Time to Revitalize Canada’s Foreign Service

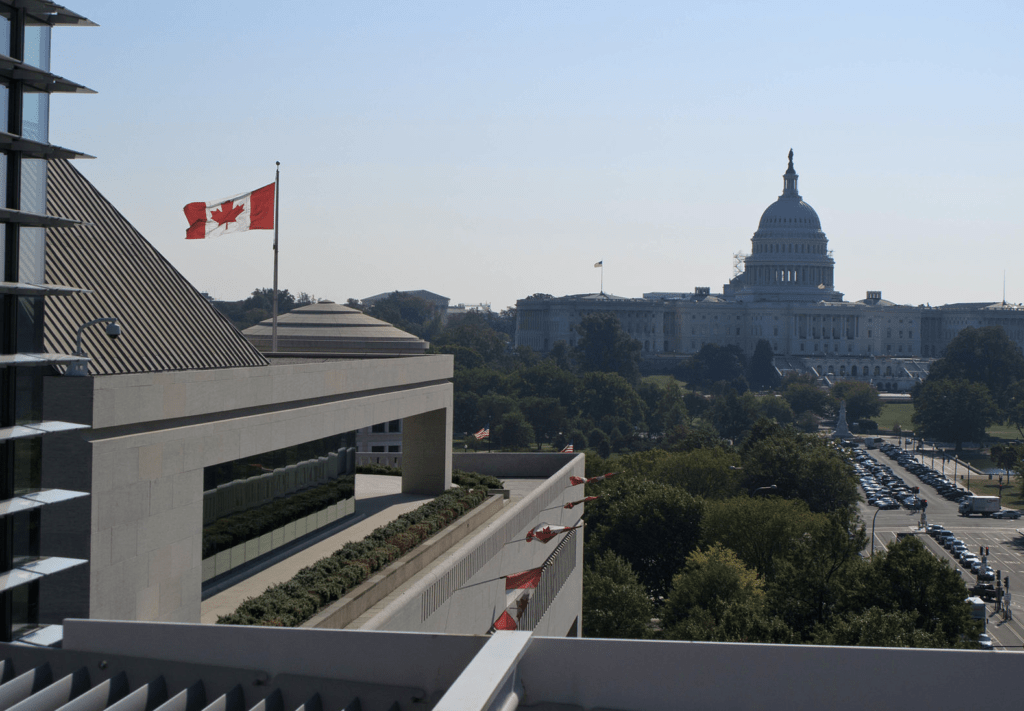

Canada’s embassy to the United States, Washington, DC/Wikimedia Commons

Canada’s embassy to the United States, Washington, DC/Wikimedia Commons

Colin Robertson

May 8, 2022

In a world that is increasingly confrontational, diplomacy matters more than ever. So, it is timely that the Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade is examining the “Canadian foreign service and elements of the foreign policy machinery within Global Affairs Canada.”

If their work prods the government into investing more in our diplomatic service, it will be resources well spent. As Canada’s eyes, ears and voice, reflecting our values and protecting our interests beyond our borders, these times require a strong Canadian foreign service.

The last serious study of the foreign service, the McDougall Report, was commissioned by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau in 1980 and completed 13 months later. A new review is overdue and expected to be completed in an equally timely fashion.

The Senate study is the initiative of its chair, Peter Boehm, and vice chair, Peter Harder, two former foreign service officers with distinguished careers at home and abroad. It will build on and likely complement an earlier Senate study, Cultural Diplomacy at the Front Stage of Canada’s Foreign Policy, the initiative of Senator Pat Bovey, whose professional career included directing the Victoria and Winnipeg art galleries.

As a middle power contiguous to a superpower, more than most nations our sense of identity is realized by how we act and are seen to act abroad. More than most nations, our prosperity depends on our ability to trade and invest abroad. As does our ability to recruit immigrants and refugees. To successfully achieve these objectives, we rely on our foreign service.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Canada’s foreign service was instrumental in helping to build the rules-based order that, for much of the last 77 years, reinforced global peace and security, permitting unprecedented global growth.

Half of our heads of mission are women and women make up 53 percent of our foreign service, up from less than 25 percent in 1981. Visible minorities and members of the LGBTQ+ community represent 8 and 10 percent of the foreign service respectively.

If American diplomats were the architects, Canadian diplomats were the engineers of post-war multilateral institution-building. Lester Pearson, Hume Wrong, Norman Robertson and Escott Reid introduced the principle of “functionalism”; if you have interests, competence and capability, then you earn a place at the top table, regardless of size. It has become the guiding light of Canadian foreign policy, leading to achievements such as the creation of peacekeeping, the end of apartheid in South Africa, the Ottawa Treaty on landmines and the International Criminal Court.

Canada is not a great world power, but in certain sectors — food and energy, for instance — we have vital interests and capacity. Coupled with the leadership and personal support of prime ministers such as Louis St-Laurent, Lester Pearson, Pierre Trudeau, Brian Mulroney and Jean Chrétien, we gained a place at the table. What smoothed our way was the effective diplomacy of our foreign service.

Internationalists by conviction, our post-war diplomats were realists by experience, an attitude that continues to characterize Canadian diplomacy. They also personified the qualities we still seek in our foreign service:

- Adaptability: Dispatched among datelines around the globe and back to headquarters like homing pigeons, officers must adapt fluidly to new cultures and pick up new skills.

- Engagement and Communications: In a networked world, officers must possess the vital ability to personally engage in the single-minded pursuit of the national interest and then communicate analysis and recommendations to our foreign and domestic interlocutors.

- Empathy: Officers must possess the curiosity and interest to master the elements, values and languages of other peoples. Cultivating relationships is a lot easier when we respect people enough to know them. Understanding where our adversaries are coming from helps prevent them from becoming enemies. In the contest between open and closed systems that is likely to dominate this century, empathy reflecting our values is a powerful asset.

While the qualities remain the same, the current foreign service looks much different from the mostly male, mostly anglophone generation of Lester Pearson. Half of our heads of mission are women and women make up 53 percent of our foreign service, up from less than 25 percent in 1981. Visible minorities and members of the LGBTQ+ community represent 8 and 10 percent of the foreign service respectively.

As our world transforms so must our foreign service. Here are 10 recommendations that I believe will help in its transformation to meet the challenges of the 21st century:

1. More foreign service staff, sufficient that we have surge capacity for calamities and to allow for training, secondments, exchanges, and personal leave. In a Global Affairs department of nearly 13,000 that is part of the 320,000-member public service, the foreign service numbers just over 2,400, or less than a percentage of the total public service.

Our international presence has grown to 175 foreign missions. While our foreign ministry has expanded fourfold since Pierre Trudeau was prime minister, the foreign service has only increased a little less than 25 percent. We need more officers. Our pluralism means that we are one of the few countries in the world that can build a foreign service that looks like the entire world. This is an image few others can present and we need to capitalize on it.

Since Pierre Trudeau was prime minister, the global population has nearly doubled from 4.4 to 7.8 billion while Canada’s population has grown from 25 million to its current 38 million. One in five Canadians is born abroad. In Toronto, our biggest city, half the population was born abroad. Canadian trade, as a percentage of GDP, has expanded from 46 percent to 65 percent.

Both our trade and immigration are enabled by the foreign service. When we strove to meet Pearson’s target of 0.7 percent of GDP to development assistance, led by the Canadian International Development Agency, our diplomats helped to bridge the north-south divide, often utilizing Canadian business prowess, especially in engineering.

The personal interests of Canadians, who before the pandemic were traveling more than ever before, is also the responsibility of our diplomats. Inevitably, Canadians encounter mishaps – injuries, robberies, arrests – that require our consular services to step in and help. In the case of calamities such as the COVID pandemic, strife in Lebanon, or a tsunami in the Indo-Pacific, it is on-the-ground consular officers who bring those Canadians home. While 1-800 lines are useful, nothing beats having diplomats on the ground to help those in need.

We also, quite literally, need more foreign service: Increasingly, we are home-bound rather than foreign-based. When I joined the foreign service, half of us were abroad and half at home. Today, only about 18 percent are posted abroad. It’s not possible to give and get a Canadian perspective when our foreign service is home-bound. It costs more to post them abroad but our interests require a strong presence overseas.

2. More geographic and functional specialists. In recent years we have embraced the “cult of the manager” at the expense of specialized expertise.

I will never forget a briefing during Pierre Trudeau’s East-West peace initiative that involved a newly arrived deputy minister who had not served in the foreign service. Allan MacEachen was foreign minister for a second time, in addition to his role as deputy prime minister. He quizzed the deputy on some facts. The deputy paused and then said he’d have to ask others, saying that his job was to “manage” the department. MacEachen nodded but never invited him back. He told us that he expected his diplomats to “know their stuff”. So did Pierre Trudeau. While he had once dismissed the foreign service, saying he learned more from reading the newspaper, he — like most of his successors as prime minister — came to appreciate and rely on the versatility and expertise of Canada’s foreign service.

The reputation of the foreign service depends on its expertise and experience. We can contract bean-counters but developing foreign service expertise is a life-long vocation of learning languages and understanding foreign cultures through repeated postings as well as reinforcing that knowledge and constantly expanding our networks of contacts.

3. “Duty of Care”, a recently introduced (2017) concept of ‘risk management’ that handicaps Canadian diplomats from working in difficult circumstances, needs review and clarification. Foreign service officers expect to serve in difficult circumstances. Like our military, we are – and should be – compensated accordingly. If we want to bring a Canadian perspective to the top table, we need to be in places like Kyiv, Tehran, and Pyongyang. With protection, we also need to accept difficult circumstances as part of the job.

4. Recognition, including a career track, for locally engaged staff (LES). Whether foreign nationals or expatriate Canadians, they keep our offices abroad running efficiently, providing residual memory and continuity and, in my experience, they have the best networks of the people we need to engage. They are an under-appreciated asset and they need champions.

5. Better utilization of honorary consuls, especially in the United States, where we should have representation in every state. With three-quarters of our exports destined to the US, and with US sources accounting for over two-thirds of our foreign investment, we need representation in every state to both advance our interests and head off the perpetual challenge posed by American protectionism. Honorary consuls, who can offer the value-added of longevity in post, can make a difference.

6. More emphasis on partnerships with provincial representatives, who complement our work abroad, especially when it comes to trade and investment. With 33 offices abroad, eleven of them in the US, Quebec has the most sophisticated provincial foreign service and it is a model for other provinces as they expand their networks abroad.

7. Political appointments, yes, but sparingly. Those with political backgrounds have proven especially effective in heading our US missions where all interests are political. But diplomacy is a vocation that requires experience and expertise. There is always the temptation to use foreign postings as a reward. Many rise to the role, but we should not use ambassadorial appointments as a sinecure.

8. More use of data and technology. Algorithmic protocols are now more important to diplomats than the protocol of table placement. Measurement also matters and through investments in technology, knowledge management and diagnostics, the foreign service can leverage data to our advantage.

9. More public diplomacy. Outreach, applying social media, needs to go beyond the conventional circuit of business, bureaucrats and fellow diplomats to include innovators, thought leaders, mayors, civil society and those who share our values. The government also needs to fully implement the recommendations of the Senate report Cultural Diplomacy at the Front Stage of Canada’s Foreign Policy, especially those relating to the revival of a Canadian studies program and the creation of a comprehensive cultural diplomacy strategy, resourced and then measured.

For an insight into the effectiveness of public diplomacy in advancing Canadian interests, read Gary Smith’s recent memoir Ice War Diplomat in which he describes the tremendous diplomatic value achieved through the 1972 Canada-Russia hockey series. We may soon need to resurrect that playbook.

10. As to foreign ministry machinery, form follows function. That form must be sufficiently adaptable to reflect the priorities of the government while avoiding reorganizations that create chaos and deadlock. Middle powers such as Canada must mostly react to events but an annual government priorities statement would provide focus for our limited resources.

Canada’s global interests are best served with a professional and muscular foreign service. For most of the past decade, successive governments, Conservative and Liberal, have starved what was once the world’s premier diplomatic service. If the Conservatives distrusted their diplomats and treated them with contempt, the Liberals took them for granted. Recruitment was halted, budgets were sliced and our residences abroad were sold off, ignoring the fact that. in the host country, lunch or dinner at the Canadian Residence was considered a prized invitation. These political leaders forgot Jean Chrétien’s canny observation that “you don’t do diplomacy out of the basement.” It’s time for redress.

Justin Trudeau is now the senior member of the G7 and, if he is like most prime ministers who have formed a government more than once, he will be looking to leave an international legacy. The current global distemper certainly provides much opportunity for Canadian bridge-building. Foreign Affairs Minister Mélanie Joly is astute and engaged. Crises, especially the Russian invasion of Ukraine, have necessitated that Joly quickly establish a network of her own that includes US Secretary of State Antony Blinken. Canadians will embrace a revival of the job we have always best served in international affairs, that of helpful fixer. But it will require the proper resourcing and revitalization of our foreign service so that it can do its job.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, Senior Fellow of the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa, is a former career foreign service officer who served as consul general to Los Angeles and head of advocacy at the Canadian Embassy in Washington.