The Quiet Canadians: Stories from Two Decades of Diplomacy in Indochina

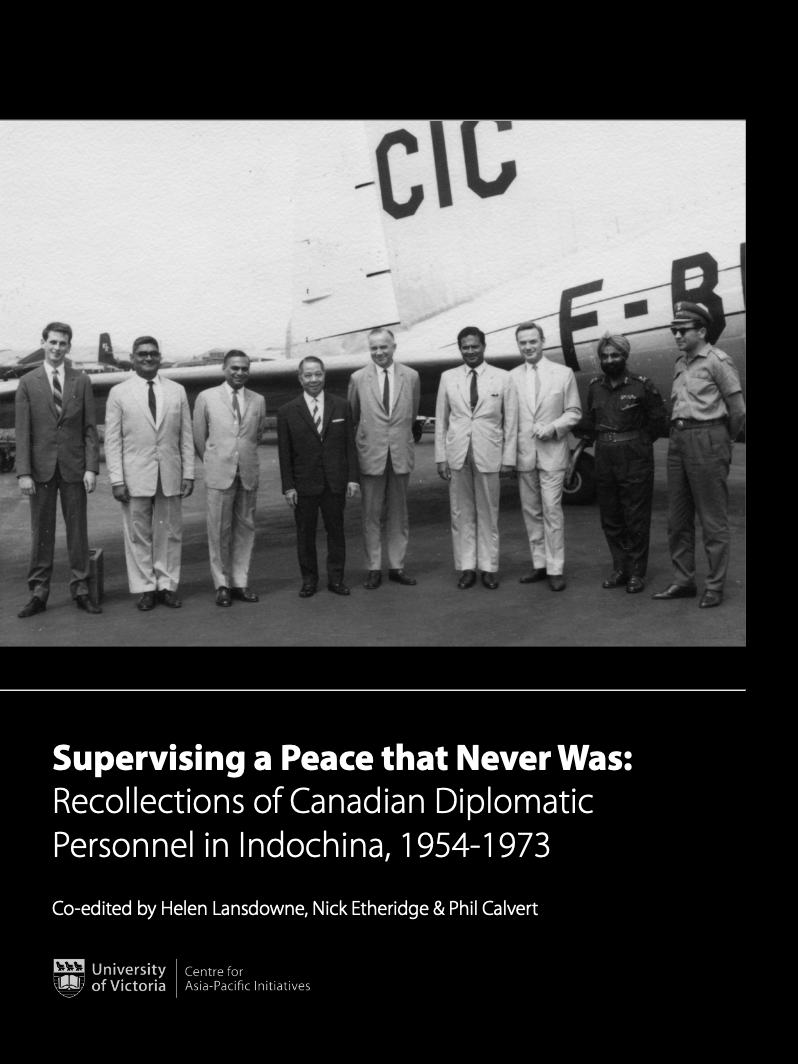

Supervising a Peace that Never Was: Recollections of Canadian Personnel in Indochina, 1954-1973

Edited by Helen Lansdowne, Nick Etheridge & Phil Calvert

University of Victoria Centre for Asia-Pacific Initiatives/2023

Reviewed by Colin Robertson

February 11, 2024

Supervising a Peace that Never Was: Recollections of Canadian Diplomatic Personnel in Indochina, 1954-73 recounts life in what is now a mostly forgotten chapter of the kind of quiet diplomacy and ‘helpful fixing’ that once characterized Canadian foreign policy, in this case over the two decades when a third of Canada’s foreign service and almost 2000 troops served on the International Commission for Supervision and Control (ICSC-Vietnam) and its successor, the International Commission of Control and Supervision (ICCS).

Published open source (download for free) by the Centre for Asia-Pacific Initiatives (CAPI) at the University of Victoria, Supervising a Peace that Never Was is co-edited by CAPI Associate Director Helen Lansdowne, and former foreign service officers Nick Etheridge and Phil Calvert, who both served in multiple postings in Southeast Asia.

In this mix of diaries, reminiscences and transcriptions from oral interviews, the thirteen contributors are by turns funny, poignant and engaging in their reflection of everyday diplomatic life during the tumult of the long conflict in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia.

In keeping with the famously fictionalized political complexity and diplomatic intrigue of the place and time, some of these tales read like a cross between Somerset Maugham and Graham Greene.

Nick Etheridge by the unusable Hanoi Villa bomb shelter, December 1972

Nick Etheridge by the unusable Hanoi Villa bomb shelter, December 1972

Nick Etheridge, who later served as our representative to Cambodia and as High Commissioner to Bangladesh, tells us about taking shelter in the storied Hanoi Thong Nhat hotel — the re-named Metropole, a local French colonial landmark that housed multiple UN agencies and embassies, now the Sofitel Legend Metropole — with Joan Baez, who would play her guitar to while away the hours during the Christmas bombing in 1973.

For secretary Anne-Marie Bougie who would serve in more than twenty other foreign assignments, it was endless trips to the airport while cycling through myriad states of mind — “laughter, downcast, insomnia, nonchalance, nervousness, nightmares, …loss of appetite” and “cultural shock…that was fortunately short-lived.”

If Hanoi was repressive, Saigon was anything but. David Anderson, who went out in 1963 and would later serve as Canada’s Environment Minister, joined a riding club, water-skied on the Saigon river and dated the niece of US Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge.

Family life with three daughters is evocatively captured by Eva and Fred Bild’s account of their posting in Vientiane, dodging bombs dropped during an abortive Laotian coup. Fred, who would later serve as our ambassador to Thailand and then China, had to be paddled to work on his first day because of flooding on the Mekong.

The backstory to the long Canadian Indochina assignment began at the 1954 Geneva Conference. The Conference aimed to settle issues following the Korean war armistice and the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu that ended France’s empire in Indochina. Supervisory commissions were to be established in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia to monitor the implementation agreements over the departure of the French, including prisoner exchanges. India would chair the commissions, with Poland representing the Soviet Bloc. Canada was asked to represent the West.

As Global Affairs Canada departmental historian Brendan Kelly writes in his erudite introduction to Supervising a Peace that Never Was, the request was “unexpected, unwelcome but unavoidable”.

“Unexpected” because we had marginal interests in French Indochina. Our delegation to the conference, led by External Affairs Minister Lester Pearson, had already left. Our interests were in Korea, where we suffered more than 1500 casualties.

‘Unwelcome’ because with a foreign service of 267, Canada was already stretched meeting the needs created by the proliferation of post-war multilateral organizations. Our Asian presence was slim: Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), India, Indonesia, Japan and Pakistan. The request would add, without notice, three embassies that together were the size of Washington, our largest embassy.

‘Unavoidable’ because of the pressure from our allies – the request came from British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden with support from the US and France. Participation also aligned with the St. Laurent-Pearson sense of multilateralism and our role as a ‘helpful fixer’ in another example of quiet diplomacy.

The first assignment of one Canadian diplomat posted to Paris during the Geneva Conference, writes Kelly, was to “find a good map of Indochina and to send it back to headquarters in Ottawa forthwith.” That lack of knowledge would soon change.

One constant theme is the frustration of the infrequent, inconclusive tripartite deliberations with our Indian and Polish partners on the ICSC. As Si Taylor, who went out in 1955 (and would later serve as deputy minister and ambassador to NATO and Japan) drily observes, “This was not rewarding work”. Still, Taylor’s reminiscences of his time in Vietnam capture the colour of diplomatic life amid living history. “Down the street from the Hotel Metropole, where we lived, was the Canadian mess, and that was a very popular social centre,” he recalls. “We had guests all the time. The most famous guest was Ho Chi Minh, himself. He came in his jungle suit and his sandals made of old rubber tires. Ho had great charm; he was a very sophisticated man.”

The official account of this period will soon be available in forthcoming Documents on Canada’s External Relations covering the Pearson and Pierre Trudeau governments’ Indochina experiences, including the peace missions of Blair Seaborn and Chester Ronning and the visit by Foreign Minister Mitchell Sharp that led to our withdrawal.

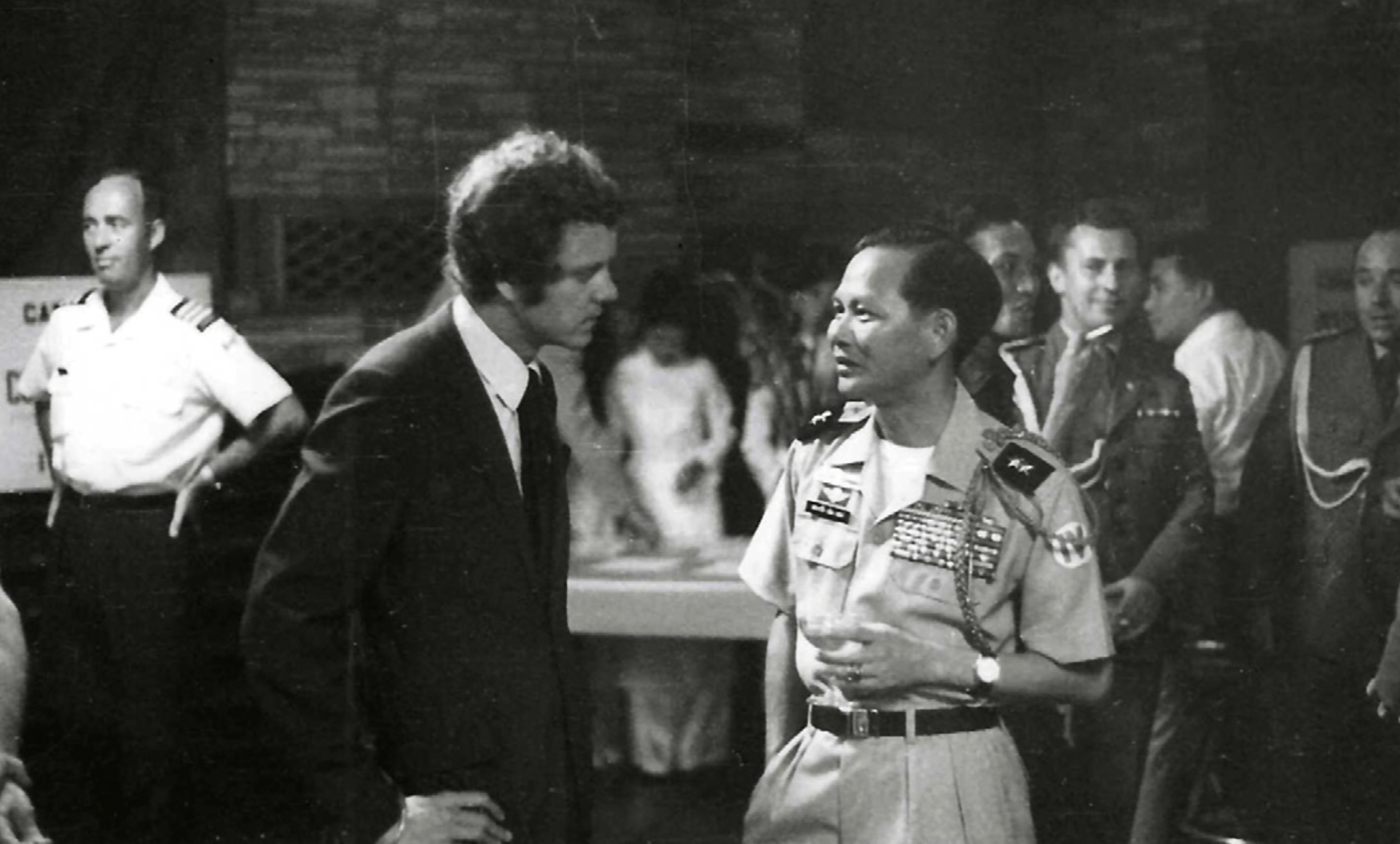

Manfred von Nostitz talking to South Vietnamese General Nguyen Van Nghi in Can Tho, 1973

Manfred von Nostitz talking to South Vietnamese General Nguyen Van Nghi in Can Tho, 1973

We already had experience in closing up the shop. When Prince Sihanouk tossed the ICSC from Cambodia in 1969, Manfred von Nostitz, who would later serve as Canada’s ambassador to Malaysia and Brunei, Pakistan and Afghanistan, then Thailand, took a sledge hammer to the cipher equipment, loaded it into a boat and dropped it in the Mekong River. He ran out of gas and had to paddle back to Phnom Penh to finish his “idiosyncratic ICSC assignments”.

Was our participation worth it? Opinion among those who served remains divided. We had gone in with few illusions, as the 1954 government statement announcing our participation made clear: “With full knowledge and appreciation of the responsibilities that will go with membership” and “no illusions about the magnitude and complexity of the task.” We suffered casualties. A Canadian diplomat and two members of our Armed Forces were killed when their plane went down, likely by a North Vietnamese missile.

The commission’s investigations were consistently stymied by the Poles, who would do nothing to impugn the Viet Cong or North Vietnamese. The Indians, especially after the 1962 war with China, saw a united Vietnam, even under the Communists, as another hedge against Beijing. So why rock the boat? It is, writes Taylor, “almost impossible to kill an international organization.” When it became apparent that the ICSC’s successor, the International Commission of Control and Supervision (ICCS), set up under the January 1973 Paris accords by which the US pulled its forces from Vietnam, would be as frustrating as its predecessor, Canada withdrew. Seventy years later, Canadians still serve on the United Nations Command (UNC) monitoring the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between two Koreas still technically at war.

The experience left those who served with few illusions about communism. As Taylor also observes, “We were not much for the fashionable ‘Jane Fonda’ view of North Vietnam”. It also created a skepticism about political leadership that espouses “rational, hard-nosed theory” that saw foreign policy as the “foreign extensions of domestic interest”. Taylor and his generation of realists, a good number of whom had also served during World War II, would remind us young officers that while planning was important, middle powers like Canada could never ignore former British prime minister Harold Macmillan’s response to the question from a young journalist of what troubled him most: “Events, dear boy, events.”

The Canadian experience developed deep, firsthand Asian expertise within our foreign service. As von Nostitz points out, this helped Canada develop a “respected Asia-Pacific architecture”, enabling the Canadian breakthrough to recognize China in 1970, becoming a founding dialogue partner of ASEAN, a member of the ASEAN Regional Forum security group, implementing innovative CIDA programs in Asia, establishing the Asia Pacific Foundation, and taking in more Indo-Chinese refugees per capita than any other nation.

That we subsequently let this hard-earned capacity shrivel is why the current government is now trying, through its Indo-Pacific Strategy, to re-establish a significant Canadian presence. To better develop their situational awareness of our earlier experience they would do well to read Supervising a Peace that Never Was.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a fellow and host of the Global Exchange podcast with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.