‘Victory City’: Salman Rushdie, Alive and Kicking

PRH

By Salman Rushdie

Penguin Random House/February, 2023

Reviewed by Bob Rae

March 26, 2023

Reading a new book by Salman Rushdie is always quite the experience. No living writer can match his command of the language, his mastery of narrative and storytelling, the full extent of his imagination. He is like the maestro of an orchestra at the height of his talents — at one moment the strings, then the trumpets, then the melody returns with great crescendos, cue the drums for emphasis…he can make you laugh, cringe and weep all in a single sitting. Passages are read again and again, sometimes out loud to get the full force of his imagination, his humour and his virtuosity.

Reading this new book by Salman Rushdie is also a celebration of resilience — of both the protagonist and the author.

This is a novel of India, but above all it is a story about the power of love, creativity, statecraft, good and evil, violence and peace, life and death — a story about eternal themes, brilliantly told. The heroine of the book is Pampa Kampana, a woman who lives for centuries, and whose long life allows her to witness the transformation of her country. Armies come and go, children are born and die, lovers emerge and disappear, the only thing that is constant and unchanging is Pampa Kampana’s spirit and will in the face of much cruelty and misplaced cunning.

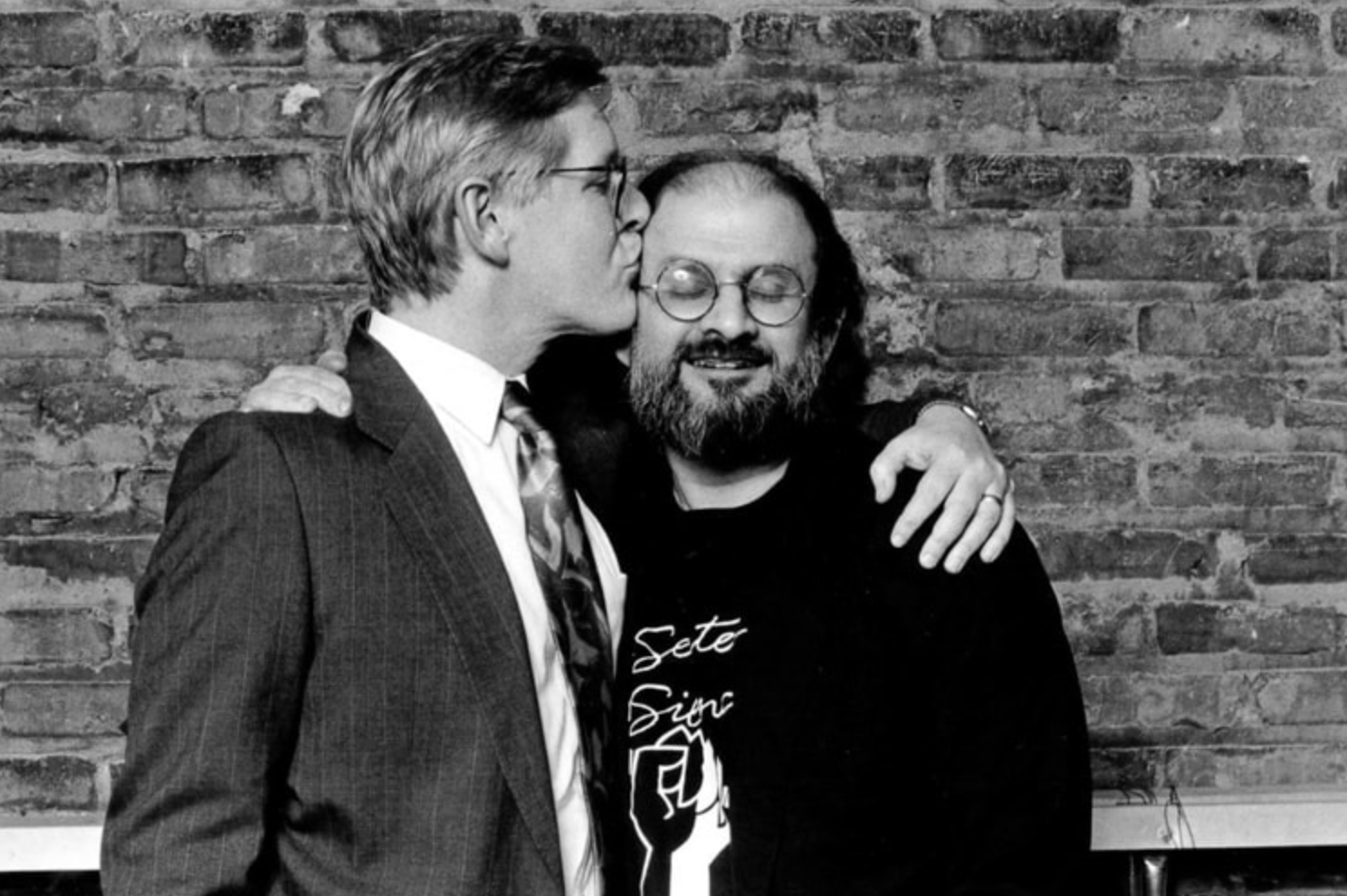

Thirty years ago, I had the chance to meet Salman Rushdie for the first time. His novels, essays and children’s stories were already well known to me, but he had suddenly become famous — in some circles wrongly infamous — because of the 1989 issuance of a fatwa on his life; an order from Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini that he should be hunted down and killed because of the alleged blasphemy of his novel The Satanic Verses. The novel, said the Ayatollah, was, “a text written, edited, and published against Islam, the Prophet of Islam, and the Qu’ran”, and that Rushdie, “along with all the editors and publishers aware of its contents,” were thereby “condemned to death”. There was a $1 million bounty on his head.

At the time, in 1992, I was Premier of Ontario. I was asked by PEN Canada whether I could help Rushdie come to Toronto and appear with him publicly at a PEN benefit. Rushdie was then living under police protection in London, moving from house to house. The threat on his life was very real — his Japanese translator, Hitoshi Igarashi, was murdered. His books were banned by Muslim countries and many booksellers elsewhere removed his books from their shelves. The moral debate between those who supported him and those who shunned him exposed a facility with capitulating to tyranny among certain intellectual and political elites that confounds to this day. I made the decision to do what I could to help his travel (airlines would not accept him as a passenger) and met him privately on the weekend before his Sunday evening surprise appearance at the Toronto event.

Public display of affection: The 1992 Kiss that defied a fatwa/PEN Canada

Public display of affection: The 1992 Kiss that defied a fatwa/PEN Canada

I was the first head of government to greet Salman Rushdie publicly, and I am glad I had the chance to do so — the assault on freedom of speech, and Rushdie’s personal safety, was an affront to everything I believed in. Any reading of Satanic Verses would show that it was not “anti-Muslim” any more than Elmer Gantry is anti-Christian — the fanatics who cloaked themselves in religious piety were self-interested political authoritarians (just as they are today). To me, it was a question of one man’s life but also of the larger human rights principle for which he had become an involuntary avatar and test case. Some decisions aren’t about bravery because they’re really not a choice at all.

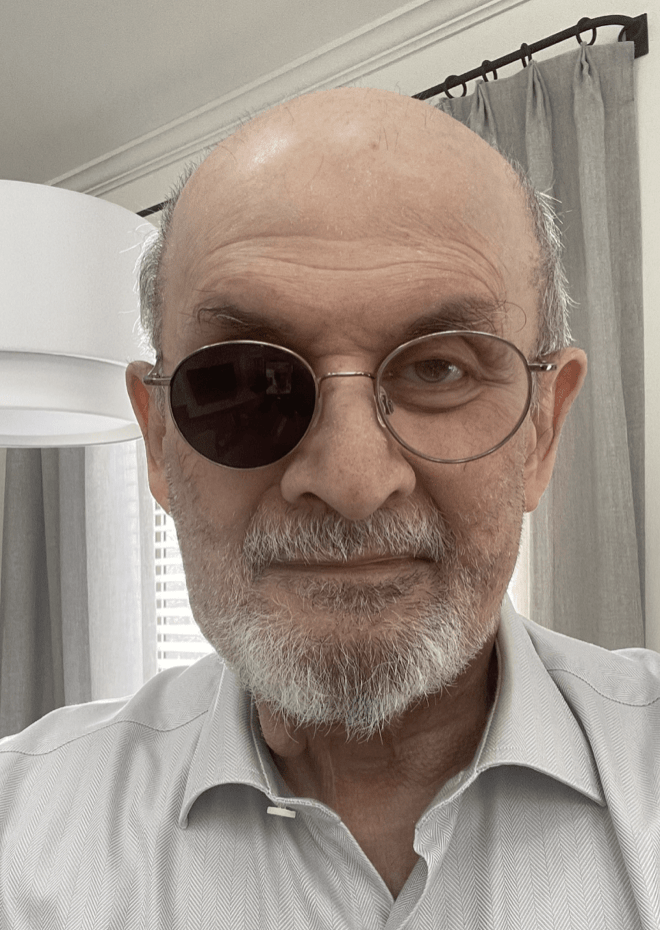

Last summer, 30 after our first meeting, Rushdie, now living in New York, was viciously attacked while at a public reading at the annual Upstate writer’s festival in Chautauqua. He came within a few millimetres of losing his life — he has survived multiple stab wounds, lost the use of his right eye and sustained nerve damage in his left hand that makes typing difficult. But the depth of his commitment to freedom of speech remains undeterred. “Now that I’ve almost died, everybody loves me,” Rushdie told The New Yorker’s David Remnick in his first post-recovery interview. “That was my mistake, back then. Not only did I live but I tried to live well. Bad mistake. Get fifteen stab wounds, much better.” His courage and humour are both a form of defiance and a living tribute to his determination to remain true to his own imagination and creativity at a time when the imagination and creativity of tyrants are rewriting the precedents of barbarism daily.

Victory City is appropriately titled because out of this tale about medieval India — a tale embroidered with the fantastic, the magical, the bombastic, the outlandish — comes the triumph of the human spirit in the face of tyranny and darkness. Pampa Kampana’s victory is Salman Rushdie’s triumph. Even half-blinded, he is undaunted. He is not interested in self-censorship or saving people’s feelings. He is determined to tell the truth as he sees it, and it is a truth that is never polemical, or strictly political — it is universal. There is poetry and eloquence. In Pampa Kampana, Rushdie has given us a heroine for our times — worldly wise, feisty, courageous beyond belief, and capable of both love and grief.

From Salman Rushdie’s first post-recovery tweet in February

At the end of the Second World War, George Orwell, Arthur Koestler and Bertrand Russell joined forces to create a modern alliance of writers to fight for freedom. In their manifesto, they wrote that “It has been forgotten that without liberty there can be no security…over considerable portions of the earth not merely democracy but the last traces of legality in our sense of the word have simply vanished.” Writing in this world requires great strength of spirit in the face of all the new threats to liberty that surround us, and in this small moral universe, an attack on one writer is an attack on all. Salman Rushdie, who has carried the burden of that truth as lightly as anyone possibly could, walks as a giant among us.

Bob Rae is Canada’s permanent representative to the United Nations and a regular Policy contributor.