The Political Economy: Addressing Canada’s Complacency Trap

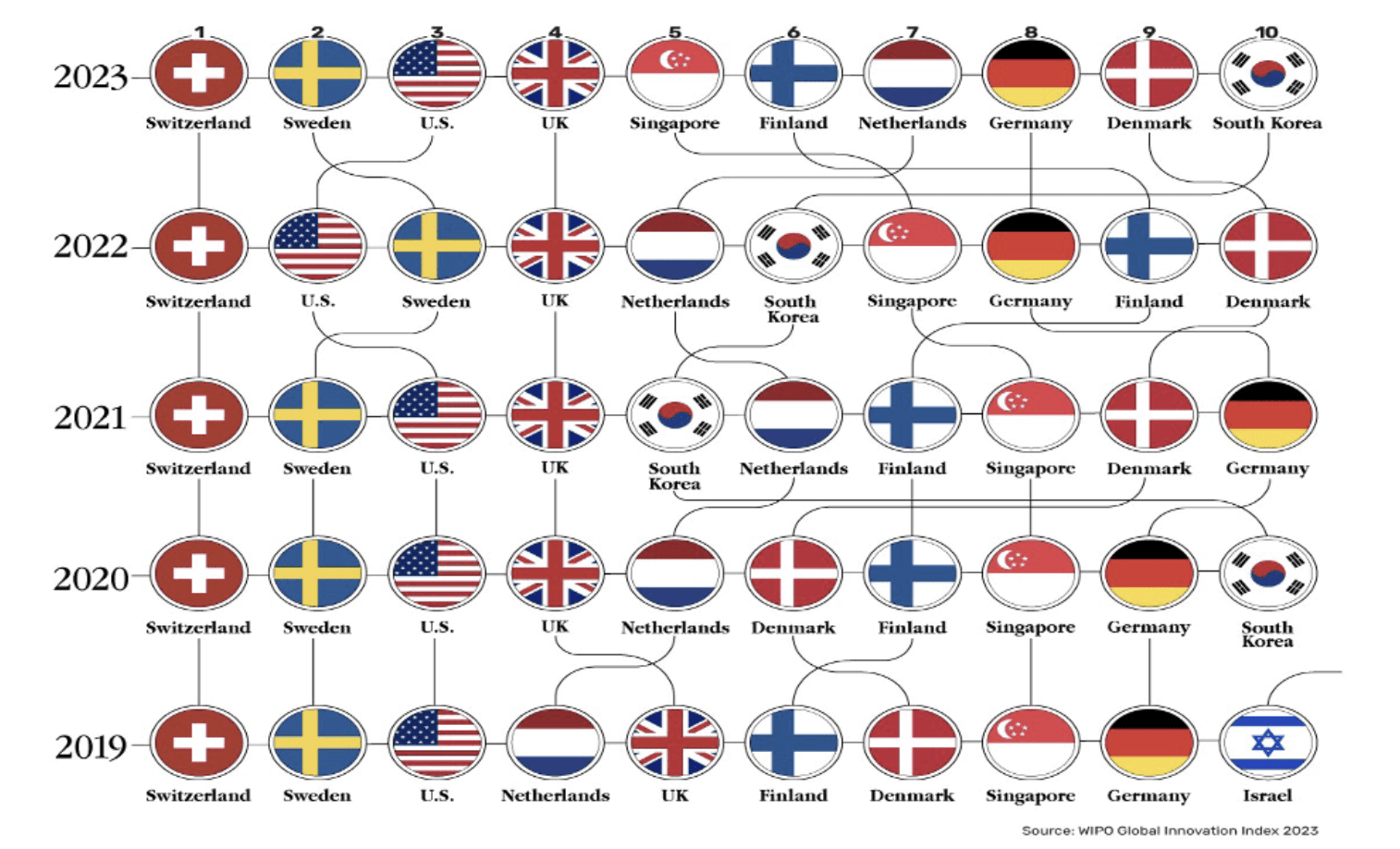

Top Global Innovators 2019-2023: a notable lack of Canada/WIPO Global Innovation Index

Top Global Innovators 2019-2023: a notable lack of Canada/WIPO Global Innovation Index

By Charles McMillan

June 19, 2024

In the third decade of this century, notwithstanding our political stability, high standard of living, and the geographical advantage that we share a southern border with an economic superpower, Canadians are exhibiting socioeconomic angst based on the high cost of housing, on inflation, on health-care wait times, and a real decline in incomes.

International agencies and domestic studies echo this national malaise, including low levels of national productivity and a weaker competitive position not only with Canada’s biggest trade partner, the United States, but with similar-sized countries elsewhere.

Productivity is not a one-off challenge. Too often, productivity is seen as a zero-sum game, between winners (governments and management) and losers (workers and citizens). In truth, productivity is a measure of national wealth creation, based on long-term national investments in infrastructure, new equipment, higher levels of worker training, and the adoption of organizational best practices and newest technologies. The fact that Canada has failed to address the issue is a sign that more trouble lies ahead.

Among peer countries, global comparisons provide signals of worrisome decline. The 2024 United Nations Human Development Index ranked Canada in 18th place among advanced economies, with an average income of $44, 500, behind such countries as Sweden, Australia, and Holland. The 2024 World Happiness Report, based on an international tracking of more than 130 countries, places Canada 15th — and 58th for happiness among young people worried about their prospects, in jobs, salaries, and living standards; among the older cohort, Canada ranks eighth.

Comparative rankings rarely tell the full story, nor does the political blame game, pitting workers against managers and owners of firms. For decades, Canada has put far too many resources – people, money, time – towards short term consumption policies and far too little in investment strategies, such as state-of-the-art green infrastructure and investment in talent. It is telling that in a survey of top universities, cited by scientists and researchers on measures like patent filings and article citations, Stanford leads the 46 US universities, with other countries following Germany (9), France (8), Japan, UK, and South Korea with 6, and Canada with only two.

Since 1867, Canadian prime ministers have focused on three main policy mandates: Federal-provincial relations, bilateral dealings with the United States and, depending on the era, national unity and Quebec. Today, given the knowledge revolutions underway, Canada has new priorities in a world of technological disruptions. Alas, federal and provincial budgets reflect a set of least-bad options, as determined by the party’s assessment of political advantages. In today’s political class, the currency is short termism and consumption measures (removing driver’s license fees in Ontario, costing a billion dollars, or pleas to weaken climate mitigation measures), illustrating a vacuous approach and invigorating the self-reinforcing spiral of the complacency trap.

In a world of knowledge workers and smart companies, many countries are devoting, sector by sector, attention to better incentives for investment – state-of-the-art equipment, new industrial processes, and easy-to-use software applications. In the rankings of STEM university graduate rates, Canada isn’t among the top 10 countries. Even in a traditional sector such as agriculture and food, Canada ranks only 10th in food exports, behind countries like Britain, Japan, and the Netherlands.

Without a retooling of priorities and an urgent mindset with less emphasis on short-term spending for consumption, leadership in all sectors – governments, the private sector, and universities – face an inflection point where warning signs are overlooked, amid a false sense of overconfidence that borders on quixotic.

More worrisome, the Canadian gap with the US for using state of the art new equipment is now over $9000.00 per worker, and so does weak corporate on-the-job-training programs. Canada’s private sector annual investment in science and innovation is well below one per cent of GNP, even as many global firms spend more per firm than Canada’s corporate sector. Canada commits only 1.6 of GNP, where most advanced economies have targets of 3.5-4.0 per cent of GNP.

Without a retooling of priorities and an urgent mindset with less emphasis on short-term spending for consumption, leadership in all sectors – governments, the private sector, and universities – face an inflection point where warning signs are overlooked, amid a false sense of overconfidence that borders on quixotic.

Unfortunately, Canada’s public discourse downplays how other countries are addressing competitive issues. In government, Canada’s policy processes are often removed from public concerns at large, and examples like Toronto’s spending on subway expansion from a budget set at $7b, now at $15b and counting, or the vast expenditures for outside consultants in Ottawa show a governance gap that seems unbridgeable. Further, entrenched productivity inhibitors such as interprovincial trade barriers, passive approaches to Canada’s crown corporations, lamentable processes for university commercialization, and protectionist regulation reinforce Canada’s complacency trap.

Presently, the relationship between policymaking inputs and outputs is not always clear. An unfortunate consequence is that good policy development becomes a casualty. Examples include systemic problems in health care. Despite all the promised investments and talk of improving efficiencies, Canadians still face long wait times and poor access to services while technology-based innovation is lackluster.

The 21st -century economy has reframed the private sector away from bulk-material manufacturing and processing of natural resources, based on conventional assumptions of diminishing returns – e.g. oil and gas, agricultural commodities, to new, scientific advances – fiber optic cables vs. copper, carbon fibers vs aluminum, advanced semiconductors vs. commodity chips.

Corporate performance benchmarks as well as university programs in Canada pay too little attention to novel approaches like corporate incubators, and the venture capital sector remains weak by global standards.

Canada’s higher education system also needs a serious reboot, including a new convergence between university and vocational training. Universities are a provincial responsibility and accept a system of perverse incentives – more body count, more provincial funding, weighted by undergraduate and graduate programs. Almost all have a 90-10 ration of UG-graduate programs, and with a few exceptions, administrators have opened the door to more foreign students, who pay higher fees, generating more revenues for salaries, new buildings, and too many commuter campuses and rising unfunded liabilities.

It is a little-known truism that most of the major public policy initiatives in Canada have a heritage of bipartisanship, so it is time to address Canada’s international competitive standing, and tone down the partisan rhetoric.

Policy success is a combination of doing things well and doing the right things. In a knowledge era, it is instructive to learn from Winston Churchill, who wisely said: “to improve is to change; to be perfect is to change often.”

Charles J. McMillan, Professor of Strategic Management at Schulich School of Business, is the author of twelve books and monographs, including The Japanese Industrial System and The Age of Consequence – The Ordeals of Public Policy in Canada, published by McGill-Queen’s University Press. His latest book, Precision Agriculture and Food Production: From Whence it Came and Where is it going? was published in 2023. Contact: charlesmcmillansgi@gmail.com