The War Supply Shock Awaiting the 2022 Budget

Kevin Page

April 8, 2022

Budget 2022 highlighted the significant uncertainty facing the global economic outlook. The Russian invasion of Ukraine is creating a global supply shock. By disrupting the supply of energy, metals and agricultural commodities, this major geopolitical conflict could have a negative net impact on output and prices for all countries, including Canada.

Budget 2022 chose to adjust its policy framework in the face of these potential dark clouds on the horizon but not its planning framework. Policy spending in Budget 2022 was measured and modest, leaving important fiscal room to address potential future risks.

The planning framework, on the other hand, was based on a (pre-war) February survey of private sector economists. This outlook called for temporary higher price inflation, modest increases in interest rates and relatively strong output growth. It is a great concoction of variables to produce strong projected revenue growth and lower budgetary deficits. The government chose to use the dated baseline. The numbers looked better. There were no contingency reserves to highlight potential downside risks. They addressed a somewhat optimistic planning framework by being cautious with spending.

To the government’s credit, different economic scenarios were added to inform Parliament and Canadians that the government’s fiscal plan can be thrown off track. It is a good planning practice.

To be frank, the geopolitical and economic impact of Russia’s invasion has enormous potential to go from bad to worse. The Russia-Ukraine conflict represents the third major global economic shock over the past 15 years (global financial crisis – 2008; COVID-19 – 2020). The uncertainty facing planners this time is more similar than different.

Why? Russia and Ukraine are major producers of global commodities. Prices for commodities, mainly energy, metals and agriculture are going up. These two countries are critical suppliers to many hundreds of thousands of companies across the globe. Supply chains, famously snarled during the pandemic, are being further disrupted by war and related sanctions. Given the relative importance of exports from these countries, it is proving difficult to find alternative supplies. Higher prices for war-restricted commodities are driving up related commodities (example – higher prices for crude and petroleum derivatives like ethanol and polyester have dragged up prices for other commodities, notably palm oil and cotton).

These two countries are critical suppliers to many hundreds of thousands of companies across the globe. Supply chains, famously snarled during the pandemic, are being further disrupted by war and related sanctions.

Negative supply economic shocks (i.e., like the COVID public health shock and the Russia-Ukraine war) are bad news. They are complicated for policy makers – more complicated than shocks to aggregate demand such as the 2008 global financial crisis.

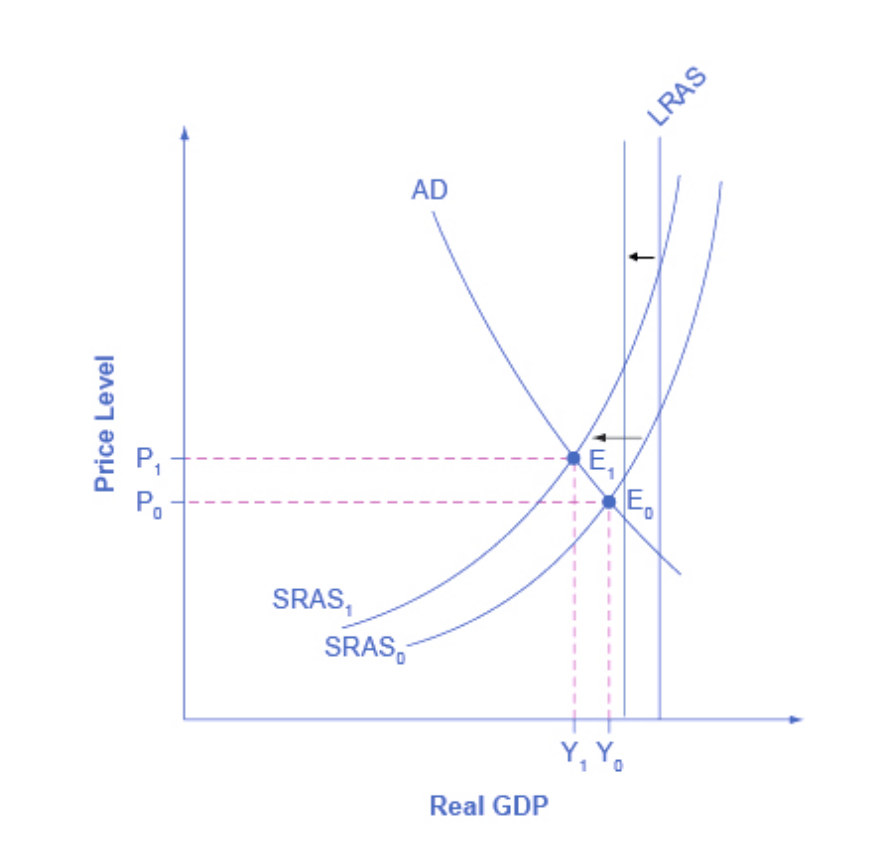

From the graph below, you can see that a leftward shift in the short-run aggregate supply curve (SRAS) – represented by COVID supply bottlenecks and war-related reductions in commodities such as energy, metals and agriculture grain, and so on pushes up prices and reduces output, resulting in higher unemployment.

A misread in the macroeconomic environment could be costly for future potential output, long-run aggregate supply (LRAS) and economic stability.

Monetary and fiscal policy efforts to boost demand in this environment will push prices higher. This would risk locking in higher inflation expectations and a stronger potential future monetary policy response to address inflation. Remember the 1970s and 1980s when expansion policies were used during the OPEC shocks? Inflation rates rose; monetary policies were eventually used to reduce demand (i.e., drive the economy into a recession) and lower inflation.

Policymakers are likely looking at a stagflation environment – weaker-than-anticipated growth; higher-than-anticipated unemployment.

The rules of thumb for economic adjustments are buried in budget documents. A one-year one percent reduction in real GDP bumps up the deficit line by about $5 to $6 billion per year. A sustained one percent (100 basis points) increase in interest rates bumps up the deficit line by $5 to $6 billion per year. By contrast, a one-year one percent increase in inflation rate lowers the deficit by about $2 billion per year. Takeaway – stagflation is not a good economic scenario for public finance.

From a stabilization policy perspective, monetary and fiscal authorities really do not have a lot of wriggle room on the path to policy normalization. Both monetary and fiscal policy are very expansionary. In a higher inflation environment, the Bank of Canada policy rate is sitting at 50 basis points – possibly 1.5 to 2 percent below a longer-term trend policy rate, maybe more. Current forecasts assume the output gap (actual output relative to trend output) will be closed by the end of 2022 or early 2023. This means the projected structural budgetary deficit (the balance that would exist if the economy is operating at trend) is already in the 1 percent of GDP range.

A sustained one percent (100 basis points) increase in interest rates bumps up the deficit line by $5 to $6 billion per year. By contrast, a one-year one percent increase in inflation rate lowers the deficit by about $2 billion per year.

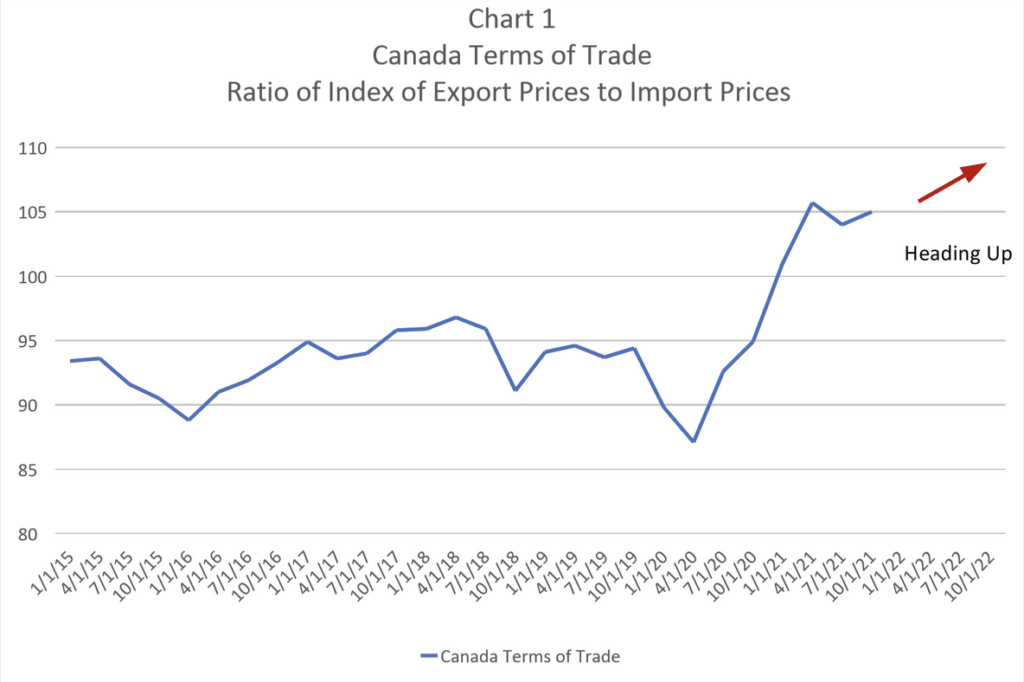

The Budget 2022 planning outlook takes into account the positive first-round impact of the beginning of the Russia-Ukraine war. Because Canada is a major commodity producer we stand to benefit from higher war-related commodity prices. You can see the magnitude of the benefit in the upward movement of Canada’s terms of trade – the ratio of export prices to import prices. This indicator will likely continue to improve as the war and supply shock continues. Higher export prices boost output, jobs and government revenues.

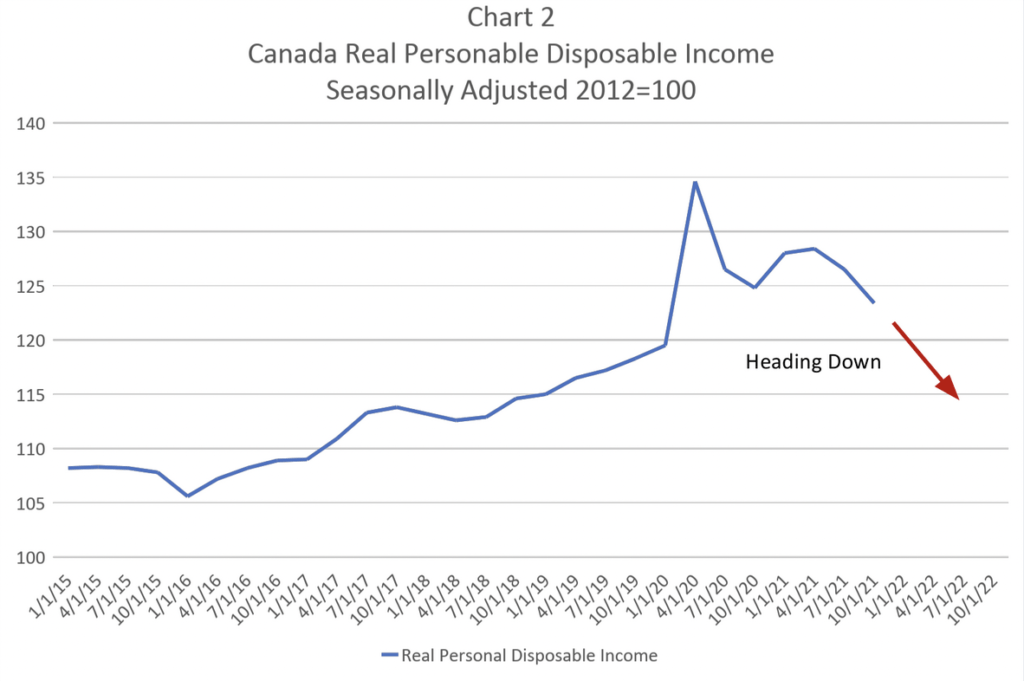

The Budget 2022 planning outlook does not reflect the more negative second round impacts. Canadian households (and businesses) are about to see a significant squeeze in disposable income. Price inflation is currently running more than 5 percent on a year-over-year basis. It is likely that this number will continue to rise in the months ahead. Meanwhile, wages or earnings are running at a much more modest pace – in the 2 to 3 percent range. Real personal disposable incomes are about to get squeezed in a major way. Rising interest rates will compound that squeeze.

It has been said that the future is not uncertain, it is unknowable. Economists are generally not adept at incorporating the potential economic impact of geopolitical conflict in planning outlooks used by policy makers. We need to raise our game. Canada’s political leaders face two challenges. Help Ukrainians in these dire times. Prepare Canada for yet another global supply shock.

Kevin Page is the President of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa, former Parliamentary Budget Officer and a contributing writer for Policy Magazine.