Twitter, for Better and Worse: The Evolution of Campaign Culture

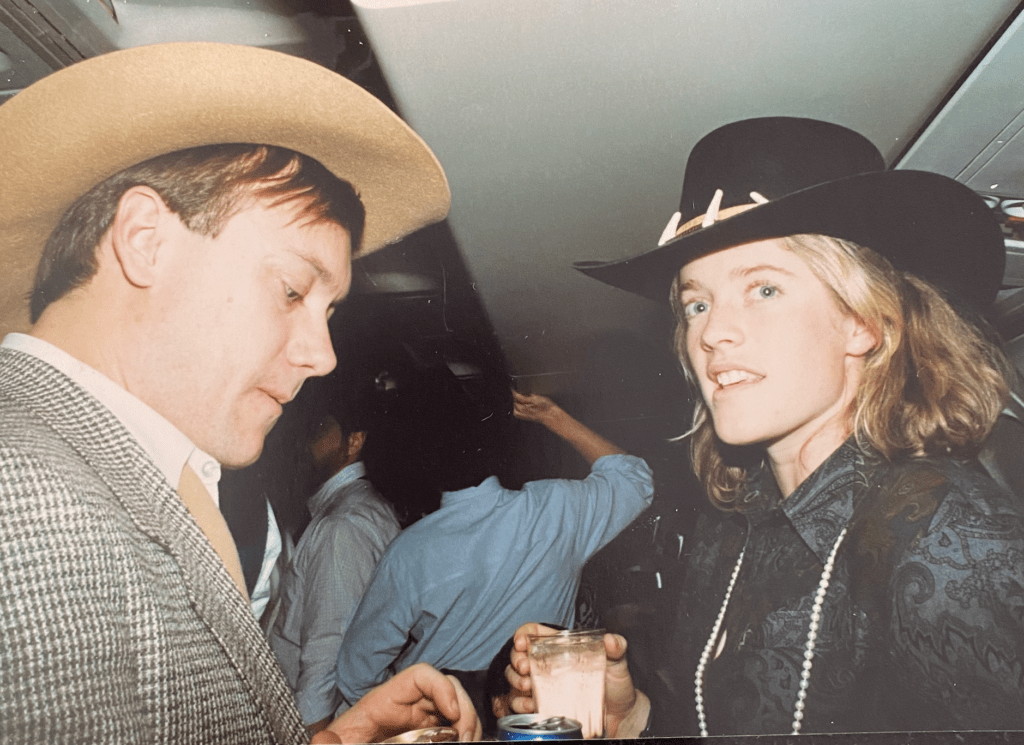

Keith Boag engaged in a meaningful policy discussion with John Turner’s daughter, Elizabeth, on the Liberal campaign plane in 1988/Photo courtesy Keith Boag

Keith Boag

September 13, 2021

Every federal election campaign provokes a round of pearl-clutching and head-shaking over just how bad retail politics have become, as though previous iterations of this exercise were marvels of civility and restraint.

Watching “Campaign 2021” has got me thinking about the great free trade election of 1988, as it’s come to be known. Free trade arguments have a long history in this country, indeed a long history around the world, and in ‘88 we were up to our toques in one. What a nasty piece of work it was: public hysteria, mobs, violence and almost unimaginable political treachery. And we ginned up all that dreadful behaviour without the aid of Twitter. Imagine.

I was in the thick of it. It was my first campaign as a CBC reporter and though there would be a half-dozen more campaigns in my future, that one still stands out as a milestone on the dismal downward spiral of our national conversation.

We call it “the free trade election” because the Canada-US trade agreement, or FTA (the historic blueprint for NAFTA and other global deals to come), negotiated by Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative government with US President Ronald Reagan’s administration, would stand or fall depending (I kid you not) on what Canadians decided at the ballot box.

The vicious tone of the campaign was predetermined by the density of the trade agreement itself. It was hard to grasp in all its complexity. For most people the particulars were too complicated and arcane for reasoned discussion. But its very opaqueness was what made it perfectly suited for a hot-headed quarrel about Canadian identity. And since Canadians were told the stakes were existential, quarrel they did.

Some lowlights from the seven-week campaign:

Mulroney and Liberal leader John Turner reduced the leaders’ debate to a toxic test of patriotism. “You’ve sold us out!” said Turner. At a luncheon speech in Ottawa, Mulroney’s normally staid finance minister, Michael Wilson, branded Turner a liar. A few days later, the retired civil servant who’d negotiated the deal also went on the record about Turner: He was worse than a liar, he was a traitor!

Placard-waving mobs on both sides of the argument surrounded the campaign buses when they rolled into towns. Fistfights broke out — I saw a bloody brawl at a Winnipeg rally — the country seemed to be coming unglued. Public opinion gyrated like never before or since — at first signalling a Conservative majority government, then a Liberal majority, and finally a Conservative majority again.

In the middle of it, CBC uncovered a spooky plot among senior operatives in the Liberal Party to replace Turner as their leader. The National’s anchor, Peter Mansbridge, broke the story, but I was the CBC man on the Liberals’ bus and they were already unhappy with my reporting, so I felt a target pinned to my back.

Imagine if social media had existed then. I would have been Twitter-mobbed — assaulted for my reporting, mocked for my hairstyle, ridiculed for my wardrobe, subjected to wild assumptions about my private life and maybe even threatened. If I were a woman, it would have been worse.

The party decided it had to do something about me. So, a campaign operative called me on a Saturday morning to invite me for a coffee and we politely talked things over. That was it. Coffee and chat.

Imagine if social media had existed then. I would have been Twitter-mobbed — assaulted for my reporting, mocked for my hairstyle, ridiculed for my wardrobe, subjected to wild assumptions about my private life and maybe even threatened. If I were a woman, it would have been worse. And the Liberal Party wouldn’t lead the attack, it wouldn’t have to: Free-lance trolls now do that kind of dirty work for all the parties. So, I feel for the young men and women on the campaign trail in this age. It can be a nasty and mucky place.

A few days ago, a reporter I follow tweeted about her exchange with Justin Trudeau after protesters threw gravel at him during a London, Ont. campaign stop. She had asked Trudeau whether he had been hit — precisely the sort of question that corresponds with the job definition of reporting. But almost immediately, she was hounded on Twitter for her questioning as though asking the PM for details isn’t a reporter’s job. I suppose nothing so quickly crushes the public appetite for sausage as watching one get made.

But here’s the thing: journalists are still better off in the Twitterverse than outside it. There is civility amid the crudeness, though perhaps not in equal proportion. Trolls notwithstanding, Twitter can be a tremendous forum for understanding, expertise and critical thinking. (140 characters is not a limit, many threads are brilliant expositions of complex concepts.)

A couple of weeks ago, when the campaign was momentarily distracted by the abortion issue (as seems to happen most elections), some user tweeted that the right to abortion was settled by the Supreme Court in 1988. That’s not true. He was immediately schooled about the true history of the issue by better-informed users and we moved on wiser for it.

How might Canadians have experienced the ‘88 election had Twitter been around? It would likely have been even nastier, but voters would almost certainly have been better informed.

In 1988, the big media players — CBC, The Globe and Mail, etc.—did their best to synthesize and present the substance of the trade agreement with special features and programming. But they never got the timing right. They did their best work before anyone cared enough about the issue to read or watch it, and by the time people cared about the issue, we told ourselves we’d already covered it.

I no longer have the stamina for a modern campaign, in which the trolling of working journalists has become part of the political culture. And it’s true that Donald Trump, because he treated all politics as theatre and all theatre as a platform for his narcissism, soiled Twitter by weaponizing it and the sludge from that experience has slopped over the border.

But the best of Twitter, because it’s always on, always working — as the brilliant New York Times media critic, the late David Carr said, Twitter is the campaign bus now — has the ability to explain, contextualize, fact-check and spread information instantly. It has everything it needs to make civic behaviour better. It is a tool, and in the best hands, it’s a hell of a tool.

Keith Boag is a former Ottawa-based chief political correspondent for CBC national news and former Washington correspondent for the network. He has covered seven federal election campaigns and four US presidential elections.