Truth and Remembrance: A Trip to the Russian Arctic

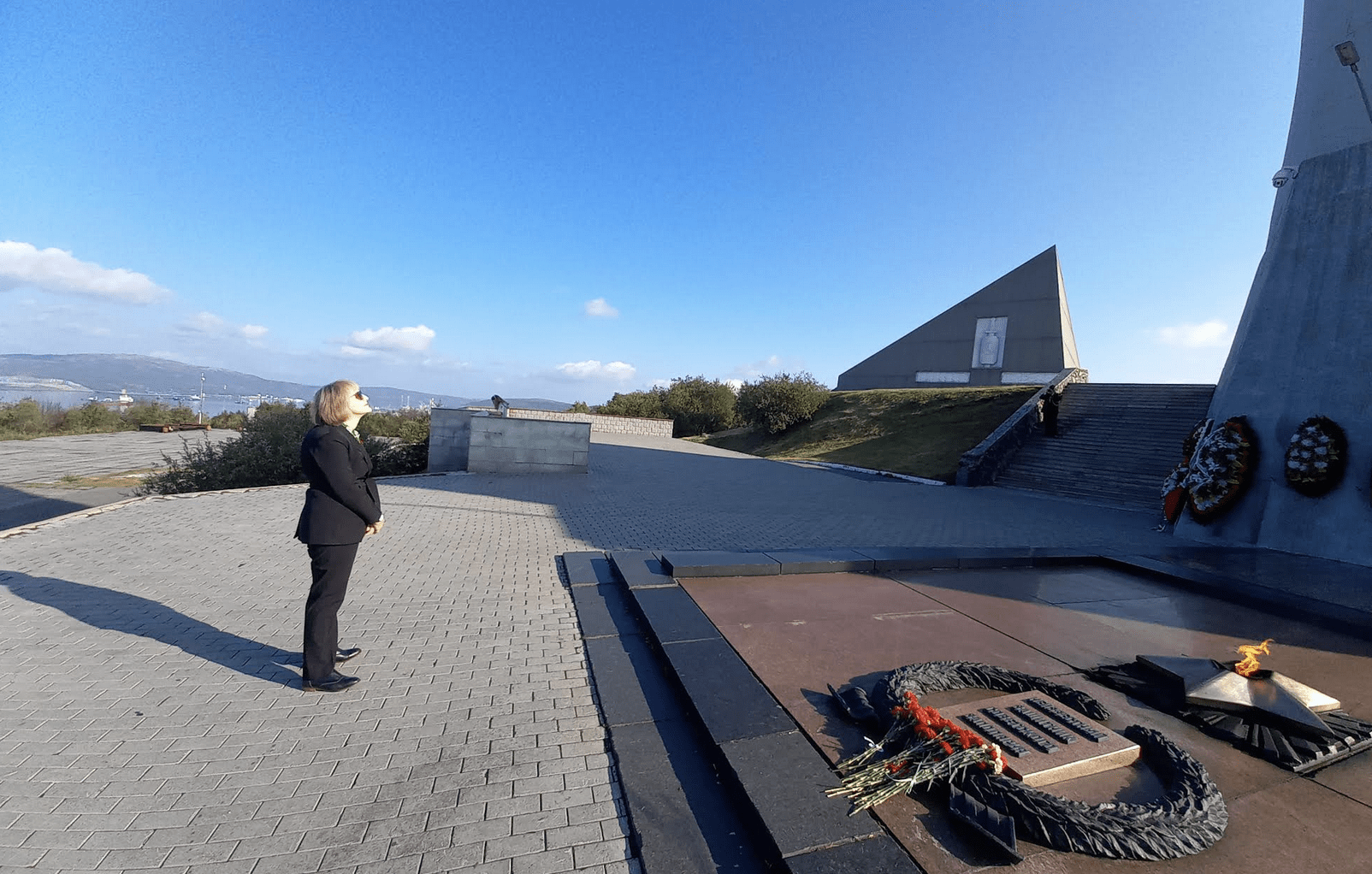

The Alyosha’ monument to the World War II defenders of the Arctic in Murmansk

The Alyosha’ monument to the World War II defenders of the Arctic in Murmansk

By Sarah Taylor

October 29, 2024

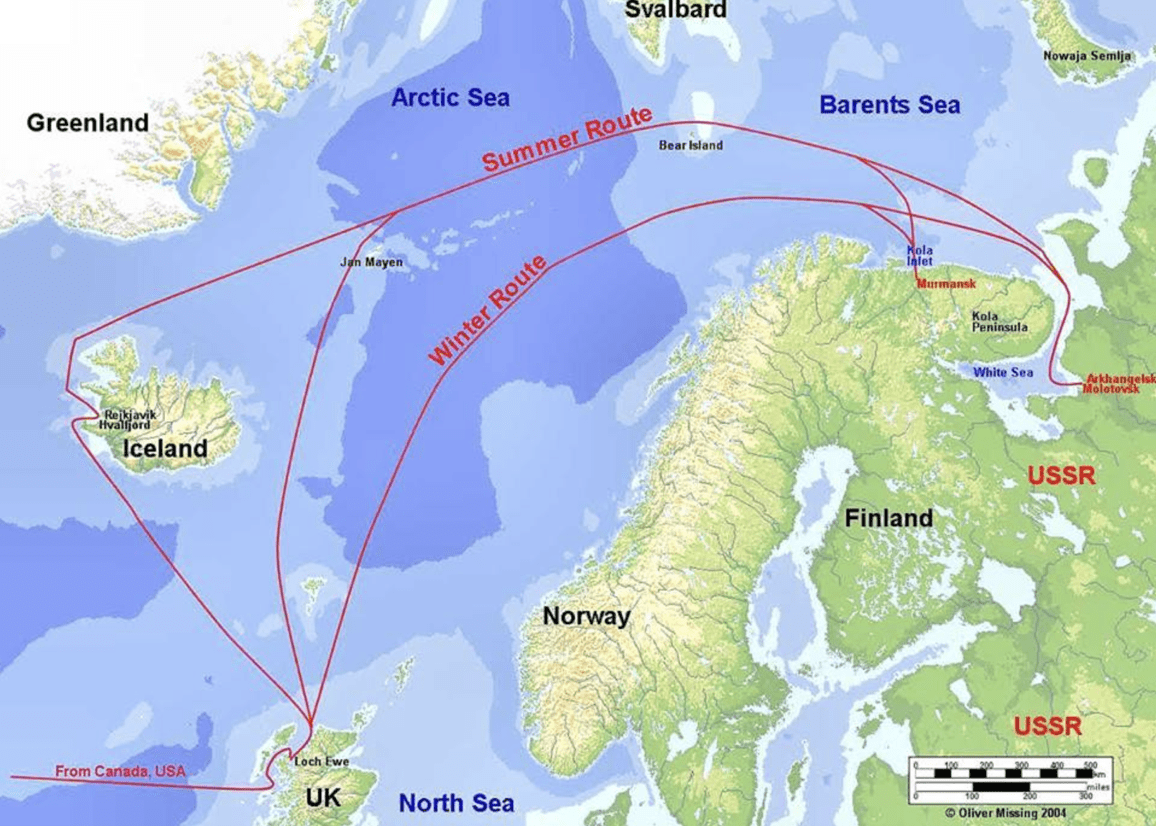

With some 270,000 people, Murmansk is by far the largest settlement north of the Arctic Circle. While it is not a beautiful city, it carries a rich history. The city exists because a rare warm current keeps its harbour free of ice year-round. This led Tsarist Russia to build a port and a railway line there in 1915 (during World War I). During World War II, it became the main port through which 41 heroic Allied Arctic Convoys supplied the USSR. Known as the Murmansk Run, that supply line was among the most harrowing and dangerous missions of World War II.

Map of the WWII ‘Murmansk Run’ supply line served by Allies, including Canada

Map of the WWII ‘Murmansk Run’ supply line served by Allies, including Canada

In August 2024, I was in Murmansk, and then in the slightly more southerly port city of Arkhangelsk, to visit the monuments to the convoys, and the graves of Canadian soldiers and seamen who died in the Russian North during both World Wars.

Murmansk’s rail lines run parallel the port, blocking the rest of the city from the shores of Kola Bay, close to the Barents Sea. Much of the city was bombed flat during World War II and then rebuilt in bleak Stalinist concrete. A closed city for many decades, its fishing and naval economy is now supplemented by tourism and plans for increased shipping via the Arctic Ocean. The skyline of this low-lying, gritty city is dominated by the hotel where we stayed – at 17 stories, the tallest structure north of the Arctic Circle – and the massive socialist realist “Alyosha” monument to the World War II defenders of the Arctic. From the hilltop beside Alyosha, you can almost see the spot 80 kilometres to the west where the invading Nazi forces were stopped from seizing the city and continuing their advance into Soviet Russia.

The Kola Peninsula where Murmansk is located has a much older history of settlement, evidenced by petroglyphs and mysterious stone spirals dotted around its shore and on its lakes and rivers. Among the early inhabitants are the Sámi, an Indigenous people also living in Norway, Sweden and Finland. Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Canada supported exchanges with the Sámi and other northern peoples, bilaterally and through the participation of the Russian Association of Indigenous People of the North in the Arctic Council. I was able to meet one local Sámi representative during my visit, but any substantive cooperation is on hold.

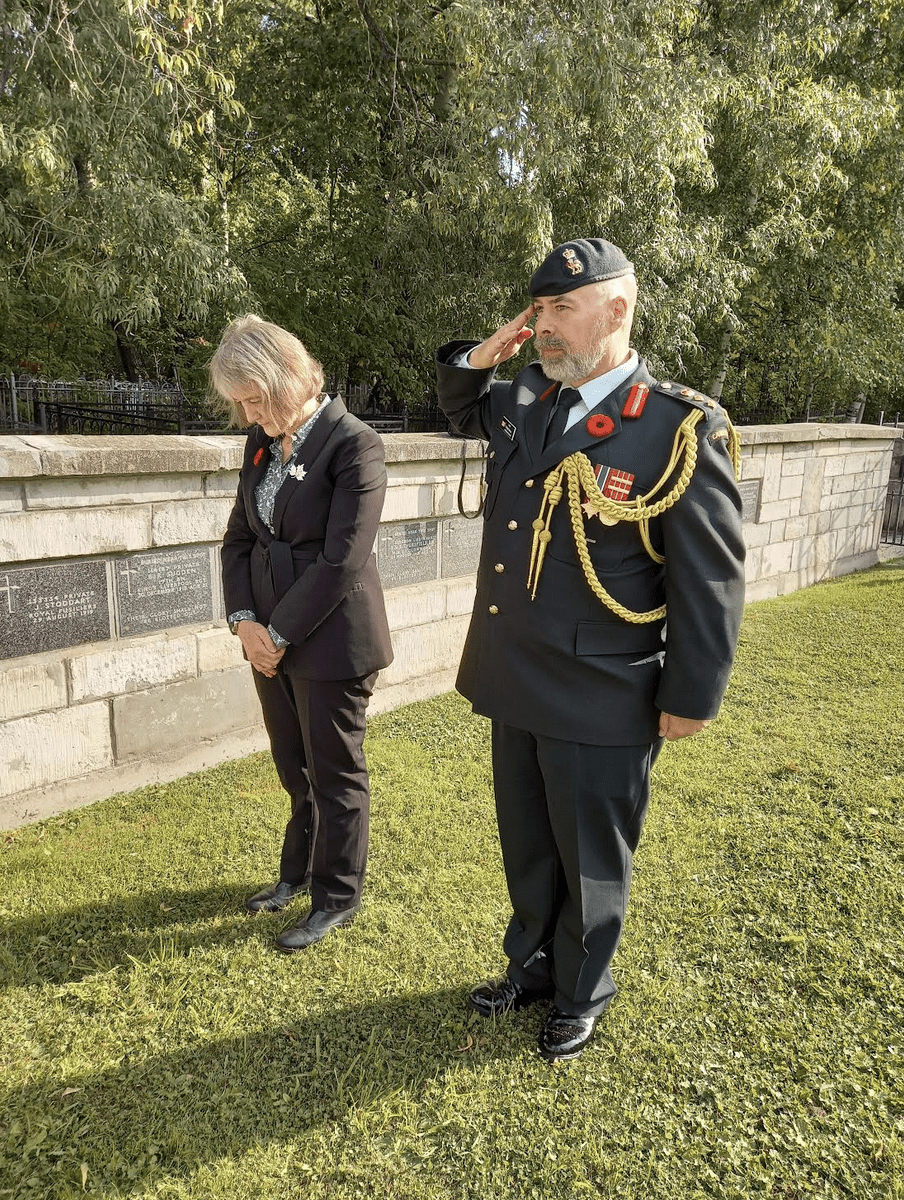

Memorial ceremony for Canadian soldiers and seamen in Arkhangelsk

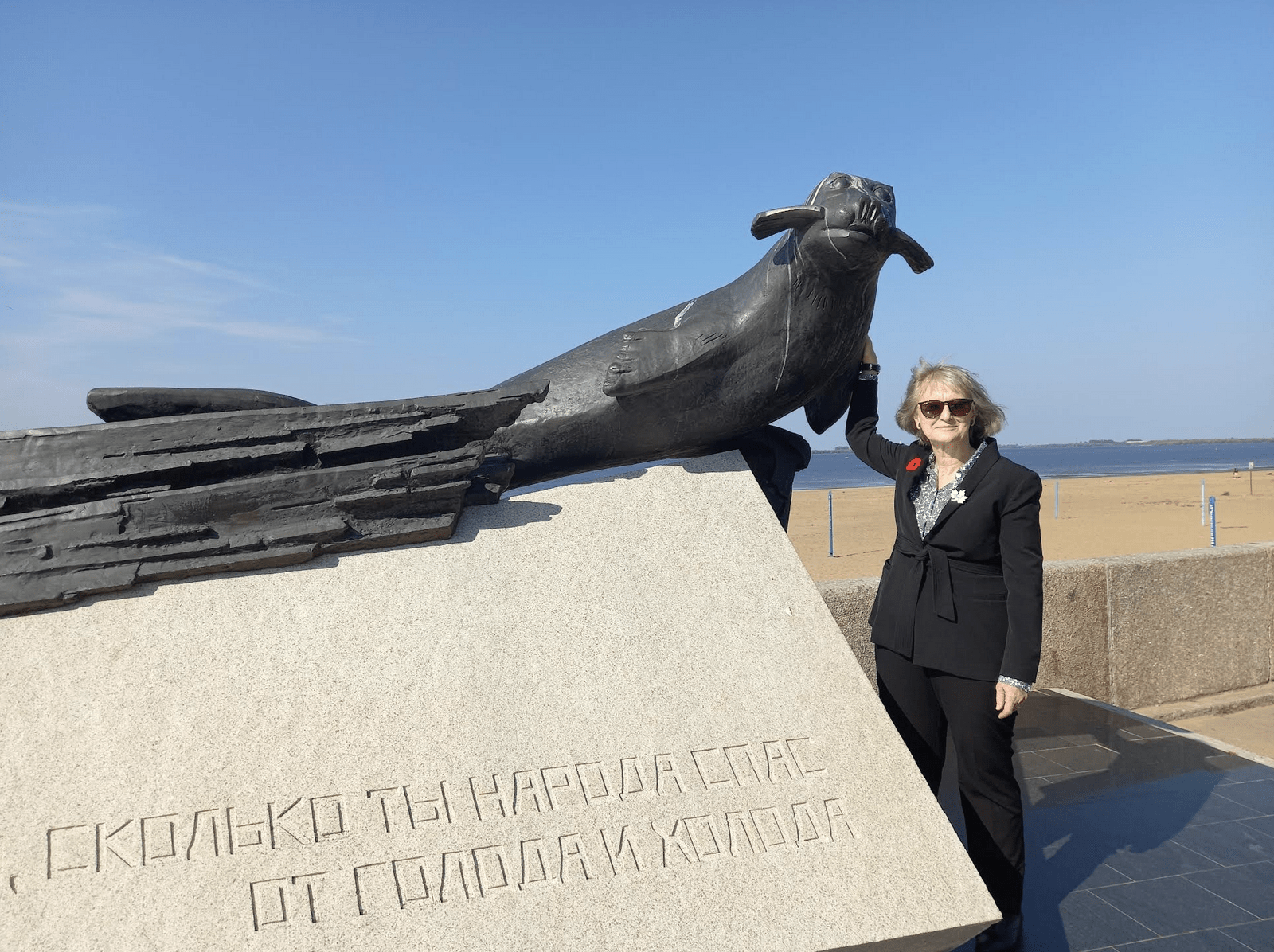

Our second stop was in Arkhangelsk, founded in 1584 and named after the Archangel Michael, with a core of charming 18th and 19th century stone and wooden buildings. Although much older than Murmansk, it is less effective as a port, since its harbour on the Northern Dvina River, just off the White Sea, freezes in winter. Despite this, it was also an important destination for the Arctic Convoys. The various World War II monuments along the waterfront commemorate not only the Convoys but also the local seal population, an important source of food during wartime deprivation. I made sure to take a selfie with the seal memorial to show my Newfoundland husband and in-laws.

With Arkhangelk’s ‘Monument to the Seal’

With Arkhangelk’s ‘Monument to the Seal’

This was not a trip simply to satisfy historic curiosity, however. Honouring Canada’s war dead buried abroad is one of the most solemn and touching duties of any Canadian diplomat. In Murmansk, I paid respects to merchant seaman Georges Auger but was unable to visit the grave of Flight Sergeant Walter Tabor within the Severmorsk naval base. In Arkhangelsk I laid flowers at the graves of Royce Dyer, Claude Lemoine, Douglas MacDougall, David Fraser, John McDonald and Frank Russell, and at memorials to Walter Conville, Cail Erikson, Stanley Wareham, and Cecil Worthington. All of them fought first in World War I, and then in support of the White Army in the Russian civil war following the 1917 Revolution. I also paid respects to the British, Australian, Polish, Commonwealth, and Soviet men and women, casualties of both World Wars, commemorated in cemeteries and memorials in these two cities. In Arkhangelsk, I was joined by the Australian ambassador, as a few Australians are also buried or commemorated in the cemetery there, far from home.

These visits are not just about remembrance, but also about truth, about setting the historical record straight. The USSR suffered horrendous losses in World War II and made great sacrifices. But the Soviet and current Russian governments have manipulated that history for political advantage. A stroll around the monuments of Moscow’s Victory Park, for example, would leave you thinking that the fight against Nazi Germany began in 1941, led by the USSR and a vaguely-defined UN coalition. Setting the record straight means re-surfacing the alliance between Stalin and Hitler from 1939 to 1941 and reminding Russians of the Allied contribution to defeating Nazi Germany.

World War II poster/Canadian War Museum

The Canadian contribution to that effort was significant. Canada’s merchant navy made more than 25,000 trips across the Atlantic during World War II; those on the treacherous Arctic route brought military equipment, medical supplies and food to the USSR. One of the amateur historians I met in Archangelsk told me his father spoke of eating bread made from Canadian wheat brought by the convoys, at a time when all food was scarce, never mind white bread. By the war’s end, Canada had the third-largest navy in the world; almost 10 per cent of the Canadian population had enlisted in the armed forces and close to 1 per cent had been wounded or killed.

The legacy of the Murmansk convoys is an important counter to two strands of current Russia propaganda: that Western countries are innately anti-Russian, and that Canada is friendly to supposed “Nazis”. It is nonsense to suggest that the government of Ukraine, or by extension its supporters, is pro-Nazi. Canada’s policy of sanctions and limited engagement toward Russia is in response to Russia’s illegal and unjustified invasion of Ukraine. There is no hidden “Russophobic” agenda at play, simply a call for Russia to respect the most basic principle of the UN Charter. It is a sad irony that a country that makes so much of its victory in what it calls the Great Patriotic War shows utter disrespect for the most precious outcome of that carnage: the international agreement that disputes between sovereign countries are no longer settled by force.

Between the Archangel Allied Cemetery and the main road lies a new section of the Arkhangelsk cemetery. It contains about 50 graves of Russian soldiers killed since 2022 in Ukraine. Billboards nearby commemorate some of these Russian “heroes”. Their deaths, and those of so many more soldiers and civilians in Ukraine, are the tragic outcome of the distortion of history and of truth that dominate political discourse in today’s Russia.

Sarah Taylor is Canada’s Ambassador to the Russian Federation.