The Three Amigos Takeaway: What Got Done in Mexico City

Colin Robertson

January 12, 2023

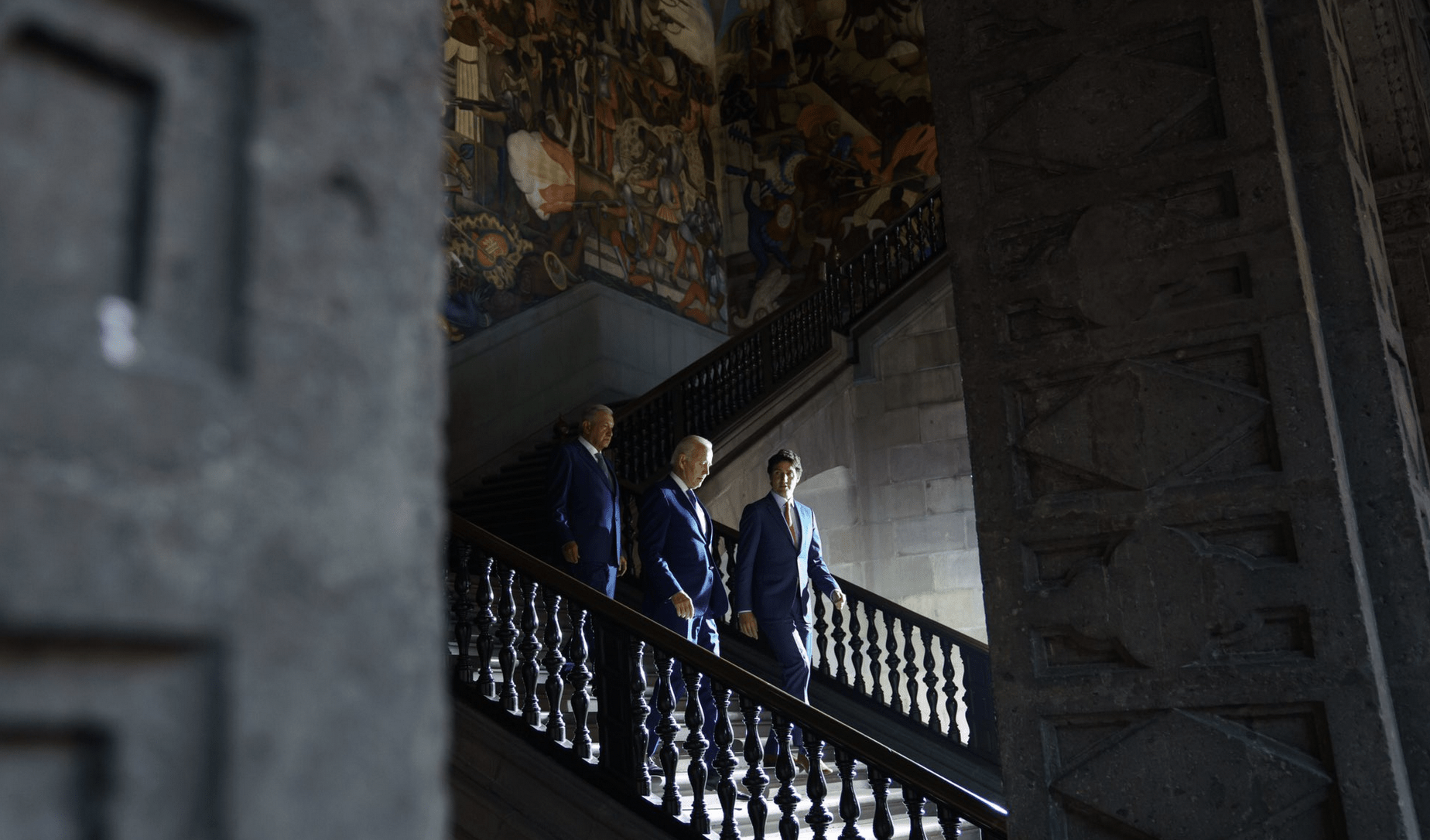

The “North American idea” — closer collaboration for continental common good — got a boost this week when Canada’s Justin Trudeau, Mexico’s Andrés Manuel López Obrador, or AMLO as he is popularly known, and the US’s Joe Biden met for another North American Leaders summit (NALS) in Mexico City. Going forward, the challenge, as with most summits, is translating the intentions laid out in the final communiqué, in this case the Declaration of North America, into results.

It has been over a year since their last get-together, a more perfunctory but useful day in Washington as Biden revived the annual meetings of the “Three Amigos”’ that George W. Bush started with Paul Martin and Vicente Fox at Waco, Texas in 2005. These summits had lapsed during the Trump years.

While the current North American leaders come from the political left, they are not the same. Trudeau is progressive new left. Biden is traditional old left. AMLO is doctrinaire, if not populist, hard left. While Trudeau and Biden are simpatico, it’s not the bromance of Obama and Trudeau. AMLO is known to be difficult, as both Biden and Trudeau have learned on a handful of bilateral files.

As is always the case at NALs, the main focus was on the “dual bilaterals”, the discussion between: AMLO and Biden on guns, migration and drug trafficking that generated most US and Mexican news coverage; Trudeau and Biden on G7 items like Ukraine, Russia and China as well as Haiti, and climate; AMLO and Trudeau on trade, energy and tourism.

The trilateral meeting focused on economic cooperation, climate change and democracy. The final declaration covered six broad areas: diversity, equity and inclusion, with a commitment to fight systemic racism; climate and environment with commitments to lower methane emissions and wastewater; competitiveness with a focus on supply chains, semi-conductors, critical minerals and clean energy; migration and development; health, with a commitment to applying lessons learned from the pandemic; and regional security. The three leaders jointly endorsed the peaceful transfer of power to President Lula da Silva and condemned the January 8th attacks on Brazil’s democracy.

Business in all three countries has consistently been ahead of their national governments in embracing closer economic ties. In an open letter on the eve of the summit, three leading business associations participating in a parallel business trilateral – the Business Council of Canada, US Chamber of Commerce, and Mexico’s Consejo Coordinador Empresarial — pressed leaders to enhance continental economic competitiveness.

They were rewarded with the promise of a cabinet-level summit on semi-conductors, mapping mineral resources across the North American continent and promoting educational investment.

Collectively, the three economies generate about one third of global GDP, and the economic discourse is, increasingly, less about trade than making things together – with 79 percent of Canadian exports incorporated into US manufacturers and 40 percent of the value of Mexican exports to the US composed of components “Made in the USA”.

Given this deep integration, there are always trade disputes and these are a shared, contentious component of these summits. But the renegotiated NAFTA (USMCA/CUSMA/TMEC) includes both stronger enforcement provisions and a rapid response mechanism for labor disputes. For now, it is working.

Yes, there are more disputes – easily tracked on the nifty new Brookings USMCA Tracker – but they are getting action, if not resolution, through dispute settlement. Canada got rapped for dairy protectionism, the US for solar panel protectionism, Mexico for its labour practices and the US for its nationalist interpretation on rules of origin relating to our auto industry.

For Joe Biden, who is now looking to the 2024 presidential election and conscious that his handling of the Mexican border is seen as a liability, the summit netted him a Mexican agreement on a major shift in migration policy that each month will send 30,000 illegal migrants from Cuba, Nicaragua, Haiti and Venezuela back across the border. The quid pro quo is that 30,000 people per month from those countries who get sponsors, background checks and an airline ticket to the US can work legally in the country for two years. That both the left and the right don’t like his new deal on migration means he probably got it right.

Biden also got a boost on the defence front, with the Canadian announcements on the purchase of 88 F-35s worth $19 billion and the gift to Ukraine of a $400 million US-made missile defence system will both bolster collective security and encourage the Germans to send their tanks to Ukraine.

Biden will come to Canada in March, his first visit as president. Those who cluck that waiting two years is too long miss the point. Biden, who visited Ottawa in 2016 as vice president, knows Canada from his years as chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and his relationships with Canadian prime ministers go back to Pierre Trudeau.

All three leaders have secure mandates for at least another couple of years. Let their motto be, per the famous Second World war memo from Bletchley Park to Winston Churchill, ‘Action this Day’.

The upcoming visit does mean that, for the coming weeks, the White House will be looking at Canada and we can be sure our embassies will be pushing our files — especially those in the “Roadmap for a Renewed Canada-US Relationship” — that was launched two years ago next month. While officials say there has been progress, we need a public stocktaking and the visit should ensure that.

Then there is Haiti, a failing state on the cusp of becoming a failed state. It’s been four months since Haitian Prime Minister Ariel Henry appealed for “the immediate deployment of a specialized armed force, in sufficient quantity” to curb the “criminal actions of armed gangs” and two months since UN Deputy Secretary General Amina Mohammed urged every country “with capacity” to heed the Haitian request. Canada’s UN ambassador, Bob Rae, has been handling the file for Ottawa.

President Biden is looking to Canada to “help stabilize” the troubled nation but as Trudeau told reporters, “We’re going to make sure that what we do this time allows for the Haitian people to get the situation under control.”

Trudeau is right to be cautious. If we have learned anything from our experience in Afghanistan and previous experience in Haiti, it is to be very careful about state-building. Haiti would require at least a decade of intense peace-making then peace-keeping to say nothing of the reconstruction of its government, economy, education and health systems. It would need all-party, or at least agreement between the Liberals and Conservatives, to ensure continuity when there is a transition in government.

But mindful of the pitfalls, Haiti needs help and with the Trudeau government committed to doing more to promote democracy and good governance, then why not Haiti? As the late George Shultz once told me, given our relationship with the troubled land – a shared language and our significant Haitian diaspora – if we were to take on Haiti, there would be global appreciation.

The North American idea is not that of the European Union, where sovereignties are shared with the superstructures of a Commission backed by its Brussels-based bureaucracy, a Council of Ministers, and a Parliament that together possess across-the-board legislative and regulatory powers on trade and commerce, foreign policy, migration, climate, energy and environment.

By contrast, the North American idea is based on the three sovereign nations reinforcing their collaboration in the “spirit of community based on interdependence.” The fact-based arguments for integration have not changed since the negotiation of the original NAFTA. There have been successive reports over the years, notably from the Council on Foreign Relations (2014), the Belfer Center (2015), the George W. Bush Institute (2021) and the ongoing work of the Canada and Mexico Institutes at the Wilson Center, including their new book North America 2.0: Forging a Continental Future.

With abundant natural resources, a strong industrial base with pools of self-generated capital, and a market of half a million people who, by global standards, are young and well-educated, the North American advantages are real. The business community is there. But just as with the original vision for NAFTA, political leadership is essential.

That political leadership was demonstrated this week in Mexico City. Joe Biden got it right when he repeated Justin Trudeau’s words: “When we work together we can achieve great things”. As always, the test is in the follow-through. All three leaders have secure mandates for at least another couple of years. Let their motto be, per the famous Second World war memo from Bletchley Park to Winston Churchill, “Action this Day’’.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a Fellow and Senior Adviser with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.