The Mood of Canada: People, the Pandemic and Politics

Most competence issues that can put a government in political peril have to do with logistical problems such as snow clearing, public transportation or natural disaster management. For the past year, the competence stakes have been raised by a pandemic that has killed more than 20,000 Canadians, that only mass vaccinations can end and for which the federal government is dependent on Big Pharma, among other players, for that solution. But Canadians have been taking out their fatigue, and frustration, on the prime minister who has become the face of the response.

Shachi Kurl

Remember, at the dawn of the COVID-19 lockdown, when the denizens of Pinterest told us we needed to have a “pandemic project” for the “two weeks” we were going “on break”? I’d like to stick a pin in them instead.

Twelve months into what has been the most significant event since the Second World War to so broadly affect the lives of Canadians, novelty has been replaced with fatigue, anxiety and yes, hope, as we find ourselves not only in the thick of the pandemic but also on its downslope.

To understand where Canadians are in the spring of 2021, we must better understand where we have been. This informs our personal mindsets, how we view pandemic management, and the ways in which these influence the calculus of federal politics.

People

COVID-19’s impact on economic growth, unemployment, deficit spending, and the financial prospects of individual Canadians has been well canvassed and chronicled. Years from now, we will have the available data and intellectual distance to understand what worked and what did not.

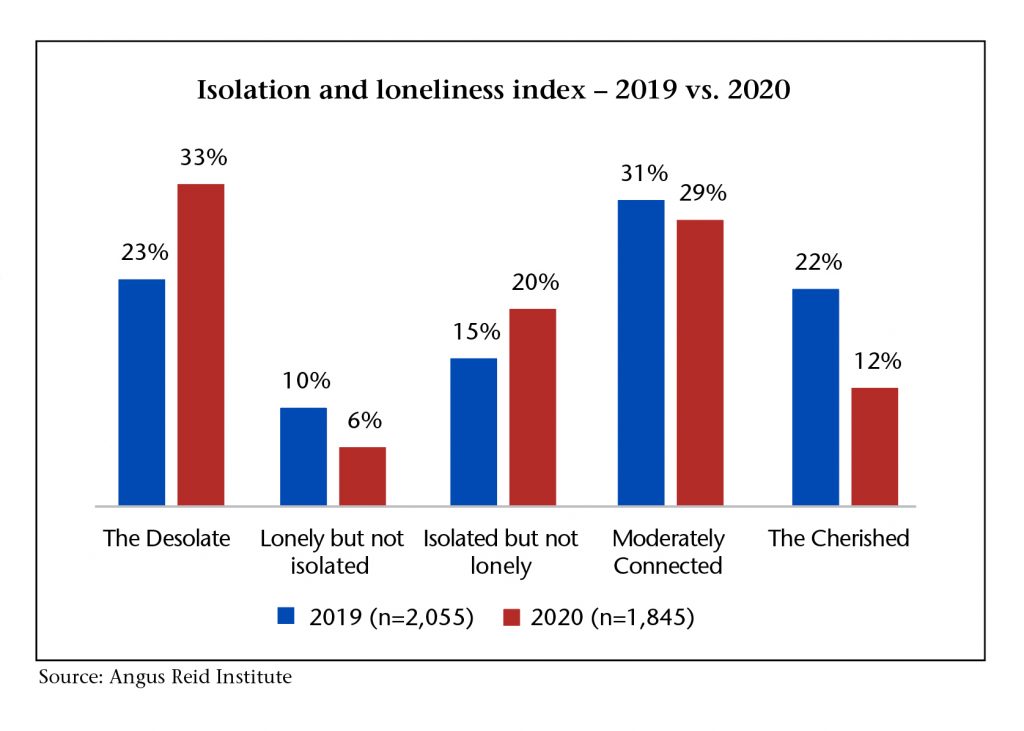

But there are things policymakers can neither fix nor mitigate: the pandemic’s impacts on the psyche, the heart. We have a limited window on what a year of uncertainty and isolation has done to our collective soul. An Angus Reid Institute study last fall compared indexed data regarding self-described levels of loneliness and isolation from 2019 and 2020. The results confirmed what anecdotally seemed obvious. Canadians are less connected, and more bereft than ever.

But there are things policymakers can neither fix nor mitigate: the pandemic’s impacts on the psyche, the heart. We have a limited window on what a year of uncertainty and isolation has done to our collective soul. An Angus Reid Institute study last fall compared indexed data regarding self-described levels of loneliness and isolation from 2019 and 2020. The results confirmed what anecdotally seemed obvious. Canadians are less connected, and more bereft than ever.

Further, people in this country are under little illusion about the road ahead. A new year is traditionally supposed to bring new hope, but at the beginning of February, while Canadians projected the coming 12 months would indeed be better for them than the 12 months past, they nonetheless viewed the next year soberly. Nearly half expect 2021 to be a “tough” year personally, more than twice the number who projected it would be “good” or “great”.

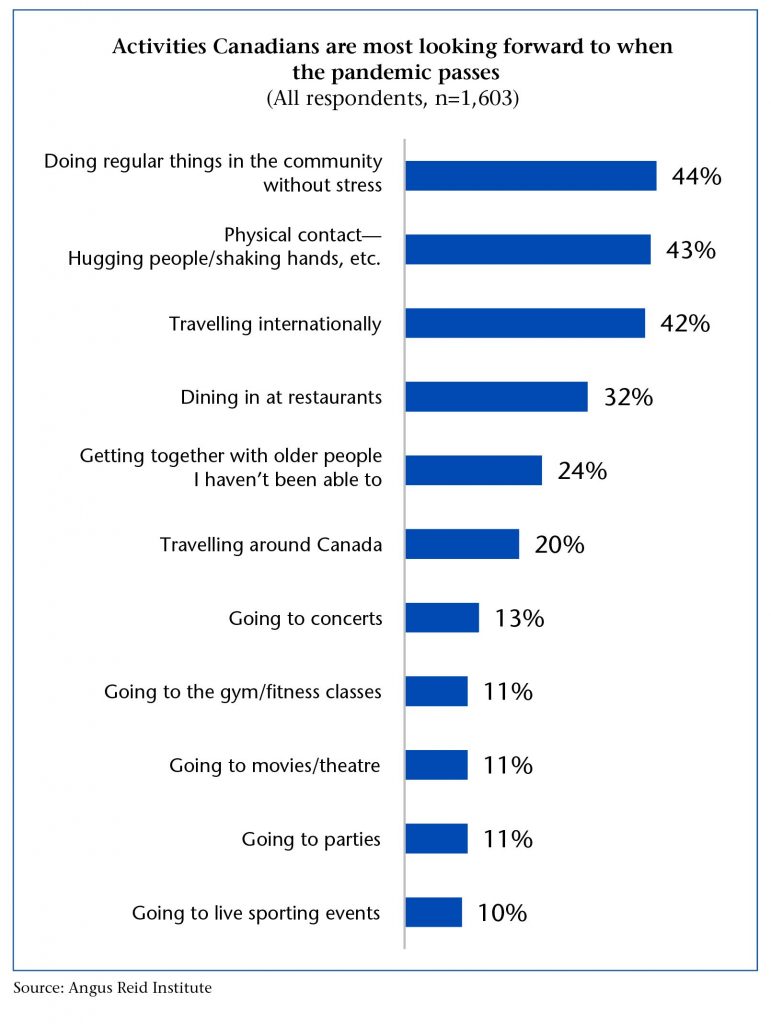

Still, we have dreams of what we’ll do in a post-pandemic reality. At the top of the list? Just living stress-free, hugging loved ones, shaking hands, and the chance to travel abroad again.

Pandemic Management

Of course, planning one’s next vacation or showering grandma with kisses requires an end to the tragic daily toll of new infections, hospitalizations and deaths. And we have very little doubt about what will bring an end to all this: vaccinations. In late January, a majority told the Institute being vaccinated was the only thing that would end the pandemic for then or those in their household. In 2021, “pandemic management” at the federal level means finding vials of the stuff that will save us from getting sick.

Of course, planning one’s next vacation or showering grandma with kisses requires an end to the tragic daily toll of new infections, hospitalizations and deaths. And we have very little doubt about what will bring an end to all this: vaccinations. In late January, a majority told the Institute being vaccinated was the only thing that would end the pandemic for then or those in their household. In 2021, “pandemic management” at the federal level means finding vials of the stuff that will save us from getting sick.

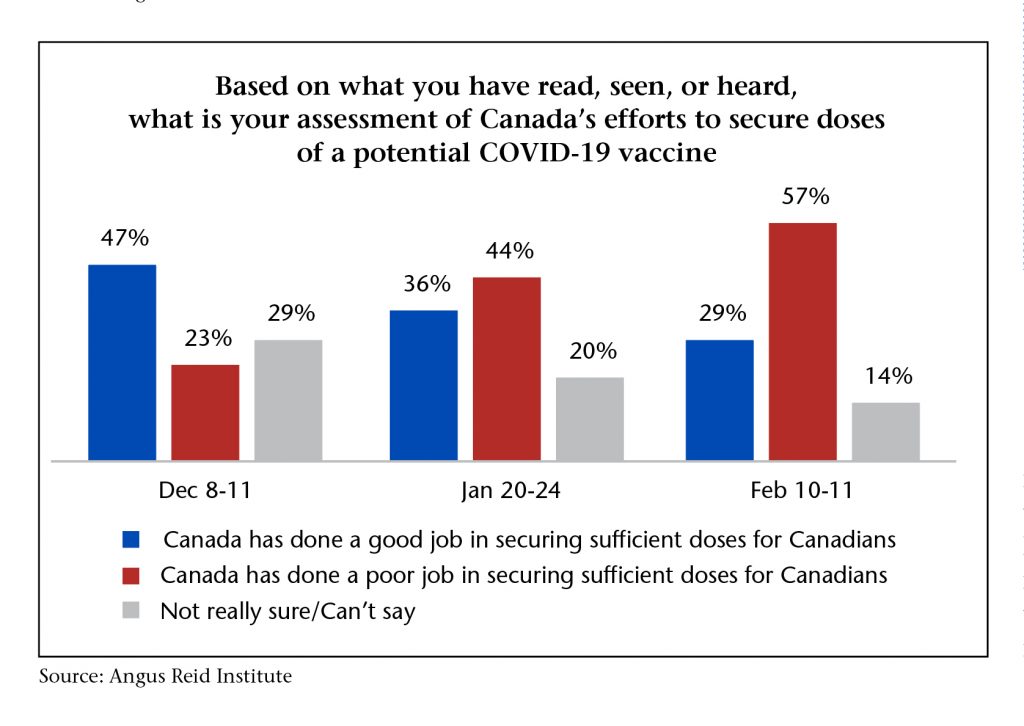

Little wonder then, that the Trudeau government has been under so much pressure to deliver on those precious doses. Let’s be real though: politically speaking, the prime minister may well have done this to himself. A December announcement that this nation would be among the first countries to receive vaccines, combined with previous announcements that we had ordered and secured significant amounts, set up expectations that our federal government was especially on the ball. Little wonder then, that in early December, nearly 60 percent of Canadians were expressing confidence in Ottawa to effectively manage vaccine distribution.

What a difference two months make. No sooner had the Christmas decorations been stored and the post-festive season diets begun than we learned of delays in vaccine shipments, of supply drying up, of uncertainty over timelines, of the delayed realization that quarterly delivery targets meant that while allies such as the US and UK (both capable, unlike Canada, of producing their own vaccines) pressed ahead with mass vaccinations, Canadians were left watching, and waiting.

By mid-February, the number of people who expressed to ARI the same ebullience in the Liberal government’s ability to distribute vaccines had plummeted 30 points. Meanwhile, the number of Canadians who felt their country had done a “bad job” had more than doubled.

By mid-February, the number of people who expressed to ARI the same ebullience in the Liberal government’s ability to distribute vaccines had plummeted 30 points. Meanwhile, the number of Canadians who felt their country had done a “bad job” had more than doubled.

And, as the mood of the nation soured on the not-great news, so too did the perception of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. The PM who pulled his way back into the good books of at least half of Canadians post-WE Charity scandal has since seen his personal approval sink five points to 45 per cent on dim views of a deficient delivery. Indeed, the same mid-February survey found that most describe Canada’s vaccination efforts relative to other nations thus far as a “failure”.

Politics

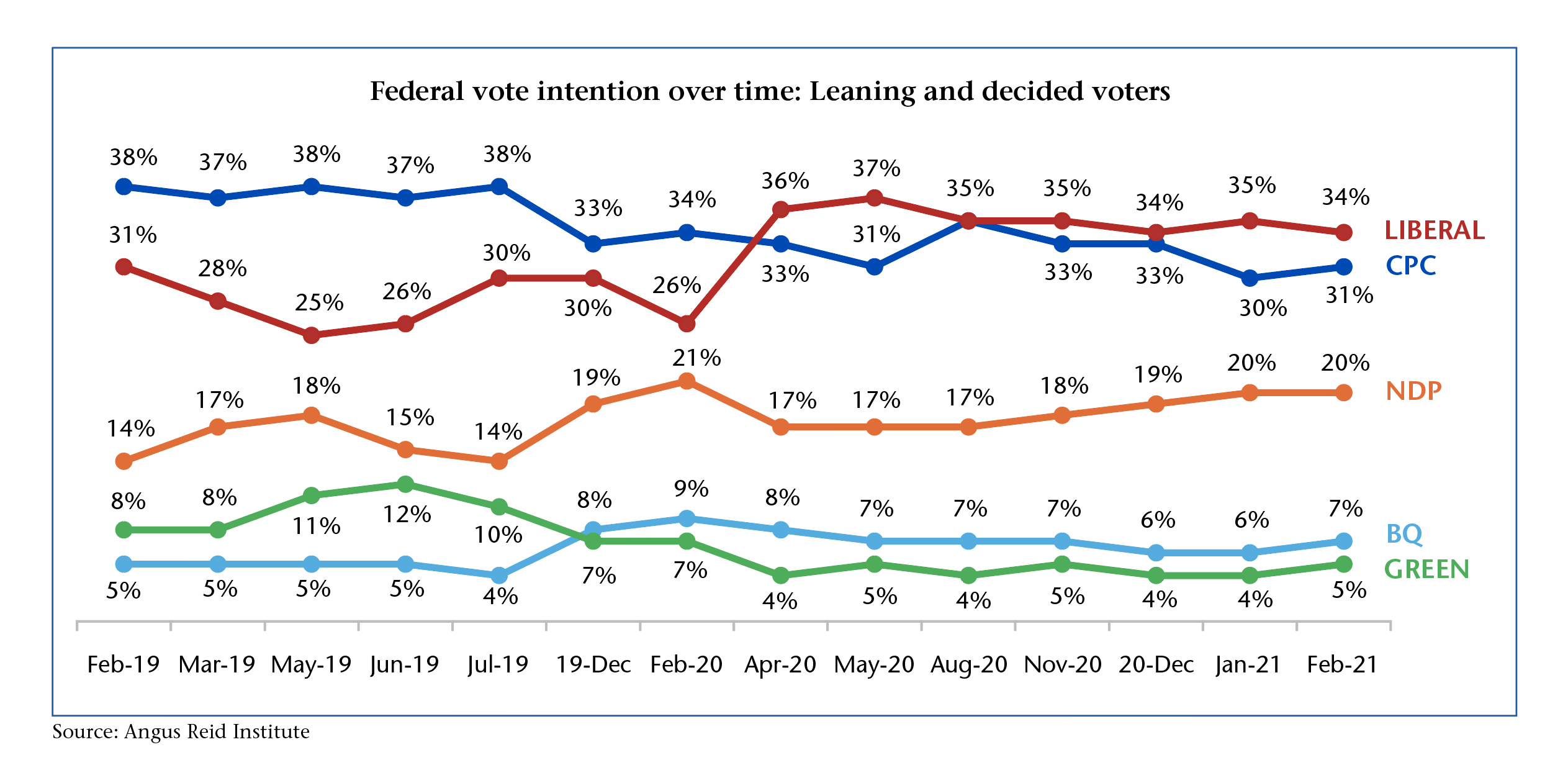

So, one might think if the country is ticked off at the PM, his party’s electoral fortunes (with apologies to Bruce Springsteen) would be similarly riding a down bound train. But … not really. In fact, the Liberals retain a lead in vote intent (albeit a tiny one).

What gives? Well, if Canadians are feeling frostier towards Trudeau, they’re not exactly warming up to Opposition Leader Erin O’Toole. The Conservative Party chief has held the position for less than a year but has yet to endear himself to many Canadians. His favourability rating continues to fall while his unfavourability continues to rise. Toward the end of February, half of Canadians told ARI they viewed him in a negative light.

What gives? Well, if Canadians are feeling frostier towards Trudeau, they’re not exactly warming up to Opposition Leader Erin O’Toole. The Conservative Party chief has held the position for less than a year but has yet to endear himself to many Canadians. His favourability rating continues to fall while his unfavourability continues to rise. Toward the end of February, half of Canadians told ARI they viewed him in a negative light.

Over more than a five-year tenure, Trudeau has proven time and time again his dual talents for getting into spectacular trouble, and then getting out of it. Canadians are a “seeing is believing” bunch. Watching our elderly compatriots bravely get their jabs significantly changed the level of enthusiasm and urgency we collectively felt about being vaccinated.

Will the spring—and an anticipated surge in vaccine supply—not only hearken a thaw in temperatures but also a thaw in the Canadian electorate’s sentiment towards Trudeau? Only Pfizer, Moderna and maybe AstraZeneca know.

Contributing Writer Shachi Kurl is President of the Angus Reid Institute, one of Canada’s leading national public opinion and research firms, based in Vancouver.