The Wrenching Question in Hong Kong: Should I Stay or Should I Go?

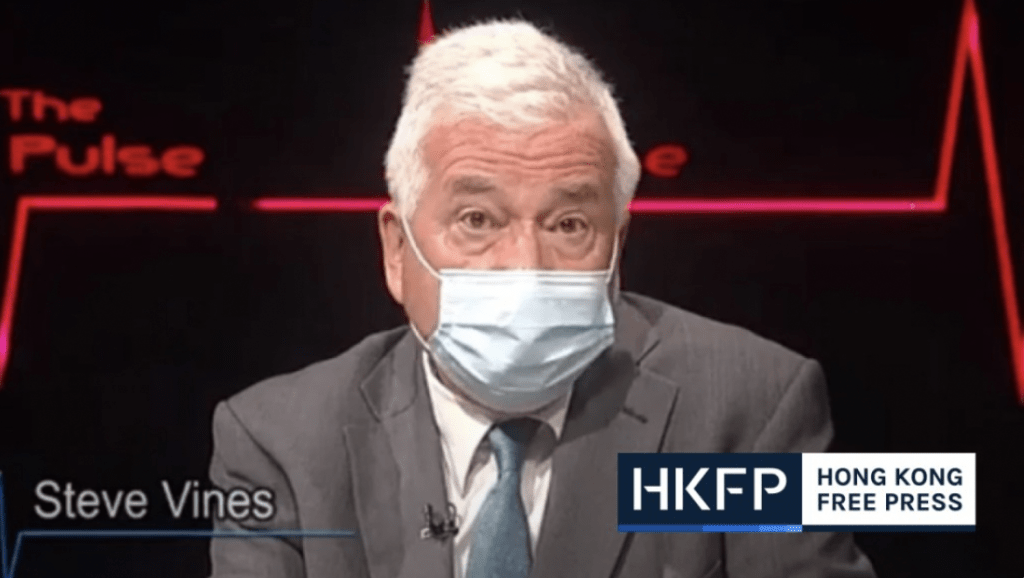

Journalist Steve Vines, who has fled Hong Kong following threats against his safety

As Beijing’s targeting of the free press worsens, many fear that Hong Kong’s long-independent judiciary will be next. Policy contributing writer and former Hong Kong resident Robin Sears looks at the choices made by a journalist friend who has fled, and a high-profile Canadian judge who has chosen to work within the besieged system.

Robin V. Sears

August 6, 2021

As in Berlin in 1936, Shanghai in 1949 and other datelines suddenly facing subjugation by brutal regimes, the existential question for the politically vulnerable in today’s transformed Hong Kong is: “Should I stay or should I go?” A related question for those who hold positions of influence in Asia’s most cosmopolitan city is: “Should I quit or should I raise my voice?”

To outsiders never facing these achingly hard choices, the temptation is to be self-righteously blunt: “Protest! Quit! Leave today!” For those wrestling with these choices, life is a great deal more complicated. Your choice will have an impact on family and friends no matter what it is. Your choice — especially if you are a public figure — will send an important signal to those who follow and respect you.

China has shown little compunction in threatening the families and associates of those who have run afoul of its edicts, whether they live in Hong Kong or Toronto. The former employees of the assailed pro-democracy newspaper Apple Daily — those who are not already facing criminal charges under the totalitarian National Security Law Beijing imposed in 2020 — will have a hard time finding employment, not just because of their former employer’s concocted misdeeds but because of surveillance-state tactics that have industrialized covert harassment in Hong Kong and elsewhere.

This week, one of Hong Kong’s most prominent and influential international journalists, having been threatened that he was next, decided he had no choice but to flee. For Steve Vines — a veteran broadcaster for RTHK, writer for many American, European and local media organizations, including The Guardian, the BBC and The Independent — leaving behind more than three decades of his life and career was a wrenching choice. Like many long-term Hong Kong residents, Vines loved the city, the culture, and its people. (I reviewed Vines’ latest book on Hong Kong, Defying the Dragon: Hong Kong, China and the Future of Freedom, for Policy magazine in April).

In a message to friends about his decision to leave, Vines noted the irony that those now in control hate much of what makes Hong Kong unique: its cosmopolitan culture, its vibrant, often messy zest and even its language, Cantonese. Beijing, whose broader anti-democracy activities have been characterized by a zero-tolerance for resistance to its dictates, also sees Hong Kong’s independent spirit as a threat to the power of the state, just as it was to five centuries of earlier emperors.

Vines’ departure is yet another blow to independent journalism in Hong Kong, once the centre of the free press for much of Asia. Its previously vibrant local media, and its status as a regional headquarters for hundreds of foreign correspondents, made it an icon of free speech in Asia. After killing Apple Daily, which was the most popular tabloid, seizing all its assets and laying serious felony charges against many of its executives, Beijing has now begun to squeeze Hong Kong’s public broadcaster, RTHK, into just another state propaganda organ.

Beyond the guarantee of a free press that was one bulwark of the Hong Kong Beijing pledged to respect under the One Country, Two Systems provisions of the UK-China Joint Declaration treaty governing the 1997 handover of the former British colony, the second pillar of democracy under threat is the judiciary. Now, even a cynical businessman who believes that capitalism has always been the sole driver, and who mutters “Who needs cheeky reporters anyway?” will blanch at a corrupted court system. For it is the guarantee of a longstanding right to the protections of English Common Law that planted the seed for and protected Hong Kong’s explosive growth. It gave birth to the entrepôt where local and foreign investors could trade safely and make Chinese investments with the assurance that contract law would protect them.

McLachlin considered her choice carefully, and consulted widely for months in advance of making it. In the end, she appears to have accepted the appeals of Hong Kong lawyers and judges that she stay.

Pressure from Beijing on the Hong Kong courts has been feared for many years. Now, the use of the National Security Law to override statute and precedent has raised anxieties about the safety of placing your intellectual property, your assets, even your employees, in Hong Kong. One guarantor of the city’s judicial independence was the addition to its Court of Final Appeal — the equivalent of Hong Kong’s supreme court — of esteemed jurists from the UK and Commonwealth countries to three-year terms under the Basic Law that governed post-handover Hong Kong until Beijing began arbitrarily overruling it.

One of Canada’s most respected judges, former Supreme Court Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin, is one of the 14 foreign judges currently serving. Her first term was to end later this year and she announced this week her willingness to serve an additional three years. This shocked many Hong Kong Canadians, and some Canadian lawyers, who felt she should have resigned in protest immediately. McLachlin considered her choice carefully, and consulted widely for months in advance of making it. In the end, she appears to have accepted the appeals of Hong Kong lawyers and judges that she stay.

As the head of the Hong Kong Bar Association, Philip Dykes, said in a public appeal, her resignation would signal that something was “seriously amiss” with Hong Kong’s courts. He has a point, for if Justice McLachlin had announced she was quitting it would have been demoralizing to those fighting locally to defend their judicial freedoms. The decisions of both the British judge, Baroness Brenda Hale, and Australian judge James Spigelman, to quit were greeted with shock and dismay by many in the Hong Kong legal community, though public criticism was muted.

McLachlin’s choice is surely the more courageous. If a case is referred to her and her colleagues that clearly has the thumbprint of political interference, she and they will resign — loudly, one expects. She will then come under withering attack by Beijing. The Chinese Communist Party and its local quislings will, however, need to think carefully about what that debacle might do to investor and business confidence in Hong Kong.

The hardliners in Beijing have a yin/yang balance to strike. Their SOEs and private sector companies make up more than three out of four listings on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, now the world’s third largest. They use the city’s global finance networks to raise billions of dollars in investment, and billions more pass through its international banks to the world. Hong Kong today is the financial centre through which twice as much cash sloshes as did at the time of the handover in 1997.

Now that China’s efforts to make Shanghai a truly international finance centre have failed due to ongoing state manipulation, Hong Kong’s importance to Beijing as a capital market has never been greater.

As London and Washington tighten the screws on Chinese listed companies for their opaque shareholding structures and serious gaps in corporate governance and financial disclosure, Hong Kong increasingly becomes the only global financial capital to which they can be sure of unfettered access. The deep irony is that as Beijing threatens to squeeze the city’s legal independence, it risks nudging American and European bankers to pack their bags for Taipei or Singapore, and it risks undermining the one guaranteed point of access to international capital on which their own growth depends.

Now that China’s efforts to make Shanghai a truly international finance centre have failed due to ongoing state manipulation, Hong Kong’s importance to Beijing as a capital market has never been greater. China’s recent crackdown on its own tech giants has wiped out nearly a third of their market cap, shocked international investors and sent them scrambling out of China-only listed stocks.

Beijing regulators convened a confidential meeting with international bankers last week to try to calm the markets. They understand how fragile is their capital market’s reputation, given threats to prevent foreign investors from repatriating earnings, and the recent crackdown.

Shanghai’s scale as a market is also shaky, and increasingly linked to Hong Kong since Beijing allowed Hong Kong-based traders to execute Shanghai and Shenzhen trades from Hong Kong through the Stock Connect scheme launched in 2014. As much as 20 percent of Shanghai trading is forecast to be based in HK by the end of 2022. The only reason Beijing permits this leakage is its awareness that international investors feel safer trading from an independent capital market.

Curiously, though Beijing controls the HKSE and the city’s equivalent of the SEC, it has recently allowed them to toughen and tighten regulation and scrutiny of China’s own HK-listed companies. This is something they have vigorously resisted in Shanghai and Shenzhen, and continue to attack London and New York for insisting on.

Some market watchers believe this is a signal that at least China’s financial bosses understand that weakening HK as a global finance hub weakens China too. It’s not clear that President Xi understands this.

Beijing may succeed in forcing Western journalists out of Hong Kong, and imprisoning those locals who cannot escape, but there are many brave Hong Kong reporters still working to build social media equivalents. They may equally succeed in chilling the independence of Hong Kong’s judiciary, but with it may come the destruction of billions of dollars in Chinese assets, if bankers leave and the market and then property values begin a long slow slide.

Some argue that Beijing will see that as a reasonable price to pay. Perhaps in Xi Jinping’s mind, it is. But in the minds of the millions of Chinese citizens, including all the Party elite who have a significant financial exposure to Hong Kong, perhaps not.

Policy Magazine Contributing Writer Robin V. Sears lived in Tokyo as Ontario’s Agent General for Asia for six years, and later worked in the private sector in Hong Kong for another six years. He is an independent communications consultant based in Ottawa.