Top O’ the Maelstrom to Ya

Douglas Porter

March 10, 2023

- mael’strom, n. 1) a powerful often violent whirlpool sucking in all objects within a given radius. 2) a great confusion.

Markets are still struggling to find their equilibrium a week after regulators took control of SVB (and then Signature Bank), whose woes have sparked intense liquidity concerns among regional banks. A back-and-forth week saw the focus ping-pong across continents, and a wide variety of both official and private support systems were put in place to calm the waters. The late-week news that banks tapped the Fed discount window for a record $152.9 billion in the week to March 15, and the new Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) for another $11.9 billion, was seen as a sign of high stress, further roiling markets. The large figure also put the $30 billion in fresh deposits from 11 banks for First Republic and the SFr50 billion (US$54 billion) line for Credit Suisse into perspective.

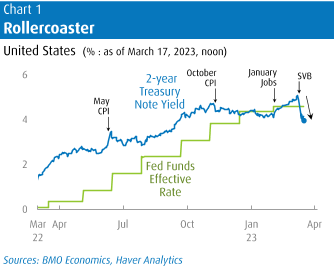

While clearly a fluid situation, the major net market move has been a massive step down in expectations of central bank rates and a secondary hit to oil prices. This combination has sliced bond yields; at one point, U.S. two-year yields were down 130 bps in the space of five trading days, by far the largest such adjustment since October 1987. By Friday morning, they were back below 4%, down 65 bps on the week. Equity markets, while under pressure, have mostly played it cool (aside from bank stocks), with the Nasdaq rising this week and the S&P 500 nudging up on net. The TSX wasn’t as fortunate, as a $10 drop in oil prices (to $66) and a heavy financial services weighting clipped the index to a 2023 low.

Amid the turbulence, the Fed must now balance the financial instability against still-hot inflation. While this week’s key CPI report was mostly as expected, and the PPI was even on the mild side, the reality is that core inflation simply is not budging. Based on almost any metric of core and almost any time period over the past year, the message is the same—underlying inflation is settling into a range just above 5%. We noted that the 0.45% rise in core CPI in February, which is equivalent to a 5.6% annualized pace, was larger than anything seen in the 25 years prior to the pandemic, but was merely in line with the average of the past year. Certainly, there are plenty of grounds for optimism on the outlook for milder inflation—the steep drop in oil, much-improved supply chains, slipping home prices, and business surveys pointing to easing price gains. But the Fed must be unnerved by the stickiness of core prices.

Taking these heavily conflicting factors together, we are holding to our call that the Fed will lift rates 25 bps at next week’s meeting to 4.75%-to-5.00%, assuming no major new news breaks before the meeting. We are also maintaining the view that they will deliver one final hike in May, and then hold at that 5.00%-to-5.25% range through the second half of the year. Even amid the violent swings of the past few weeks, this was our original call—which swiftly went from being far below the market, to well above, to almost right in line, in the space of about 10 days. Of course, the crucial point is that the risks to our call have swung abruptly from the high side to the low side. But the ECB’s icy-veined decision to hike 50 bps this week shows that central banks believe that the inflation fight must proceed, even as they attempt to ringfence the financial risks.

And what about the Bank of Canada? Just one week after stepping to the sidelines—can it only be a week?—market pricing has also adjusted dramatically for the Bank. A pair of strong employment reports to start the year, and a string of other solid indicators for January, had many looking for the Bank to resume rate hikes later this year, at least until last Friday. Now, after the global banking turmoil, markets are priced for at least two rate cuts by the end of 2023. And while the drop in bond yields hasn’t been quite as ferocious as stateside, GoC 2-year yields have plunged 70 bps in barely a week, with the important 5-year falling almost the same to well below 3%.

Despite the aggressive market pricing, the bar for rate cuts is very high. After all, the combination of a deep drop in bond yields, a weak currency, and broadly flat equities means that financial market conditions have loosened. There are even signs that the humbled housing sector is picking itself off the mat. While sales were down 40% y/y in February, and prices off 16% from the record high a year ago, a dearth of new listings has improved the market balance. And, the BoC’s pause, combined with the sharp drop in longer-term yields, will give borrowers some confidence that the worst is over for rates. We don’t look for a quick turn in the sector—not with household debt at 180% of income, butting up against 425 bps of rate hikes in the past year—but it may soon stop dragging heavily on growth.

Canada’s inflation rate is one of the lowest in the industrialized world, but it’s still running more than double the BoC’s target. Tuesday’s CPI report should largely echo the U.S. result, although a small seasonally adjusted rise could clip the headline rate to 5.3% (versus 8.5% in the Euro Area, and 6.0% for the U.S.). Gasoline prices have vanished as an inflation driver, dropping 12% from year-ago levels in recent days, but core has stepped into the void. We look for most core metrics to hold close to 5% in February, not far from U.S. and Euro Area trends.

Besides the ongoing battle with inflation, central banks will also need to determine to what extent the economic outlook has been hit by the financial squall. In a very early sign, the University of Michigan’s survey found consumer sentiment pulled back more than expected in March, but it’s still well above last summer’s lows. The drop in gasoline prices has likely played a big role there, as 1-year inflation expectations of 3.8% are at their lowest since early 2021. Even the five-year inflation outlook has dipped to 2.8%—recall, a jump in this metric above 3% last summer was a key reason the Fed accelerated the pace of rate hikes to 75 bps a clip.

More broadly, the inevitable tightening in credit conditions that will emerge from the turmoil will dampen economic growth. Full disclosure, up until the past week, our call for a shallow recession in North America was looking dubious, especially given the relentless strength in employment and incomes. Unfortunately, the call now looks all too realistic. Pronounced softness in regional manufacturing surveys in March suggests that growth may finally be succumbing to the barrage of rate hikes. And while sub-200k initial jobless claims show the job market hasn’t buckled, the mounting layoff wave (Meta this week) points to a cooling ahead. Even with the surprisingly resilient start to the year, we look for GDP growth to average just 0.7% in both the U.S. and Canada for 2023—only four of the past 40 years have been slower.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.