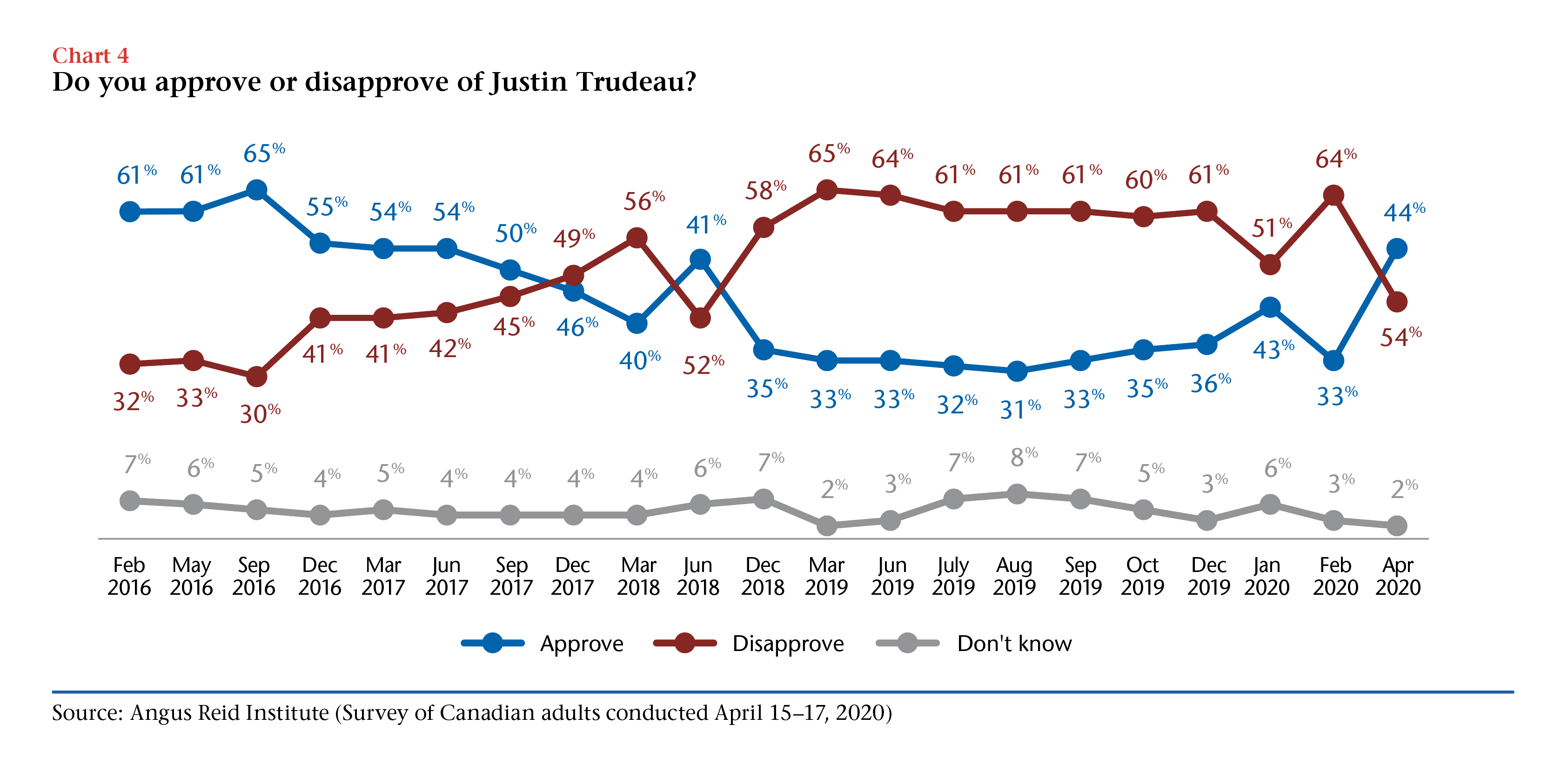

As for Justin Trudeau, the prime minister whose personal approval had been mired at an anemic 30-ish percent for more than a year? That rating jumped 21 points as Canadians (even Conservative voters) offered support for his handling of the crisis. It could be easy to dismiss such findings, to suggest they are the result of a numbed population too busy grappling with all that’s happened to focus on or adequately scrutinize the ways in which their leaders have performed.

As for Justin Trudeau, the prime minister whose personal approval had been mired at an anemic 30-ish percent for more than a year? That rating jumped 21 points as Canadians (even Conservative voters) offered support for his handling of the crisis. It could be easy to dismiss such findings, to suggest they are the result of a numbed population too busy grappling with all that’s happened to focus on or adequately scrutinize the ways in which their leaders have performed.

But that would assume the collective Canadian nose for propaganda had been temporarily disabled, a symptom if not of the coronavirus itself, then all the suffering and uncertainty it has wrought. Indeed, even if our leaders haven’t been getting it exactly right all the time—and they haven’t—the general perception appears to be that their actions haven’t been making things worse.

But that would assume the collective Canadian nose for propaganda had been temporarily disabled, a symptom if not of the coronavirus itself, then all the suffering and uncertainty it has wrought. Indeed, even if our leaders haven’t been getting it exactly right all the time—and they haven’t—the general perception appears to be that their actions haven’t been making things worse.

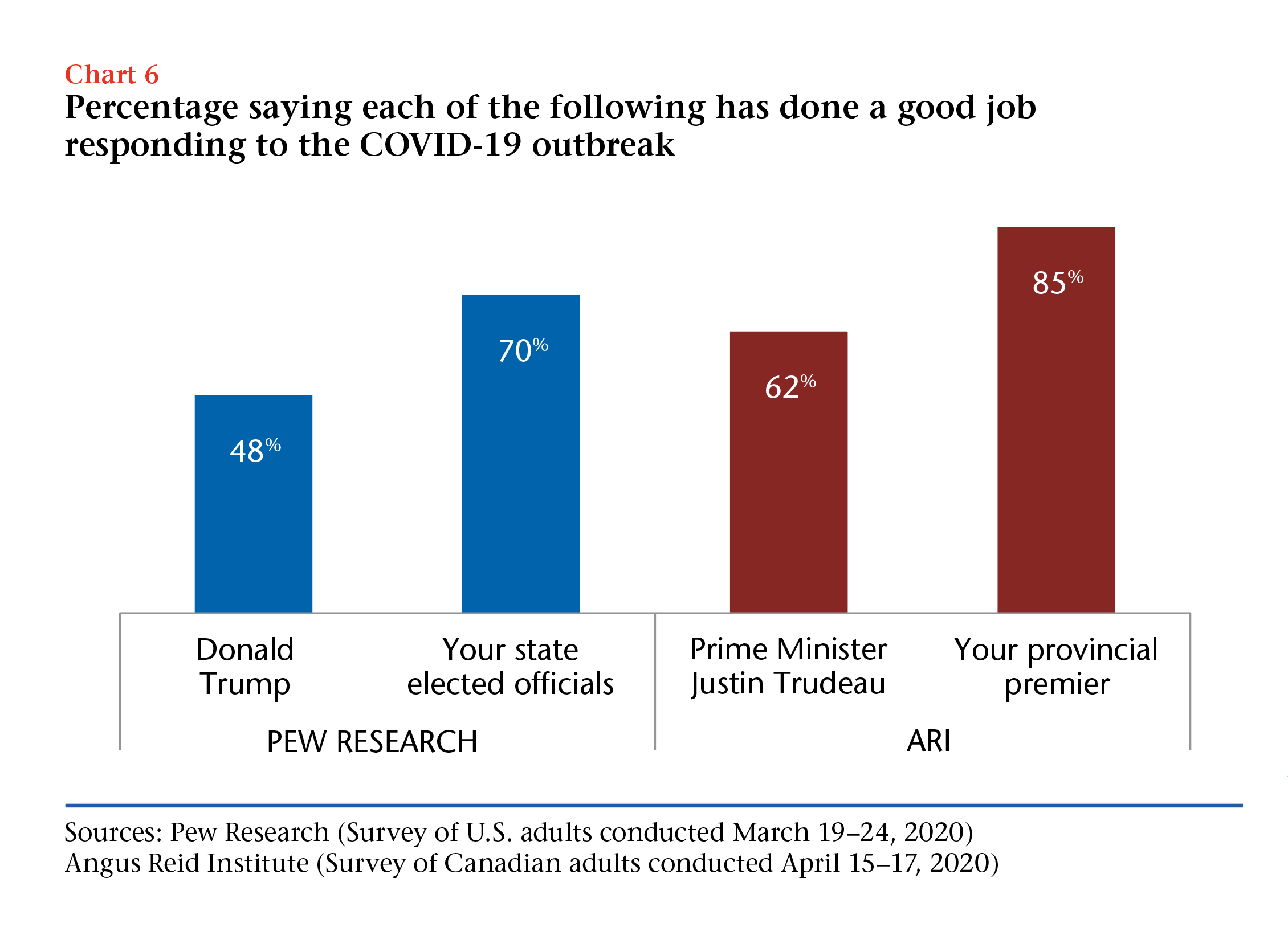

Contrast this with the way Americans feel about how their president and state leaders have tackled the COVID-19 crisis:

After the October election, so tender were federal-provincial relations that Prime Minister Trudeau eschewed a first ministers meeting in favour of one-on-ones with the premiers. But the issues that made those relationships shaky have been put aside to fight this disaster with a united front. There are no daily press conferences where premiers and the PM openly antagonize one another. There is instead an attempt—even in moments of disagreement—to keep the conversations civil.

The outstanding question is the extent to which this spirit of collective co-operation will last. A return to “normal”—or at least a path to recovery—in our health and economic lives will also bring with it a return of national policy issues that never really went away, but merely fell to the bottom of our priority lists.

Will Canada emerge from this crisis a gentler, more circumspect nation? Will we decide that the issues that felt so divisively unsolvable weren’t so impossible after all? It would not be the first time that epic tragedy and suffering had produced positive change and innovation. While we can’t predict the future, we’ll be measuring those outcomes as Canadians live through them.

Contributing Writer Shachi Kurl is Executive Director of the Angus Reid Institute, a national not-for-profit research foundation based in Vancouver.