The Starmer Storm: How Labour Got Smart, and Lucky

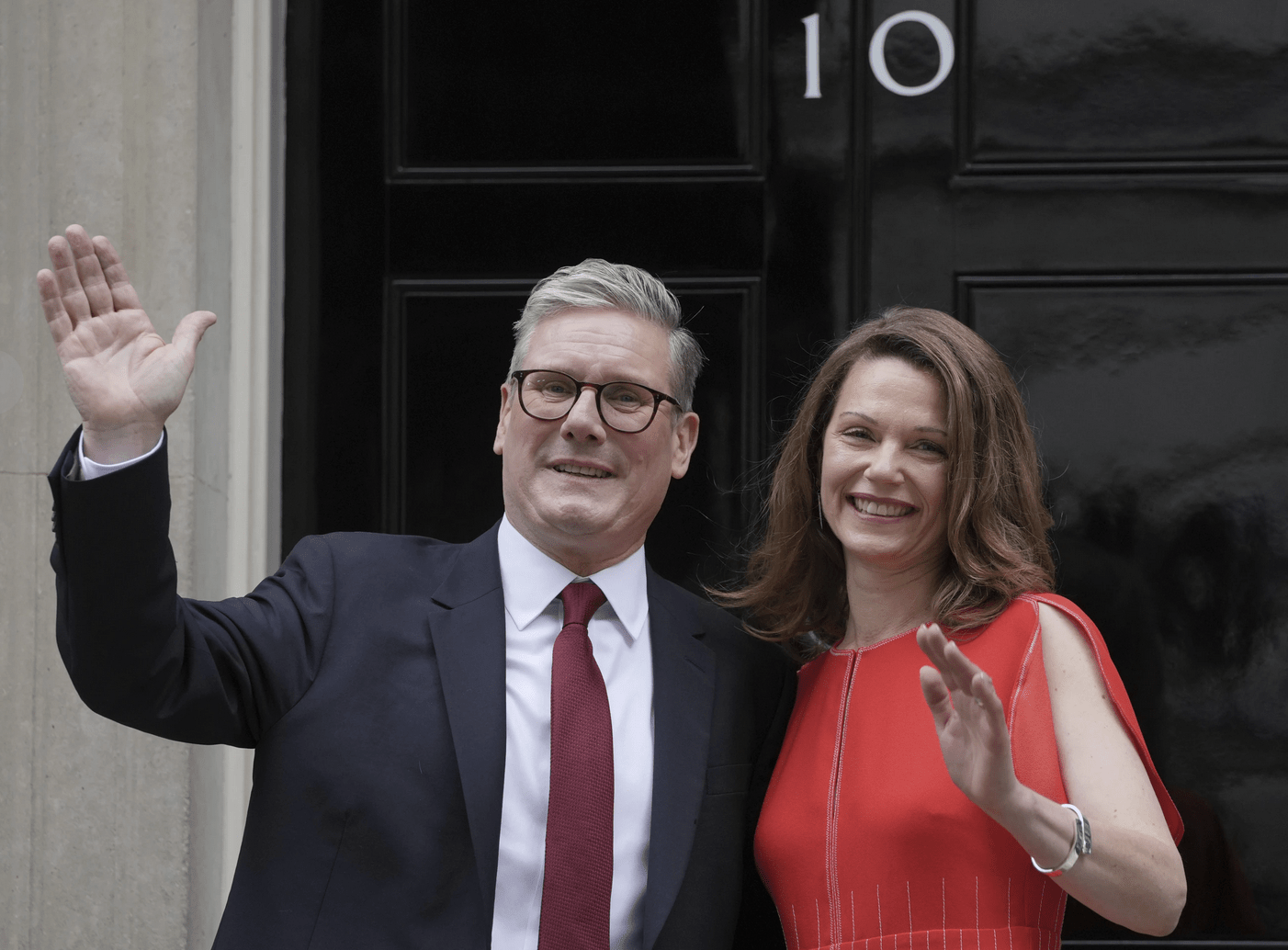

Newly elected UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer and Victoria Starmer on Friday, July 5, 2024/AP

Newly elected UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer and Victoria Starmer on Friday, July 5, 2024/AP

July 5, 2024

“We Did It!”

That’s the mood here in England, the morning after the Labour Party achieved one of the most spectacular turnarounds in the history of democratic elections, winning 412 seats of 650, up from 203 in 2019. The Conservatives went from 365 in 2019 to 121.

So, the Brits have ousted the Conservative government after 14 years. In 2010, David Cameron had ended 13 years of Labour government. In 1977, Tony Blair ousted the Conservatives under Margaret Thatcher and John Major for 18 years. A pattern of cyclical disenchantment, one that apparently takes more than a decade to set in.

It looks, superficially, like a normal change of hands from one of the two governing parties to the other. “Nothing to see here. Move along.” That is what the markets say this morning. Despite hyperbolic predictions by Rishi Sunak and the Conservative campaign that Labour would ruin the country, the pound is steady.

For the British people, it is emphatically a rejection of the Conservatives, who are widely believed to be the ones who “ruined the country.” Their vote since 2019 plummeted by more than 20%.

Beneath this surface outcome, there is a lot to see, with possibly problematic implications for the future.

Credit Keir Starmer first for “doing it.” He is only the second leader in history to win more than 400 seats. The first was Tony Blair, whose 1997 landslide of 418 seats for “New Labour” was preceded by Blair’s re-positioning of his party toward the centre, to make it a more believable winning proposition. It was also Blair’s conviction that democratic governance is managed from, and through, the political centre, which is where compromise lives.

Starmer has done a comparable job of internal rebuilding and reform. It is all the more remarkable because in 2019, under throwback leftist firebrand Jeremy Corbyn (who won his seat last night as an independent), Labour was buried by Boris Johnson’s landslide. Johnson won historically Labour constituencies behind “the Red Wall” in blue-collar towns in the North, where voters had largely voted “Leave.” At the time, based on historical precedents, it was believed that Labour would be out of office for a decade. After succeeding Corbyn as leader, Starmer cleaned house in the party, moved it back toward the centre, and imposed party discipline, using a no-drama professional style to reassure voters that Labour was low-risk. It was called the “Ming vase strategy” to protect their 20-point polling lead, walking tenderly on a slippery floor to avoid a misstep.

Determined to win back Red Wall deserters, Starmer resisted pressures to seek reversal of Brexit. A small group of visiting Canadians met in London with Shadow Foreign Minister David Lammy in December, 2022, when polls were indicating the British public had already decided that Brexit was a “mistake.” He confided Labour would not make Brexit an issue in any way, that it was politically “over and done with.” They needed to get the Red Wall Brexit voters back from the Conservatives.

During the campaign, Starmer resisted the notion his government would, if elected, petition the EU to rejoin at least the single EU market or a full customs union. It half-worked: the Red Wall Labour voters left the Conservatives but seem to have migrated instead to Nigel Farage’s populist right “Reform” (formerly the UK Independence Party). Reform’s popular vote rocketed to 15%, enabling Labour to win this vast national majority of parliamentary seats with only 35% of the national popular vote, a historic low for a new government. Reform only won 4 seats with 15%, while with a slightly smaller popular vote (13%), the Liberal Democrats won 71 seats. Expect a renewal of damning criticism of the equity of the first-past-the-post system, and a call for proportional representation. It’s unlikely, as in Canada, for the beneficiaries of the system to change it. But to their credit, both Labour and the Liberal Democrats won so big, because of the efficiency of their votes – they got the votes they needed where they needed to get them.

So, Starmer did it. But he couldn’t have done it if the Conservatives had not cooperated by doing themselves in.

Campaigns do matter. What mattered this time was that the Conservative campaign was inept without precedent. Their leader, their fourth Prime Minister since 2019, was a poor choice by out-of-touch Conservative Party members to replace the disgraced 45-day Prime Minister Liz Truss they had chosen to replace the amply disgraced Boris Johnson. Sunak is a decent person, smart on the things he knows (private equity, etc), but political skill is not one of them.

So, Starmer did it. But he couldn’t have done it if the Conservatives had not cooperated by doing themselves in.

Just two anecdotes to illustrate: on May 22, when polls were indicating Labour retaining the 20-point lead held ever since the Liz Truss debacle in 2022, Sunak stepped out in front of 10 Downing Street to announce a snap election. It was pouring rain. Sunak, very, very wealthy, a smart dresser who wears bespoke suits and designer shoes beyond imagination from behind the Red Wall, spoke earnestly about needing an election to provide the British with the future they deserve. As he did so, the rain poured down his face. His suit turned shiny. The amplified music from a daily protest demo from a few blocks away partly drowned him out. Everybody who knows anything about staging asked themselves in horror, “what in God’s name persuaded his handlers to send him out without an umbrella, at least, or better, to use the inside media briefing room Boris Johnson had built?” There is no answer to the question. It simply defined the way his campaign was going to go — establishing a sense of doom early on, conveyed by the candidate himself. They didn’t know what they were doing.

On the last day, he made a defining statement that typifies their confusion. He declared complete confidence he would still be prime minister today, polls showing the enduring 20 point gap notwithstanding. Then, in his speech’s second part he urged voters to deny Labour the “super-majority” they seemed to be headed for. The juxtaposition made no sense.

Sunak never had a chance because the election was not going to be over his imagined future. The public was consumed with anger over the 14 years of the Conservative-run recent real past. They wanted the government out and gone.

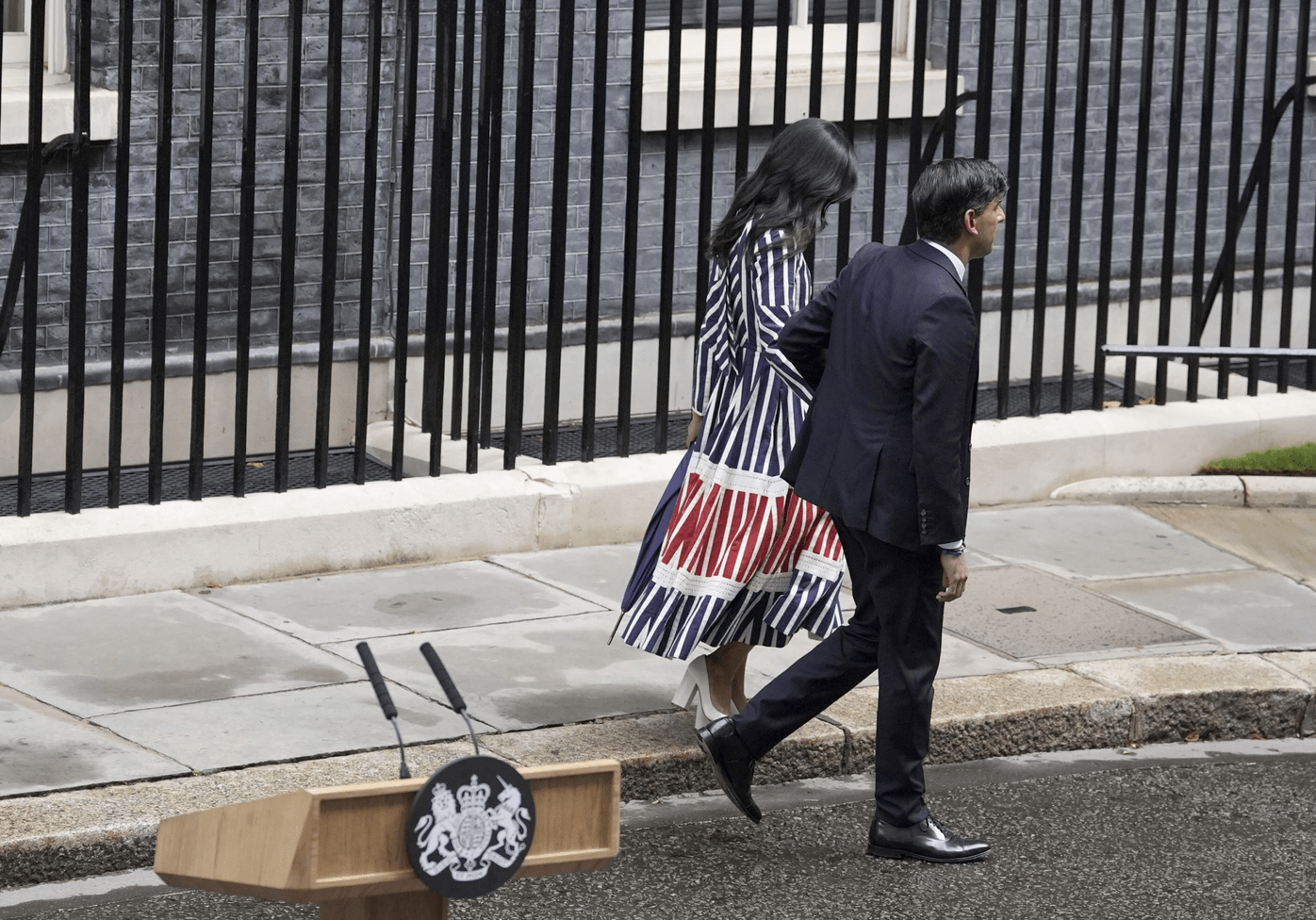

Outgoing Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and his wife, Ashkata Murty, leaving Number 10 on Friday, July 5, 2024/AP

Outgoing Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and his wife, Ashkata Murty, leaving Number 10 on Friday, July 5, 2024/AP

In those 14 years, so much happened, beginning with Cameron’s blunder in calling for the polarizing referendum on Brexit to appease the Tory nationalist right-wing. The right-wing scuttled successor PM Theresa May’s effort to find a reasonable accommodation with the EU, Britain’s largest economic partner. The ascent of lead Brexiteer Boris Johnson, the trauma of COVID, Johnson’s immature and dishonest comportment and expulsion, followed, and then the bizarre Truss interlude. During that time, UK numbers deteriorated: inward migration soared, as did hospital waiting lists, child poverty and hunger, housing costs, and inflation. GDP per capita was down 2019-23 (Canada, though did worse).

Over his 18 months, Sunak stabilized the public mood, and the economy, but he couldn’t excise public memory. To compress this analysis, I’ll draw from an e-mail just now from a smart, devoted Conservative: “People could not vote Tory because of Boris, Liz Truss, so the election was lost before Rishi became PM and then it was worsened by blue on blue fighting (and) plotting against Sunak from within – these are the people I am most angry with not the electorate, so in tennis terms the conservatives made a continuous series of unforced errors – no wonder we lost.”

Twelve cabinet ministers lost their seats, a record. The rejection of the last 14 years is clear. All Tories are held responsible. But which way will they go now? Most of Reform’s 14% of voters had been theirs last time. Some will argue the Tories should now move to the nationalist right to compete. But some of the Tory right’s most fractious disrupters lost their seats. Many others will urge the party to move toward the centre instead, with clearly competent people, under a leader like ex-Chancellor Jeremy Hunt.

Britain’s default political trait is Oxford Union glibness. It influences UN conferences and media. But the British seem tired of it. Starmer may be the answer

Nigel Farage, leader of Reform, who wants to poach the Conservatives, describes Reform’s sudden burst this morning as, “The first step in something that it is going to stun you.” That’s what he does, a B.S. artiste par excellence, but, like Mélenchon in France, and his idol in the US, Trump, there are a lot of people who like his divisive and angry lines.

So, what about Starmer and the future?

He didn’t shine in debate, especially when Sunak was aggressively interrupting and making unfounded accusations that Labour would raise taxes.

But he’s cogent, obviously tough and will run a disciplined government. As former chief prosecutor, he has done important things. It is to his credit with the politician-fatigued public, that he is not a lifer in politics like David Cameron, or a public blowhard like Johnson or Truss.

Britain’s default political trait is Oxford Union glibness. It influences UN conferences and media. But the British seem tired of it. Starmer may be the answer, if he provides substantive delivery on housing, social care, and growth, on which he is staking his success.

He is inheriting a huge set of challenges, which could be summed up as crummy performance on services from health to schools to trains and infrastructure, flat productivity, diminished inward investment, a wobbly financial balance sheet, and most of all, public disaffection and widespread distrust.

Rare among politicians, he is an incrementalist, and avoids grand proclamations of policy intention. He’ll have a good team. The markets love financial safe hand Rachel Reeves, the incoming Chancellor. Best for him, his majority is so large that he can fend off pressures from his left wing.

Internationally, he’ll be added value, including for Canada as a key like-minded and multilateral partner, especially if Trump does win, since the UK will be in the same diplomatic boat as we are. Starmer won’t repeat sucky pilgrimages to Washington to win Trump’s mercy, though on military issues, the Brits and the Yanks will still be bosom buddies.

Lots of international commentary holds that Labour’s win is a positive contrary signal to the rise of the ultra-nationalist and populist right in Europe. Sort of true, but Britain is a moderate country politically. Sunak’s resignation speech just now, Friday morning, characteristic of the man in its courtesy, generosity to Starmer, and emphasis on “Kindness, decency, and tolerance” says it all. The extreme right, Oswald Mosely aside, has never shone here. However, watch out for Farage, who is irresponsible and utterly destructive.

So, a big election is over. Will public trust return? This was the lowest turnout for ages. If not, fear turbulence of the kind that is roiling Europe and the US. Our elections are increasingly about what or whom the people don’t want. The new Labour government already faces issues in Ireland where Sinn Fein, the Republican dissident party, beat the Unionists. In Scotland the SNP was battered, but because few were happy with it. On the other hand, the Green Party did well in the UK, because of what they clearly stand for. And at 10 Downing, as a sign of stability and continuity, Larry the Cat is staying on for his fifth PM. On the other hand, he is 18.

If this qualified landslide signals one thing primarily, it is to confirm that for incumbents everywhere, beware of the people’s wrath. Once the mood moves to “time’s up,” it is irrevocable: governments need to change leaders or go under. But for God’s sake, North American readers, choose the right one.

Contributing Writer Jeremy Kinsman served as Canada’s Ambassador to Russia, Italy and the European Union and as High Commissioner to the UK. He is a Distinguished Fellow of the Canadian International Council.