Through the Lens of Language

Between the experience of his career covering Quebec politics during the most crucial chapter of the province’s—and the country’s—history and his role as commissioner of official languages, Graham Fraser possesses a unique perspective on Canada’s defining national issue: language. He also inherited his father’s sense of the Canadian idea.

Graham Fraser

When I was in my last year of high school, 55 years ago, my father, Blair Fraser, spoke at the graduation ceremony, and used the occasion to talk about his idea of the country. It was an idea that he later used in A Centennial Sermon in 1967, and in the conclusion of his only book, published later that year, The Search for Identity.

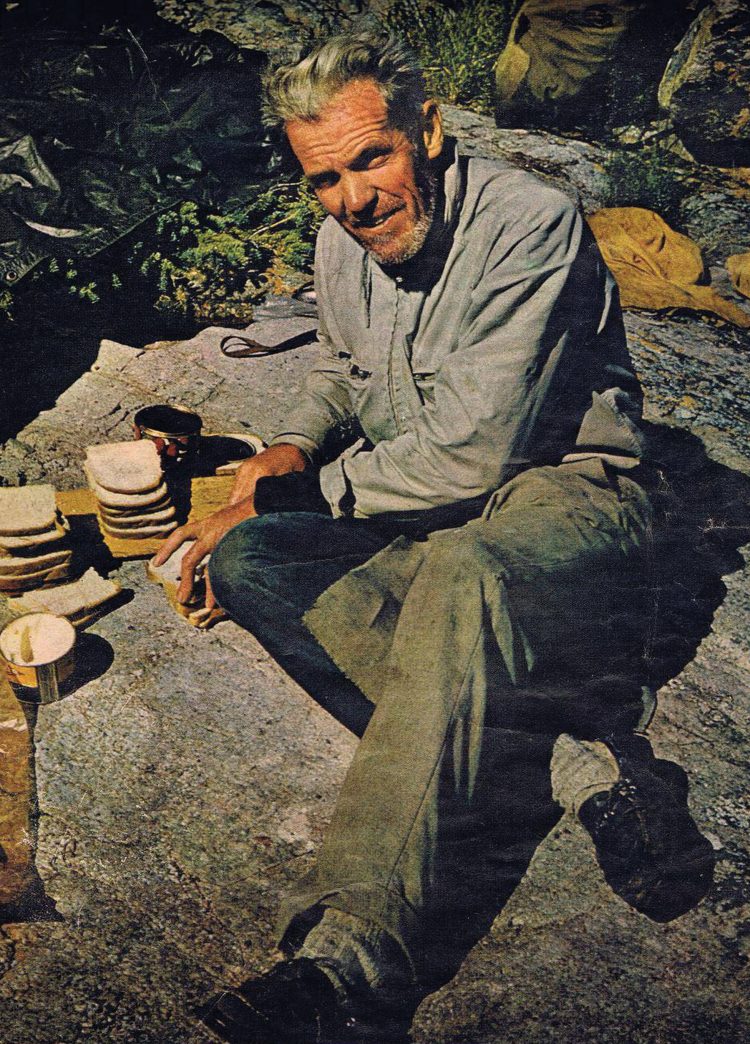

His idea was that what defined the country was its nearness to the wilderness, to what he called “the cleansing experience of solitude.” He posited that mutual affection is not a national characteristic. “Never in their history have Canadians demonstrated any warm affection for each other,” he wrote. “Loyalties have always been parochial, mutual hostilities chronic.” Born, raised and educated in the Maritimes, he moved to Montreal, worked as a reporter and editor, married, and learned French before moving to Ottawa from where he travelled the country and the world for Maclean’s, and retraced most of the routes of the voyageurs in a canoe. The Canadian shield, its lakes and rivers, inspired him more than did politicians or clergymen.

He had intended to write a book on the Quebec independence movement, having written about Quebec nationalism since the 1940s; his last published article before he died in a canoeing accident in 1968 was a profile of René Lévesque.

Indeed, his view that the strains of biculturalism were “easing off, as English Canadians rush to learn French and English-speaking provinces move, still grudgingly but definitively, toward the establishment of schools in which French is the language of instruction” proved to be more optimistic than prescient. Language continued to be a dividing line and a source of tension for much of the half-century that followed. It remains a challenge.

My father ended his comments to my graduation class in 1964 with the advice—at a time when the Brain Drain was a Canadian worry—that they should not feel guilty if they decided to move to the United States.

“But if you love it, stay, and it will make you very happy.”

Good advice, and a modest Canadian idea. It moved me then, and it moves me now.

I followed my father into journalism—he died after my first week at the Toronto Star—and as things turned out, less than a year after his death I spent a week travelling with René Lévesque, and I would go on to spend the critical years of my career in journalism following him and his government. The story of Canada that I tried to tell was that of a country wrestling with language and constitutional tensions.

I grew up with my father’s idea of Canada—the story of a country of networks through the wilderness created from the canoe routes paddled by French-Canadian voyageurs—and saw how it provided the underpinning for other stories: Harold Innis’ story of the fur trade; Pierre Berton’s story of the railway; Glenn Gould’s idea of Canada’s north; Marshall McLuhan’s theories of communication ; F. R. Scott’s idea of justice; Jane Jacobs’ views of urbanism; Thomson Highway’s indigenous mysticism; and Charles Taylor’s and Will Kymlicka’s ideas about community, language and diversity.

At the same time, Quebec was telling its own stories about the country—through debates between Wilfrid Laurier and Henri Bourassa and between Pierre Trudeau and René Lévesque and by voices as diverse as those of Gilles Vigneault, André Laurendeau, Michel Tremblay, Dany Laferrière, Robert Lepage, Kim Thuy, Gérard Bouchard and Boucar Diouf. Each of these in some way, whether intending to or not, articulated a Canadian idea. But the Canadian idea with the longest history and the deepest fault line has been that of language. Language has been for Canada what race has been for the United States and class has been for Great Britain: a defining tension, and a continuing challenge.

There are ways in which our struggles over the last half-century have been successful. The income disparity between English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians identified by the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism 50 years ago has been eliminated. (This is a success that contrasts with the continuing racial and class income disparities in the U.S. and Britain.) Bilingualism has become a critical qualification for political leadership—as he had hoped he would be, Lester Pearson is our last unilingual prime minister. But bilingualism is still very much a minority characteristic among English-speaking Canadians outside Quebec, with fewer than 10 per cent able to carry on a conversation in French. (Just over 40 per cent of French-speaking Quebecers can carry on a conversation in English—still a minority.)

Anniversaries are useful moments for reflection, and if Canada 150 was a lost opportunity, 2020 offers a more sobering moment for consideration of what the country has achieved or failed to accomplish. For that will be the 25th anniversary of the 1995 Quebec referendum, when Canada came within 55,000 votes of the kind of existential crisis that Britain is now living through following the Brexit referendum. What’s changed? There was the transfer of certain responsibilities to Québec, a greater visibility of Canadian symbols (the unfortunate sponsorship program, riddled with corruption and kickbacks), and the Supreme Court reference on Quebec secession.

What was not done? There has been no effort made to increase the contact between the rest of Canada and Québec; there were no Québec studies programs established in English-Canadian universities outside Québec; there was no Canadian equivalent to the European Erasmus program established to encourage students in French-speaking and English-speaking universities to spend a year in an institution of the other language. In fact, the one such institutional program that existed, Collège Militaire Royal, which received students from Kingston’s Royal Military College, was shut down and is only now close to resuming its previous status. There was no systematic attempt to make unilingual Quebecers aware that they could be served in French in national parks across Canada—and no renewed effort to ensure that this was, in fact, the case. Exchanges did exist, as they still do, but they still constitute a drop in the bucket.

In 2005, the Official Languages Act was amended to give federal institutions the obligation to take positive measures for the growth and development of minority language communities. However, in 2018, Judge Gascon of the Federal Court issued a decision in which he gave a meticulous, word by word analysis to demonstrate that the language of the amended clause was not as binding as that in the other parts of the Act.

What are the other changes that have occurred over the last 25 years? We have seen a number of post-secondary institutions continue to take small steps to ensure that university graduates are fully bilingual: the immersion program at the University of Ottawa, the success of the Bureau des affaires francophones et francophiles (BAFF) at Simon Fraser, the transformation of Collège St. Boniface into a university and the continuing work being done by York University’s Glendon College and Université Ste-Anne. However, these remain boutique programs. There is no equivalent to the European Erasmus program, which finances thousands of students to study in other European countries, to partake in the idea of Europe.

On the other hand, the government of Ontario has abolished the independent position of Commissioner of French-language Services and shelved the plans for a French-language university. We have seen a slight decline in bilingualism among Anglophones.

A columnist in The Economist wrote recently that “Canadian politicians are usually bilingual as a matter of course.” If only that were true. It is true that bilingualism is a defining qualification for political party leadership, but many Canadian politicians do not meet that requirement.

We have seen a continuing series of Action Plans for Official Languages—which were renamed Roadmaps by the Conservatives. These have involved millions of dollars being directed towards minority language communities, and French Second Language learning. It is a proof of their success that they have survived two changes of government.

However, over the last two decades, under Liberal, Conservative and Liberal governments, these initiatives have had one thing in common: while they have been critically important for the vitality of Canada’s linguistic minority communities, they have been virtually invisible to Canada’ linguistic majorities. The Official Languages Act, understandably, is focussed on the linguistic minorities: their rights, their access to services, to education, to justice. So is the Charter, and the jurisprudence that has flowed from it.

But what has been missing from the discussion is a larger question of Canadian identity. If Canada’s two official languages are seen and understood as key components of national identity, and the health and vitality of the two languages and the cultures expressed in them as critical elements in the definition of the country, then the policy is no longer simply about minority rights.

Canada’s official languages, and the policies that support them, need to be understood and promoted for their importance to the linguistic majorities. Canadians need to feel that our two official languages belong to all of us—whether or not we speak them.

This insight occurred to me when I heard Professor Jennifer Rattray of the University of Winnipeg say, in a discussion of indigenous languages, “I do not speak my language.” That is the feeling that all Canadians should have about English and French: that they are our languages, even if we do not speak them.

We have two national linguistic communities in this country that enjoy national television and radio networks, that generate books, newspapers, movies, songs—not to mention jurisprudence. In some ways, the Francophone majority in Quebec suffers from insecurity, the Anglophone minorities from being misunderstood, that Francophone minorities are invisible and the Anglophone majority is insensitive. This latter phenomenon is not unusual: all majorities tend to be insensitive to the needs of minorities.

Legislation can go part of the way to address these challenges. But it cannot go all the way. When all you’ve got is a hammer everything looks like a nail, and at times, all that minority communities have had has been the hammer of legislation and the anvil of the courts.

But governments at all levels need to lift their eyes and raise their game so that they can convey to all Canadians the essential role that our two languages play in our identity, in the Canadian idea: that is to say, in our history, in our literature, in our films, in our music, in our television, in our welcoming of newcomers, in our presentation of ourselves to the world, and in our creation of a unique North American society, today and in the future.

Graham Fraser is the former Commissioner of Official Languages, serving from 2006-16. A former Ottawa bureau chief of The Globe and Mail, he was also a correspondent of Maclean’s, the Toronto Star and the Montreal Gazette. He is the author of several national bestsellers, including PQ: René Lévesque and the Parti Québécois in Power, and Sorry, I Don’t Speak French: Confronting the Canadian Crisis that Won’t Go Away.