Trudeau’s Cri de Guerre for the Middle Class

The conventional wisdom that resides at the confluence of politics and economics has, for the decade since the financial cataclysm, maintained that economic growth and political success hinge on the middle class — at least for progressive governments. Justin Trudeau staked his electoral fate on this bet in 2015 and has rewarded the middle class in four budgets. John Delacourt looks at whether that bargain will hold in the upcoming campaign.

John Delacourt

With the tabling of 2019’s federal budget, the Trudeau government has presented its final policy statement on the achievements it can claim for “the middle class and those hoping to join it.” The last three and a half years of the Liberal government’s mandate have been marked by bold new initiatives to bolster the claim that they have defined their spending priorities by this lodestar. These have included the “middle class tax cut,” the changes to the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS) and, most significantly, the new Canada Child Benefit (CCB). The latter’s social impact is particularly significant; 278,000 Canadian children have been lifted out of poverty since 2015. The Liberals have introduced an Infrastructure Bank and a national housing strategy because spending on “social infrastructure,” a term first heard during the 2015 campaign, can encourage diversity, spur economic growth and increase the real gross domestic product (GDP). All of these initiatives have resonance especially in the larger communities where the aspirational middle class gather to create start-ups and work in the sectors that generate job growth.

Yet the Trudeau government has never really defined the middle class in terms of real income, despite its marked focus on tax policy for this demographic. The closest it has come was in September, 2017. Transport Minister Marc Garneau gave his response to a written question submitted by Conservative MP Kelly Block. The minister provided no income number:

“The government of Canada defines the middle class using a broad set of characteristics that includes values, lifestyle, and income. Middle-class values are values that are common to most Canadians from all backgrounds, who believe in working hard to get ahead and hope for a better future for their children. Middle-class families also aspire to a lifestyle that typically includes adequate housing and health care, educational opportunities for their children, a secure retirement, job security, and adequate income for modest spending on leisure pursuits, among other characteristics.”

One look at the graphics (see Kevin Page’s piece in this issue) on income disparity — and whose slice of the economic pie has grown over the last four decades — suggests this government has targeted an important phenomenon. It is one that French economist Thomas Piketty articulated most effectively in his landmark book Capital in the 21st Century, back in 2013. The rise of the 1 Percent’s income (in Canada, those making over approximately $380, 000) has been dramatic and with it, a polarization effect has emerged in democracies around the world. All the more reason to be precise about the metrics for public policy, especially when you’re basing your budgets on such figures as, say, a debt-to-GDP ratio.

Does this kind of precision matter, given that budgets live and die as political documents? It could be argued that what Garneau articulated was a value statement, marked by phrases that appeal to a general understanding of who deserves a sense of long-term income security and prosperity: those “who believe in working hard,” whose hope for the basics are “adequate,” and who hope to earn enough disposable income for “modest spending” on leisure pursuits. The middle class could ultimately be defined by whom they are not; those who felt the impact when a new income tax rate of 33 per cent was introduced for individuals who earn more than $200,000 a year in taxable income. Yet it’s entirely plausible that there are many households with either single-income earnings or combined earnings not markedly above or below that number who feel they are struggling — and even “house poor” — living in Toronto or Vancouver.

Despite the generally strong performance of the economy over the last four years, especially with job growth, this government is suffering from, for want of a better term, a “deliverology challenge.” The Bloomberg Nanos Canadian Consumer Confidence Index has been trending downward since early 2017, around the time of Garneau’s brief speech in the House. That was before the blunder of Morneau’s proposed tax measures on small business, before the India trip, before the unfolding, puzzling drama of the SNC-Lavalin affair, related to deliberations around a possible remediation agreement for the company. This last turn in Liberal fortunes has led to the loss of confidence in Trudeau’s cabinet by two former high-profile stars within that very chamber. What the mantra of “working hard for the middle class” is addressing, more than it is any metric of prosperity, is the validity of a hope narrative through a period of increasing global uncertainty — when the new NAFTA, Brexit, and the Huawei controversy underscore the circumscribed role the federal government has played with issues of global import over the last four years.

This last budget is a cri de coeur for those voters who are finding it hard to be optimistic, all things considered. This is Morneau tabling the last declaration of intent and promise for the strategically amorphous middle class. There’s a nod to millennials, a key Liberal demographic, with the reintroduction of a First-Time Home Buyer Incentive, a shared equity mortgage program. There’s an enhancement in the Guaranteed Income Supplement earnings exemption for seniors. Seniors’ voter intention numbers are trending towards the Conservatives; the Liberals need to win a significant portion of them back. There’s also a strong signal that a pharmacare plan might just fill in the gaps for those who struggle with limited coverage and expensive needs. Perhaps most important component for an economy evolving at a faster rate than its workforce is the new Canada Training Benefit which will give employees resources to take time off and access skills retraining. All of these measures amount to one clarion call to those who gave Trudeau and his team a majority mandate back in 2015: we’re still there for you, and more than ever, we’re going to deliver on what is going to make a difference for your quality of life — and the quality of life for your kids and your parents. Regardless of how complex the challenges have proven to be over the last four years, this government wants to affirm it hasn’t lost its focus on the Canadians who not only provide its political base but who act as the country’s economic engine.

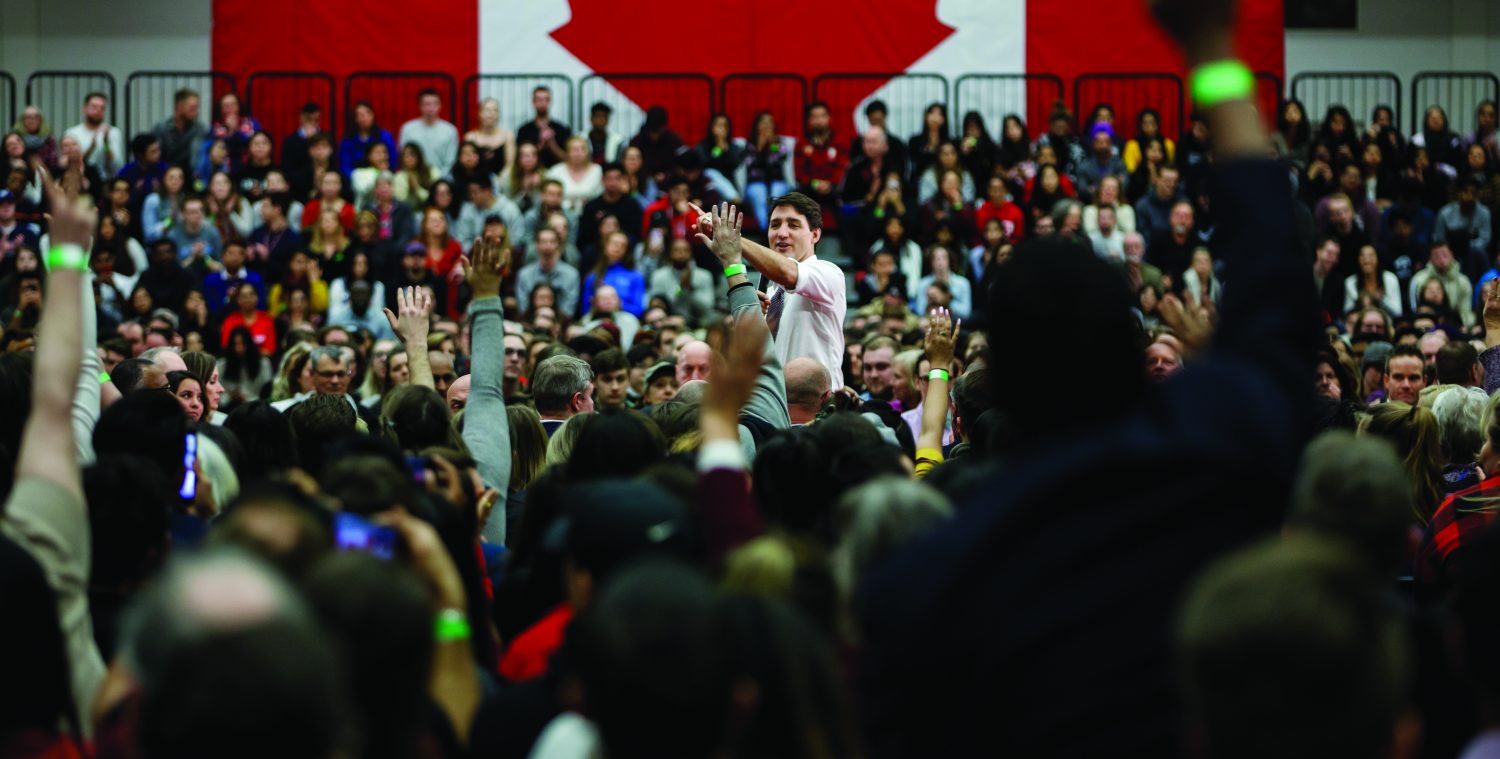

This is meant to translate on election day, of course. Because not only is the budget a cri de coeur, it’s a cri de guerre. Given that approximately sixty percent of all legislation passed by this government has been amended in the Senate, there is every indication the chamber of sober second thought might be less than co-operative rubber stamping every new expenditure. With nine short weeks before the House of Commons rises for the last time before election day, the commitments in this budget could become the basis for the first draft of a campaign platform. There could be worse outcomes, given that Trudeau has proven himself a highly charismatic and effective campaigner. A significant number of worker bees from Kathleen Wynne’s 2014 campaign team are now working for Trudeau. Many of them are proven ground game operatives who pulled off an impressive victory for the premier when her approval numbers also took a huge hit (but they remained in Ottawa, working for Trudeau, during the last provincial campaign). This team might just need to get the Prime Minister in the right rooms — the banquet halls in the outer reaches of the GTA and the 905, the community halls in the lower mainland and in suburban Montreal — to reconnect with that middle class this budget has so urgently attempted to speak to once again. There are no big-ticket items in the Liberals’ last budget, no commitments that have the flash of a change narrative. Yet there might be enough, sprinkled across the demographic spectrum that still hope to believe in Trudeau, to carry the day on the hustings.

John Delacourt, Vice President of Ensight Canada in Ottawa, is a former director of communications for the Liberal Research Bureau and the author of two books, including a mystery novel.