The Social Determinants of Dementia: Canada Needs Collective Action to Prevent a Public Health Crisis

Alzheimer’s Society of Canada

Alzheimer’s Society of Canada

By Stéfanie Tremblay

May 22, 2024

Dementia is a debilitating condition that currently affects more than 750,000 adults from all Canadian provinces, their caregivers, and society as a whole due to its impact on the health care system and the economy. With an aging population, the number of Canadians living with dementia is expected to rise dramatically — more than double, to 1.7 million people by 2050 according to the latest Landmark Study from the Alzheimer Society of Canada.

While there is currently no cure for dementia, there are risk reduction strategies that can be implemented to slow down this rise by delaying, or even preventing, the onset of dementia. Even delaying the onset of dementia by as little as a year would make a massive difference in the number of new cases, which would alleviate the burden on caregivers, the health care system and the economy. While some actions can be taken by individuals to reduce their own risk of dementia, a population-level approach would likely have a greater impact on the total burden of dementia in Canada.

Canada has developed a national strategy for dementia in response to the WHO Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia. This strategy articulates principles and main objectives that should guide the actions of governmental, non-governmental, and community organizations working on dementia. Prioritizing a population-level approach (area of focus 2.4 of the national dementia strategy) to prevention is essential to ensure that the human rights and diversity principles set out in the national strategy are respected.

Risk factors for dementia

The dementia public health crisis is often seen as the inevitable product of an aging population. While age is a major risk factor for dementia, it is also a non-modifiable one, as are sex at birth (females are more at risk) and genetics. However, there are several risk factors that can be acted upon. Modifiable risk factors include many lifestyle habits such as physical activity, diet, tobacco and alcohol consumption, exposure to air pollution, and social and cognitive activities. Treating health conditions that predispose to dementia (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, depression, and hearing loss) is another way to reduce risk. New research also suggests oral health may be an important determinant of brain health with conditions like periodontitis increasing the risk of dementia.

Although these risk factors are deemed modifiable, an individual’s ability to address them largely depends on their context – the environment in which they live and work and the resources available to them. In other words, modifying these risk factors is not equally accessible to everyone. “These risk factors are only truly modifiable if the proper supports are provided by our communities, public health agencies and other governmental organizations,” per The Many Faces of Dementia in Canada, the 2024 Alzheimer Society of Canada’s Landmark Study/Volume II.

Disparities in risk factors and dementia prevalence

People of certain communities experience dementia at a higher rate than others. For instance, there is a higher prevalence of dementia in ethnic and cultural minority groups, such as Black people and Indigenous people in Canada. Risk factors for dementia such as diabetes, physical inactivity, and obesity are also more prevalent in Latin American and Black individuals. These disparities likely arise from a complex combination of factors including genetic factors, socio-economic status, and experiences of racism and discrimination, or as they’ve been characterized by pioneering UK health and inequality researcher Michael Marmot among others, the social determinants of health.

Together, these factors impact a person’s stress levels, which negatively affects their health, as well as their ability to address their modifiable risk factors, and their ability to access, and propensity to seek, proper care. For instance, people of lower socio-economic status are more likely to live in polluted or dangerous environments that are not conducive to active living habits such as biking and walking. They may also have limited access to healthy foods due to their cost and unavailability in their neighborhood.

People of ethnic and cultural minorities are also more likely to delay care-seeking, limiting the potential for prevention through treatment of predisposing conditions (e.g., hypertension and diabetes). Several barriers to health care exist and can include financial inability to access services that are not covered by the public system (e.g., dental care, psychotherapy, physiotherapy), in addition to cultural barriers and systemic racism, which can impact the quality of care received.

The Landmark Study estimated that people of ethnic minorities, Indigenous people, and women will continue to be disproportionately impacted by dementia in the next 30 years, and that the gap will grow even wider if no actions are taken.

Risk reduction strategies

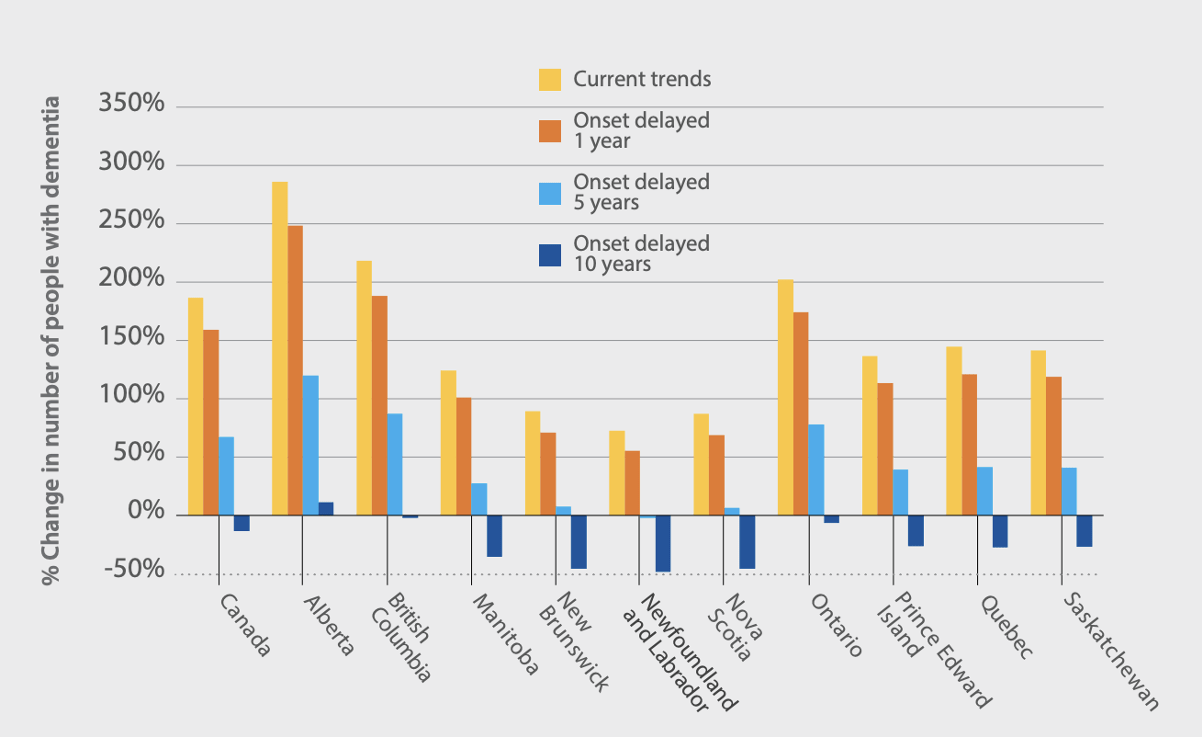

Successfully implementing risk reduction strategies has the potential to delay the onset of a large number of dementia cases in Canada (see figure below). Even a 1-year delay would meaningfully slow down the projected increase and would mean fewer people receiving a dementia diagnosis every year in all Canadian provinces. But we can aim for more. Research has already shown a 5-year delay is possible through a risk-reduction strategy involving only cognitive activity. If we utilize intervention strategies that act simultaneously on several risk factors, delaying dementia onset by 10 years may not be out of reach. This would slow down the projected rise in cases to such an extent that it would result in a reduction in the number of people living with dementia in 2050 compared to 2020.

Change in the number of people with dementia in 2050 relative to 2020.

Change in the number of people with dementia in 2050 relative to 2020.

Source: The Alzheimer Society of Canada (2022). The Landmark Study – Navigating the path forward for dementia in Canada.

If we hope to significantly reduce the overall burden of dementia in Canada, we need to tackle this public health challenge with a population-based approach. This approach aims to reduce the risk of everyone across society by adopting policies that make healthy behaviour the option that is more convenient and accessible, resulting in unconscious behavioral changes (e.g., eating healthier because healthy options are more available and accessible in a neighborhood).

Focusing only on individuals considered at high risk would have a limited impact for several reasons. First, because dementia and its risk factors are extremely common in Canada, risk reduction interventions must be applicable to a very large number of people. Further, since dementia occurs as a result of accumulated exposure to multiple adverse factors throughout life, strategies that aim at improving the living conditions of a whole population (which would reduce exposure to risks at all stages of life) are more likely to significantly impact dementia incidence.

Lastly, since dementia and its risk factors are strongly linked to socio-economic status, it’s important to adopt an approach that aims at reducing inequities. An individual-level approach that focuses solely on promoting healthy lifestyle habits could actually increase inequalities in dementia incidence because people of higher socio-economic status, and with other forms of privilege, would be more likely to be able to adopt these behaviors (e.g., eating healthy foods because you can afford it). A population-based approach would therefore be a fairer strategy that respects the rights and dignity of all Canadians, in addition to having a more far-reaching impact on dementia prevalence in Canada.

The way forward

While some progress has been made in risk reduction over the past 4 years (especially in reducing the prevalence of dementia risk factors such as drinking, less education, hypertension, and smoking), more needs to be done to ensure that the most vulnerable people in Canada benefit from this progress. Decision-makers can help shape the future for our aging population and our society by working on these three aspects:

- Strengthening the public health care system: Improving access to primary care, expanding coverage to include more services (e.g., dental care, nutrition, physiotherapy, mental health resources), and addressing racism and discrimination in care settings.

- Increasing the accessibility of health-promoting behaviours: Supporting municipalities in making health a priority in urban design (e.g., increasing the amount of green spaces, gathering places, bike paths, and outdoor sport facilities), reducing the accessibility of unhealthy habits (e.g., imposing a limit on the number of fast-food restaurants permitted), subsidizing access to sport facilities for people with lower income, and lowering the cost of healthy foods such as fresh fruits and vegetables are some examples.

- Addressing inequities: Reducing the daily manifestations of economic inequality that contribute to risk factors, e.g., increasing minimum wage, improving housing accessibility, implementing programmes aimed at reducing poverty, tackling systemic racism and discrimination, and prioritizing early childhood development, among other social determinants.

If, per current projections, 1.7 million Canadians will be living with dementia by 2050, the impact on caregivers — often family members who spend an average of 26 unpaid hours of care per week — and on the economy will be enormous. The economic burden from lost labour is estimated at $7.3 billion, the equivalent of 235,000 full-time jobs, and this number is expected to triple by 2050. Action is urgently needed to slow this rise in dementia cases and limit its impact on society. Dementia will affect everyone. Not only those who will develop the disease, but also their loved ones, their caregivers, the workforce, and our economy. We need to act now, and we must do so collectively.

Stéfanie Tremblay is a doctoral candidate in medical physics at Concordia University. Her current research focuses on uncovering early biomarkers of declining brain health in individuals at risk of dementia using MRI. She hopes to contribute to developments in policies that aim at improving brain health for all Canadians.