The Mood of Canada: Beyond the Coronavirus Summer of our Discontent

Shachi Kurl

Six months in, no clear end in sight. As Canadians turn their first major corner living with COVID-19, here’s some developments to watch for this fall, and some thoughts on how public opinion will affect them.

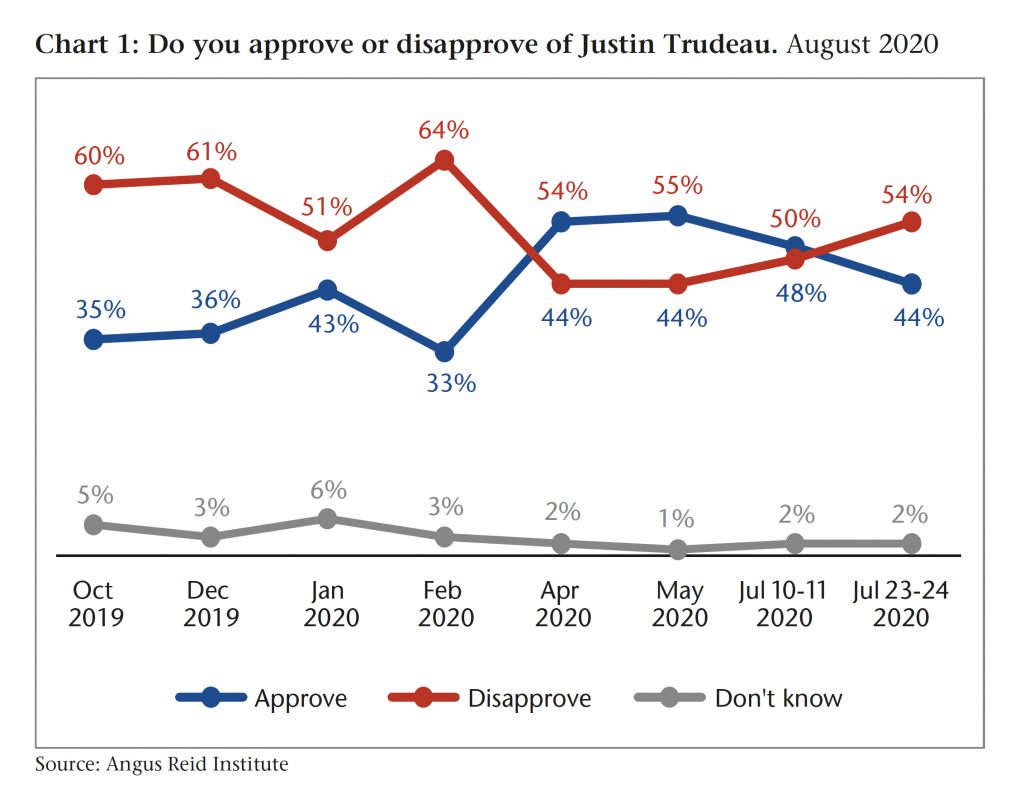

At the Angus Reid Institute we were in the field in mid-August, asking Canadians whether they approved or disapproved of Justin Trudeau as prime minister. His approval rating, high during the first several months of the pandemic, definitely took a major hit with the WE Charity negative news explosion over the summer.

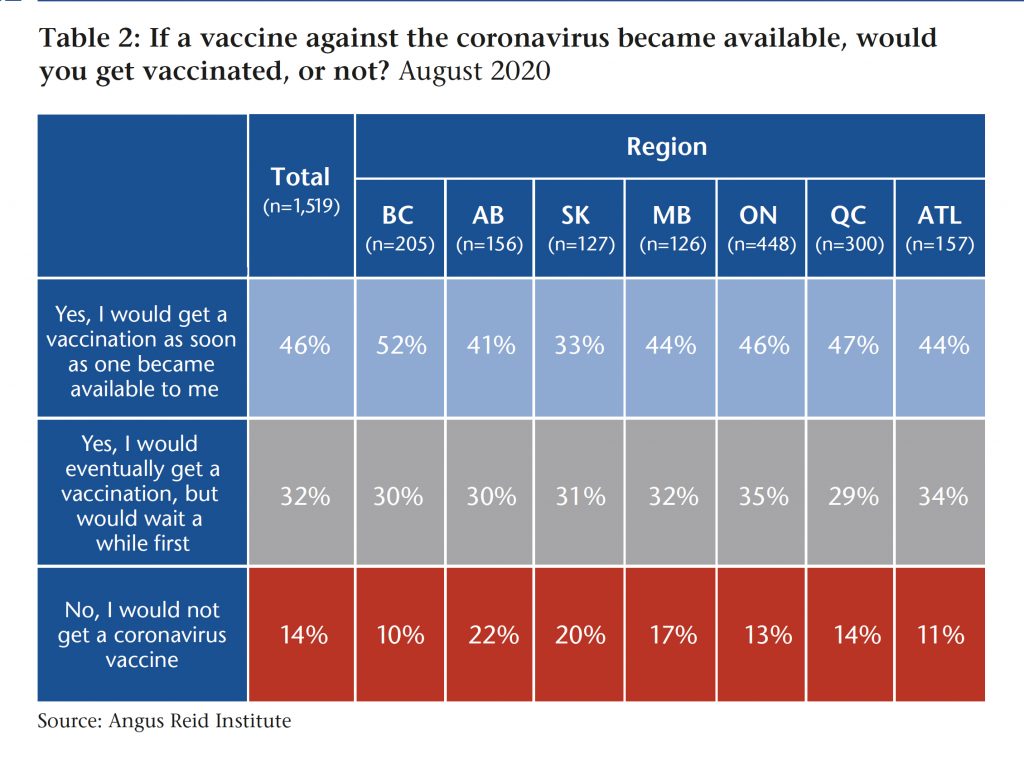

We looked at a lot of things Canadians are concerned about, and the re-opening of schools was high on the anxiety list, although Canadians as a whole were more anxious about the situation than they were relieved to have come through it. And while generally approving of vaccinations (46 percent) should an effective one become available, many said they would wait a while before getting one (32 percent). In terms of diversions, the prospect of the summer NHL playoffs beginning in August had 72 percent of Canadians very or somewhat excited about the prospect of the return of hockey.

It would have been too much, I suppose, to have hoped in this most trying of years the political Gods might have given us the summer off. If ever we needed to flake out, to swing in our hammocks, to lounge lakeside and contemplate our altered lives in the “new normal”, surely it would have been these past weeks.

Alas, this summer of our coronavirus discontent was also punctuated by non-stop political drama that started with a now-cancelled contract to WE Charity to run a student volunteer program and ended with the awkward resignation of Finance Minister Bill Morneau. Officially, to try for the job of Secretary General of the OECD. All but officially, to quell what was turning into open warfare between the Prime Minister’s Office and Morneau, whose proximity to and expensive travel with WE did an already- damaged Justin Trudeau no favours in the affair.

In an administration pocked by re-sets, Morneau’s departure offers a tantalizing opportunity for another, albeit risky one. For better or for worse, Trudeau has been the face of his government. Having soared in approval in the first months of the pandemic, the scandal has largely eroded whatever gains he made.

In a largely anonymous cabinet, Morneau was one of the better known, but least publicly liked ministers. He is now replaced by one of his only other well-known cabinet colleagues Chrystia Freeland.

Freeland has a high profile and has carried high approval ratings. But she will come to one of the most demanding and high-stakes jobs in government already carrying her duties as Deputy Prime Minister. Tasks such as transitioning from CERB to an enhanced Employment Insurance program, getting women disproportionately affected by the pandemic back into the workforce, and re-starting Canada’s economy from all but a standstill are each daunting enough. Freeland may be a political dynamo, but a super-powered eight-armed Vedic goddess she is not. Stretching any mortal this thin also highlights what has been a chronic deficit in the Liberal caucus’ bench-strength. It’s muscle they’ll need build in order to fend off attacks from a Conservative Party refreshed with new leadership.

Little wonder then, that Trudeau prorogued Parliament, announcing August 18 the beginning of a new session on September 23, only two days after the previous session was to have resumed. But he also promised an early vote of confidence on the new Speech from the Throne. The opposition Conservatives may not like it, but hey, Stephen Harper set the precedent in 2008 proroguing a minority House to avoid defeat on a confidence motion.

Little wonder then, that Trudeau prorogued Parliament, announcing August 18 the beginning of a new session on September 23, only two days after the previous session was to have resumed. But he also promised an early vote of confidence on the new Speech from the Throne. The opposition Conservatives may not like it, but hey, Stephen Harper set the precedent in 2008 proroguing a minority House to avoid defeat on a confidence motion.

Luckily for the Trudeau government, what is likely to be the single biggest stressor for parents over the next three months falls under provincial jurisdiction. As tantalizing as the prospect of no longer home-schooling the kiddies may be, what appears to be patchwork of at times nebulous, yet-to-be-defined, back to school plans from province to province offers little comfort. Guidance around social bubbles is effectively popped with all the small folk hanging around with each other again. Multi-generational households that depend on grandparents for pick-ups and drop-offs are flummoxed.

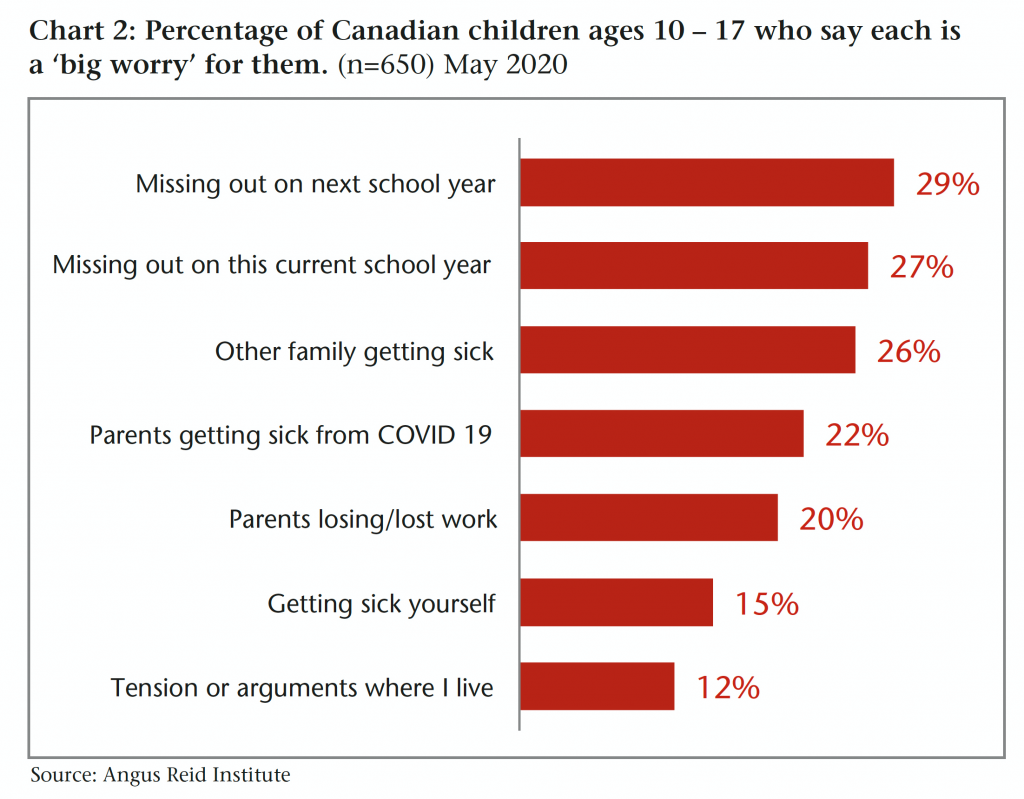

Two key upsides of sending kids back to school: it enables many parents without alternative childcare to go back to work. It’s also what the kids want. In the spring, just six weeks into the transition to learning from home, Canadian children were so over it. They were missing friends, feeling unmotivated, and worried about falling behind in class:

Sending kids back to class will represent an unprecedented public health experiment. If it doesn’t go well, expect the grown ups to give their provincial politicians failing grades.

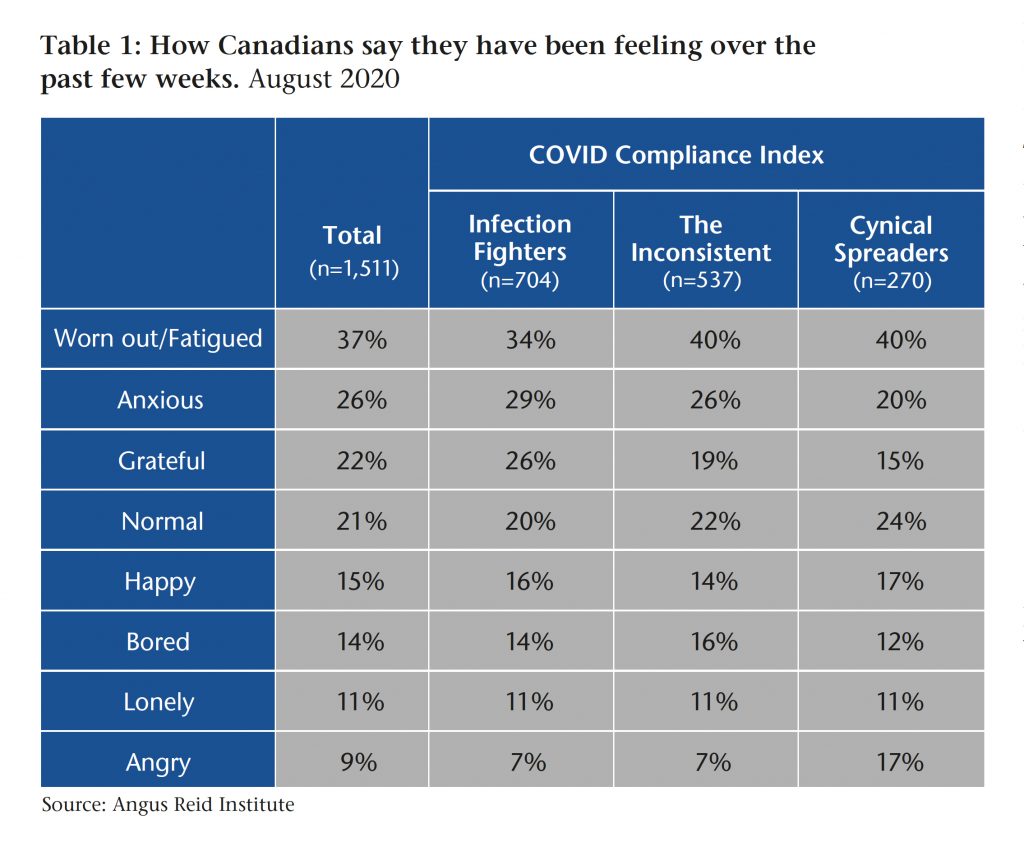

Coronavirus fatigue set in a long time ago, but it’s how we’re dealing with it that sets segments of Canadian society apart. A late summer study revealed that while almost half of Canadians continue to fight their best fight against community transmission by practicing fastidious hygiene, wearing masks and keeping their social bubbles small, about one-in-five sit on the other end of the spectrum, and could care less about precautions. These “Cynical Spreaders” are not only more likely to socialize with larger groups of people, (often not well known to them, often inside, without masks), they also take a more jaded view towards the public health officials and politicians exhorting them to change their ways.

A number of factors delineate the “Infection fighters” from the “Cynical Spreaders”—but one of the most striking differences is age. The majority of those 65+ are in the uber-cautious group. Those aged 18-24 are twice as likely as the national average to be found among the don’t care bears. In terms of their mental and emotional health, the Cynical Spreaders are far more likely to define “anger” as the emotion they’ve experienced the most lately when compared to other segments. By contrast, Infection Fighters are significantly more likely to say they’ve been feeling “grateful”.

A number of factors delineate the “Infection fighters” from the “Cynical Spreaders”—but one of the most striking differences is age. The majority of those 65+ are in the uber-cautious group. Those aged 18-24 are twice as likely as the national average to be found among the don’t care bears. In terms of their mental and emotional health, the Cynical Spreaders are far more likely to define “anger” as the emotion they’ve experienced the most lately when compared to other segments. By contrast, Infection Fighters are significantly more likely to say they’ve been feeling “grateful”.

If there is such a thing as “back to normal”—we will not even be able to dream of it until much awaited vaccines find their way up our noses or jabbed into our arms. It could be a long wait. Whenever this potentially life saving substance is made available to the general population, fewer than half of Canadians say they’ll be lined up immediately to be vaccinated. Indeed, more than 20 per cent say they either won’t get the vaccine or aren’t sure. Willingness to be vaccinated varies regionally, which means public health officials in some provinces will have more work to do than others if they hope to achieve vaccination levels above 70 per cent—the number some say is needed to achieve herd immunity.

What’s driving some of the reticence—or at least the desire to “wait and see”? Consider that a majority, six-in-ten—express worries about side effects from a hypothetical coronavirus vaccine. One-fifth fret the vaccine won’t be effective anyway. And so it goes. Shades of anti-vaccination sentiment towards other illnesses are revealed around a vaccine that doesn’t yet exist. New sickness, old arguments. In one head-shaking finding, 25 percent of those who say they wouldn’t get a vaccine themselves say vaccination should be mandatory… for health care workers.

When the poet Juvenal wrote of “bread and games”—it was to illustrate the shallowness of a society neglecting greater concerns. Let there be no mistake. Canadians have been intensely focused on the greatest concern of their lifetime for the last six months. A little diversion is healthy.

When the poet Juvenal wrote of “bread and games”—it was to illustrate the shallowness of a society neglecting greater concerns. Let there be no mistake. Canadians have been intensely focused on the greatest concern of their lifetime for the last six months. A little diversion is healthy.

Little wonder then, that hockey fans left indefinitely in the penalty box when the NHL suspended its season took to the midsummer playoffs like a power forward to Gatorade. The games have been a little odd, what with no fans and all, but hockey is hockey, and we have been happy to have it.

Sadly for some, the CFL is done for the season, having failed in their bid for $30 million from the Trudeau government. For a government that calculates (and sometime spectacularly miscalculates) funding decisions based on political math, bailing out the Canadian Football League may have earned thanks in the end zone, but not at the ballot box. CFL fans are a passionate bunch. But predominantly over the age of 55, the majority male, they correlate more closely with voting Conservative than Liberal NDP or Green.

Contributing Writer Shachi Kurl is Executive Director of the Angus Reid Institute, the national non-profit public opinion research and polling firm based in Vancouver.