The NATO Vilnius Takeaway: Managing the Perils of a Small World

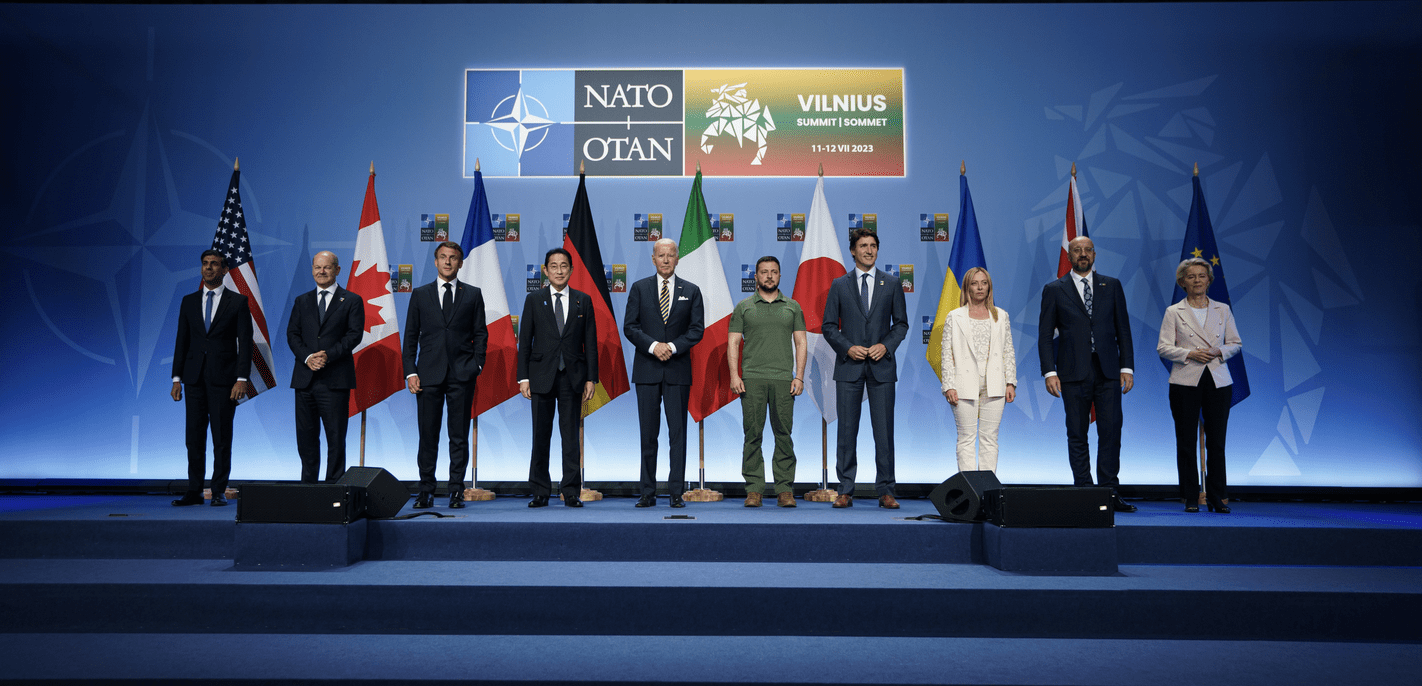

G7 leaders with Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky during the NATO Vilnius Summit/Adam Scotti

G7 leaders with Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky during the NATO Vilnius Summit/Adam Scotti

Colin Robertson

July 13, 2023

Alliances are hard things to keep together, especially when they work on the consensus principle. Four years ago, President Emmanuel Macron accused the North Atlantic Treaty Organization of being “brain dead”. Then came the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Suddenly, the Alliance, first set up in 1949 “to keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in, and the Germans down”, became relevant again.

This week in Vilnius, just 40 kilometres from the Belarusian border, NATO leaders reaffirmed “Ukraine’s future is in NATO…when Allies agree and conditions are met.“

Leaders also spelled out the ‘how and when’ of commitments made at last year’s Madrid summit. Other new security concerns, ranging from protecting undersea infrastructure to security challenges in the Arctic, were discussed.

Leaders endorsed a Defence Production Action Plan with the emphasis on readiness allowing for “deployability, interoperability, standardisation, responsiveness, force integration and support of our forces in order to conduct and sustain high intensity operations, including crisis response operations, in demanding environments.” The test, as always, will be in individual nations delivering on their action items.

China was also a focus. The communiqué accused China of deploying a “broad range of political, economic, and military tools to increase its global footprint and project power, while remaining opaque about its strategy, intentions and military build-up.” Noting the “deepening strategic partnership” between Beijing and Moscow and their “mutually reinforcing attempts to undercut the rules-based international order,” it called on Beijing “to abstain from supporting Russia’s war effort in any way.” “That said, the alliance remains “open to constructive engagement” with China.

The participation of leaders from Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea for a second year pointed to the organization’s evolving strategic direction around the growing recognition of China as a “security challenge”. Cooperation with the Indo-Pacific partners, especially on tackling hybrid operations, cyber defence and technology innovation will only increase.

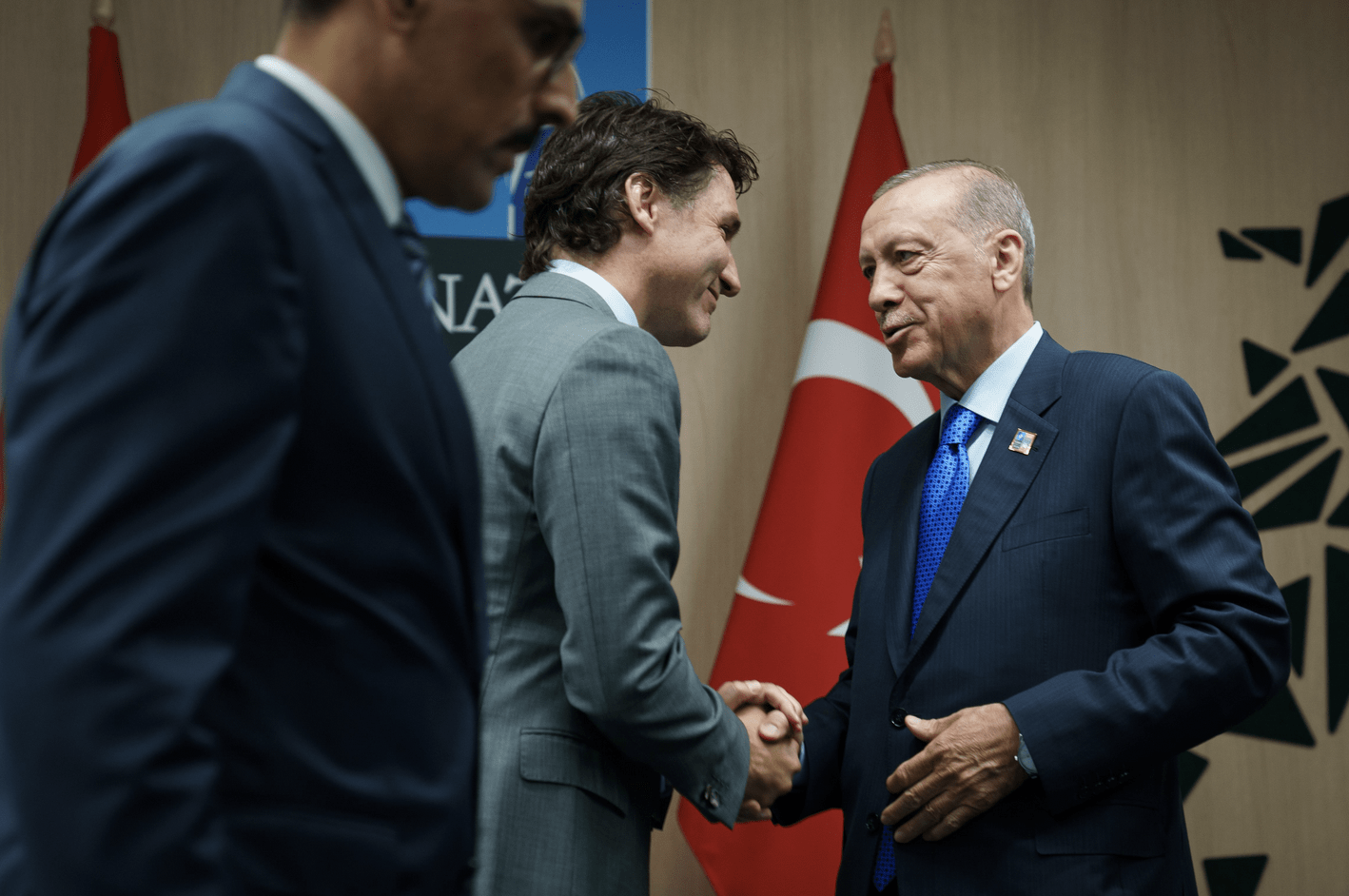

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan/Adam Scotti

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan/Adam Scotti

After months of rancorous delay, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan agreed to clear the way for Sweden to become the Alliance’s 32nd member. In company with Finland, which joined in April, NATO’s presence in the Baltic and high North is much more robust. The US said Ankara’s request for US-made F-16 fighter jets was not involved in Erdoğan’s changed position. Maybe. Erdoğan exercised his leverage and if that is the price of keeping Türkiye engaged and in the Alliance, then it’s a small price.

NATO is built around mutual security guarantees such that, per Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, an attack on one is an attack on all. It means that as long as the war goes on, Ukrainian membership would effectively put Canada and the rest of NATO at war with Russia. As President Joe Biden said, this is not going to happen.

President Volodymyr Zelensky was irked by the lack of immediate membership. It’s been 15 years since NATO leaders first pledged that Ukraine will become a member. Ukraine also has reason to be wary about guarantees. In 1994, the US, UK and Russia agreed to the Budapest Memorandum commiting them to keep Ukraine safe in exchange for Kyiv giving up its Soviet-era nuclear arms.

Yet, Zelensky did not leave Vilnius empty-handed.

According to the Kiel Institute, NATO members and partners had already committed in support of Kyiv about €165 billion; almost €9 billion for military aid.

Promising to support Ukraine “as long as it takes”, the G7 leaders at Vilnius pledged “specific, bilateral, long-term security commitments and arrangements” and other nations are encouraged to make their own bilateral guarantees.

A coalition of 11 nations, including Canada, will start training Ukrainian pilots to fly F-16 fighter jets. France joins Britain in supplying Ukraine with long-range cruise missiles. Germany finalized a 700 million-euro military aid package and the Alliance will continue with its Comprehensive Assistance Package. The new NATO-Ukraine Council held its first session.

Canada continues to give Ukraine significant support. We have welcomed more than 165,000 Ukrainians since the initial Russian invasion in 2014. Sanctions have been imposed on more than 2,500 individuals and entities in Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova. In return, Russia has sanctioned hundreds of Canadians. Since 2015, the Canadian armed forces have trained over 37,000 Ukrainian military. Since the February 2022 invasion, Canada has committed over $1.5 billion in military assistance to Ukraine, including eight Leopard tanks.

There had been talk of setting a 2 percent floor for NATO members’ defence spending. This will await the 2024 summit, the date set at the Wales summit in 2014 by which the 2 percent target is to be achieved. Eleven nations already meet the benchmark. Collectively, the Alliance recorded an 8.3 percent real terms increase in their defence budgets in 2023, the largest increase in decades.

Perhaps NATO finance ministers should join the regular meetings of foreign and defence ministers. Their goal should be fulfilling the obligations set out in Article 3 of NATO’s charter in which members commit “separately and jointly, by means of continuous and effective self-help and mutual aid” to “maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack.”

The US continues to carry the burden, covering two-thirds of NATO’s military spending. Observing that the “world has shrunk” Echoing themes of his February Warsaw speech, Joe Biden told students at Vilnius university that the Alliance has to step up together and build the broadest and deepest coalition “to strengthen and defend the basic rules of the road, to preserve all the extraordinary benefits that stem from the international system grounded in the rule of law.”

While Canada is not going to meet the 2 percent target, the PMO says we are on track to reach 32 percent of spending on equipment (the NATO target is 20 percent). Over the past year, Canada has committed more than $66 billion to national defence (a big chunk of this is for NORAD investments for continental defence).

Canada has led the eleven-nation NATO forward battle group in Latvia since 2017. Just before the Vilnius summit, Trudeau announced in Riga that, in line with commitments made at last year’s Madrid summit, Canada will double its troop deployment over the next three years to 2200 with 15 Leopard 2 A4M tanks and “procure and pre-position critical weapon systems, enablers, supplies and support intelligence, cyber, and space activities.” The Government has set aside $2.6 billion for what is Canada’s largest overseas mission. How this will affect the already-stretched capacity of our Armed Forces is to be determined.

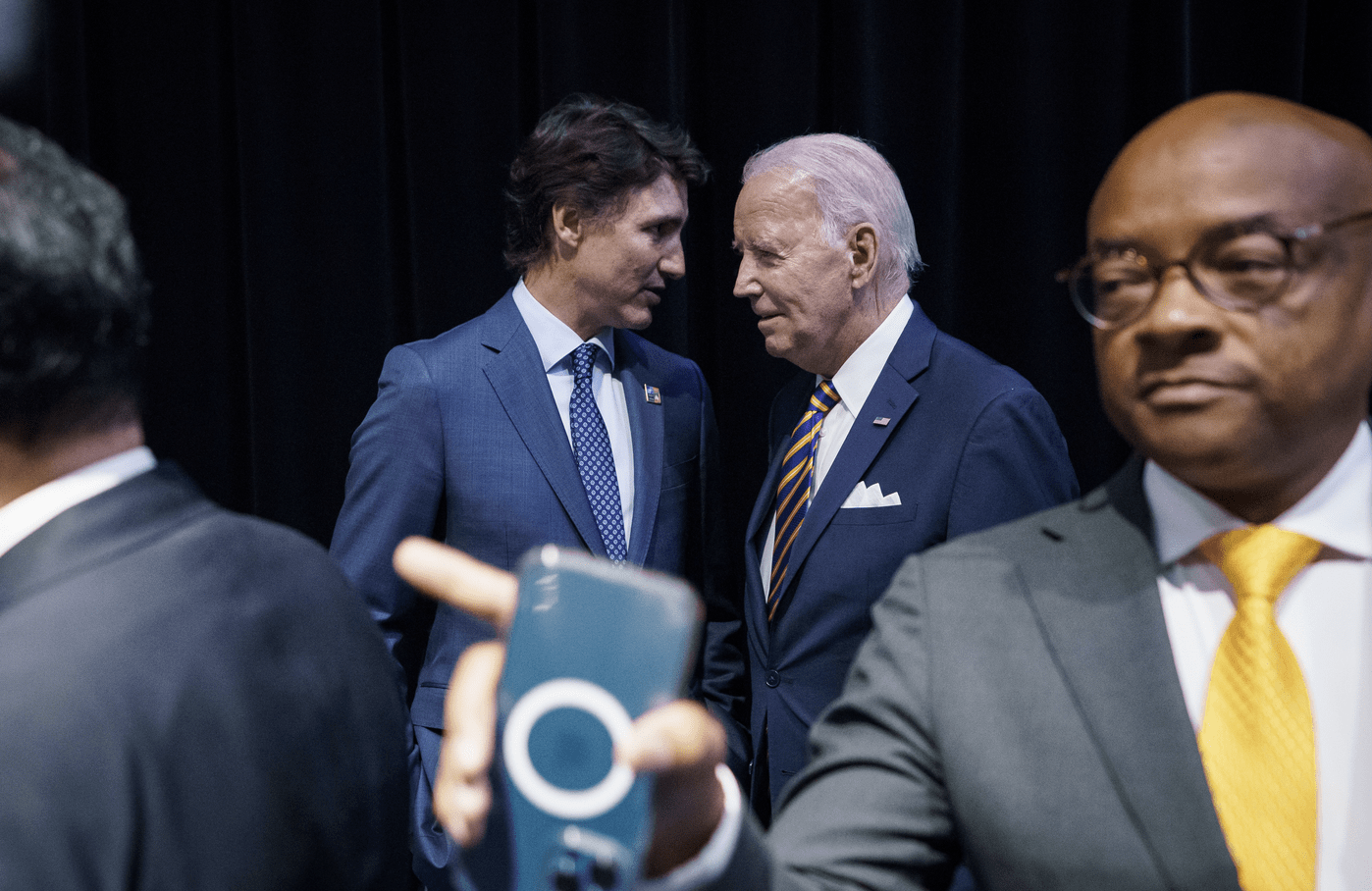

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau with President Joe Biden in Vilnius/Adam Scotti

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau with President Joe Biden in Vilnius/Adam Scotti

The American decision to provide cluster bombs got a lot of media attention but did not feature in the 11,000-word communiqué. Since 2008, more than 100 countries, including Canada, have signed the UN Convention on Cluster Munitions, which bans the use, stockpiling, and production of these arms. Neither the US, Russia, nor Ukraine are signatories to the treaty, and the weapons have already been used by both sides during the ongoing war.

In authorizing the delivery of the weapon to Ukraine, President Joe Biden told Fareed Zakaria: “It took me a while to be convinced to do it. But the main thing is, they either have the weapons to stop the Russians now … or they don’t. And I think they needed them.”

Under Biden, US leadership has revitalized the Alliance. Russia and China are threats but for the allies, including Canada, their abiding fear is a return of Donald Trump in next year’s presidential election. Trump has threatened to leave NATO and end the war “in 24 hours”.

Alliance members have wrestled with the morality of providing weapons to Ukraine from the outset. The wrestling, now over fighter jets, will continue. It’s a reflection of western values that do not trouble the autocrats.

Alliances of democracies are difficult. Division in opinion is natural, if frustrating. They are slow to act especially when consensus is the operating norm. But as we saw at Vilnius, they are capable of decisions that will strengthen the deterrence that is vital to our security.

For Putin, Vilnius was a setback. The argument that Putin has an incentive to keep fighting now that he knows that Ukraine stays out of NATO as long the conflict continues is weak. Ukraine is fortified and will remain so “as long as it takes”. The Alliance is not only stronger than ever, but Putin’s actions brought Finland and Sweden into the fold.

Nor can Xi Jinping take any comfort from Vilnius. Chinese aggression is called out yet again. The principles of mutual collaboration to deter aggression that is at the root of NATO now extends to the Indo-Pacific as Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand give meaning to NATO ‘partner’ nations.

For Canada, NATO remains a cornerstone of our foreign policy. It represents the muscular side of our avowed commitment to the multilateralism that has been the counter-balance since the Second World War to the predominance of our bilateral relationship with the United States. But just as membership brings privileges, it also comes with a membership fee that consecutive governments have shirked.

The meeting in Vilnius should remind us that we live in the world as it is not as we would wish it. As the Irish poet John Boyle O’Reilly observed:

The world is large when its weary leagues two loving hearts divide, but the world is small when your enemy is loose on the other side.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a fellow and host of the Global Exchange podcast with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.