The Middleman: How Mackenzie King Helped Churchill and Roosevelt Save the World

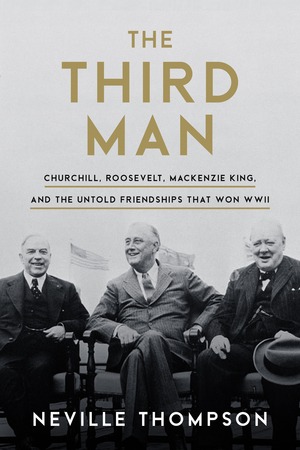

The Third Man: Churchill, Roosevelt,Mackenzie King and the Untold Friendships that Won WWII

Neville Thompson

Sutherland House Books, 2020

Review by Don Newman

He was the one at the edge of the iconic photograph; the one looking extremely pleased to be included. The third wheel on the two-wheeled Allied bicycle that ultimately crushed Adolf Hitler and his murderous Nazi war machine.

At least that is the way most Canadians saw him at the time. And it is the way he is remembered now when he is thought of at all. But William Lyon Mackenzie King, Canada’s 10th prime minister, was a lot more than that. As carefully documented in historian Neville Thompson’s aptly titled and compelling book, The Third Man, King played a bigger and often key role in developing and supporting the friendship and cooperation of Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt that underpinned the Atlantic alliance.

The role that King was able to play in acting as mediator, middleman and occasional conduit and interpreter for messages between Roosevelt and Churchill was greatly helped by the fact that he knew both men before the war started. His and Churchill’s paths crossed in Ottawa in 1900. King was then an up-and-coming public servant in the federal government. Churchill was early on in his career of being CHURCHILL, a one-named, all-caps worldwide celebrity that started in 1899 after he escaped from a Boer prison camp while covering the South African War and then immortalized it as an adventure in newspaper articles, books and speeches.

In fact, Churchill was in Ottawa as part of a North American tour speaking about his exploits. The meeting was at Government House – now Rideau Hall — which visiting British aristocrats treated like an early Air B&B as the Governor General was, in those days, a fellow British aristocrat. That meeting didn’t register much with King and not at all on Churchill. But a second encounter in London in 1906 set them off on a friendship and collaboration that lasted through each being in and out of office – and back in again – that lasted through the Depression and the Second World War until King’s death in 1950.

King probably crossed paths with Franklin Roosevelt at Harvard University in 1921 when, during his first term as prime minister, he received an honourary degree while Roosevelt was on the Harvard Board of Overseers. Neither man seemed to have any recollection of a meeting. But by October of 1935, Roosevelt was in his first term as president of the United States. He invited King, who had only recently returned to office, to visit him and stay in the White House. The ostensible reason was to sign a limited free trade agreement, which they did. But the real reason was to start a collaborating friendship that was every bit as close as the one King had developed with Churchill. It was during that visit that Roosevelt asked King to help facilitate good relations with Britain. The Canadian prime minister readily agreed.

Relying to a great extent on the diaries in which King meticulously recorded the events, conversations and impressions of the people he had met, along with his triumphs and disappointments, Thompson reveals that King at times before the war had critical views of both Churchill and Roosevelt. Before their meeting in 1935, he had regarded Roosevelt’s New Deal economic program as too radical and interfering in the market economy. Another time he wrote that the President’s “demagoguery” was as bad as Hitler’s.

King was sometimes able to mediate differences between the British prime minister and the American president. He also used his place of influence to get Canada as much recognition as the others were willing to give.

Throughout most of the 1930s, Churchill was out of office in Britain; a Conservative parliamentarian at odds with his government’s appeasement of Germany and calling for Britain to re-arm. That was not the way King saw it. As prime minister of Canada in 1938, he sent a congratulatory message to British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain after the latter signed an agreement with Hitler giving Germany about half of Czechoslovakia in return for the spectacularly naive quid pro quo of “Peace in our Time.” Just less than a year later, the war started after Germany invaded Poland and Chamberlain’s agreement came to symbolize for posterity the futility of appeasement. Still, King held on to his original views, telling his diary that Churchill’s call for re-armament made him “one of the most dangerous men I have ever known.”

But those disagreements vanished, particularly as the war progressed. King was sometimes able to mediate differences between the British prime minister and the American president. He also used his place of influence to get Canada as much recognition as the others were willing to give for our country’s contributions.

At the time, King’s most widely recognized role as a partner in the Atlantic alliance was at the two Quebec Conferences during the war at the Citadel in Quebec City — the first in August of 1943, the second in June of 1944. At each, King’s participation had to be carefully negotiated. The Canadian Prime Minister was a trusted confidant of both men, but it was Churchill and Roosevelt who were running the war. King understood that and was not present in the closed negotiating sessions. But since he had meals with the other two leaders and understood all the issues, he played a de facto role in both sets of talks, although not a pivotal one.

Still, the conferences were in Canada, on his political turf, which both burnished King’s brand as a statesman and provided some recognition to the thousands of Canadians serving, and lost in, the war effort. During an existential battle for freedom, King was in all the photographs of both Quebec conferences, alongside the two leaders history would name as its heroes. A third man perhaps, but a very visible third man.

Policy contributing writer and columnist Don Newman is a lifetime member of the Parliamentary Press Gallery and author of the bestselling Welcome to the Broadcast.