The Remarkable Life of Supreme Court Justice Michel Bastarache

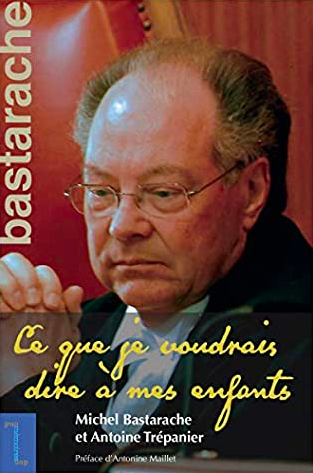

Ce que je voudrais dire à mes enfants

University of Ottawa Press/December 2019

Reviewed by Stéphanie Chouinard

December 14, 2020

In the upper levels of Canada’s political institutions, the Supreme Court easily ranks among those whose secrets are the best guarded. For this reason, every time a former justice publishes a memoir, it is a formidable opportunity to learn more not only about their life, but also about the court and the other justices on the bench.

Michel Bastarache’s autobiography (written with journalist Antoine Trépanier and published in French in 2019), Ce que je voudrais dire à mes enfants (What I wish I could say to my children), offers us one such rare insight into Canada’s highest court. However, what’s even more striking about this book is the open window it grants the reader into what Bastarache calls the “failure of [his] life” – that is, the premature deaths of his two children. This is a little-known fact about Bastarache, who, before the memoir, was notoriously private and reticent to talk about himself. This profoundly sad event is ubiquitous in the memoir, which is epistolary in fashion, written as a letter to Jean-François and Émilie, who died decades ago at 3 and 17 years old, respectively, of an incurable nerve disease.

Before delving into his own life, Bastarache begins by recounting his father’s ascent from a modest family in New Brunswick to becoming a doctor in Québec and eventually returning home to practice in Moncton, where Bastarache was raised. Growing up in a province in linguistic turmoil and in a proud francophone family marked his childhood and anchored his sense of social justice. His sense of belonging to Acadie and his will to fight for the rights of his people is a thread throughout the book. He recalls the election of the first Acadian premier, Louis-Joseph Robichaud, and the adoption of the federal and provincial Official Languages Acts, in the 1960s, as defining moments in his childhood: “From this moment on, an extremely clear message was sent to me: anglophones and francophones are equals and must therefore be treated equally. I did not forget it.” It’s a point that not only will he convey time and time again in his career choices and, as a judge, his rulings, but that will resonate with Canadians who belong to minority language groups across the country.

The portrait of the early Bastarache is of a young man who is more serious than many of his peers, and who finds friendships difficult. He recounts his studies from Moncton, to Montréal, to France, after which he eventually comes home to become a professor at Université de Moncton. This is when he begins investing himself politically with language-rights civil society organizations, such as the Société nationale de l’Acadie and the Fédération des francophones hors Québec, which he helped found. He also recounts the drafting of Bill 88, which was adopted by the Richard Hatfield government in 1981, as well as his mandate at the helm of the Poirier-Bastarache commission on official languages, which saw Bastarache receive death threats. He also discusses his time spent working with insurance company Assomption Vie, as well as pleading before the Supreme Court in the language rights landmark Mahe case opposite John C. Major, who will later be a colleague and a friend on the bench. He shares his thoughts on the relationship he had with other colleagues at the court, and some major cases he heard, such as the Quebec Secession Reference. He also addresses some of the mandates he took on upon retiring from the court, such as the Commission on the Québec judicial appointments process which, looking back, he bitterly regrets accepting, as well as a conciliation and compensation process he oversaw for victims of sexual abuse by members of the clergy in the Diocese of Bathurst.

The autobiography is interspersed with glimpses of the difficulties Bastarache and his wife, Yolande, faced at home with their two sick children. Bastarache admits to drowning himself in work to avoid having to think about Jean-François and Émilie. It is a profoundly human story told by a man who lived quite an accomplished life, making history as the first Acadian Supreme Court justice, and who continues to contribute to Canadian public life, as demonstrated by his scathing report on sexual misconduct in the RCMP, recently released.

Ce que j’aurais voulu dire à mes enfants is a fascinating read, a biography that should be of much of interest for Canadian politics and law scholars as well as for anyone interested in language rights in Canada.

Contributing Policy writer Stéphanie Chouinard is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Royal Military College (Kingston), cross-appointed at Queen’s University. Her research focuses on language rights, Indigenous rights, federalism, and judicial politics.