The Many Stages of Chrystia Freeland

Policy foreign affairs writer and veteran diplomat Jeremy Kinsman first met Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland over dinner at a mutual friend’s apartment in Moscow in the tumultuous early 90s, when he was Canada’s ambassador to Russia and she was a young journalist. Since that moment, he has seen her dance on a tabletop at the Hungry Duck pub, provoke Vladimir Putin, finesse Donald Trump and become the most powerful woman in Canada. It’s been a trip.

Jeremy Kinsman

January 2020

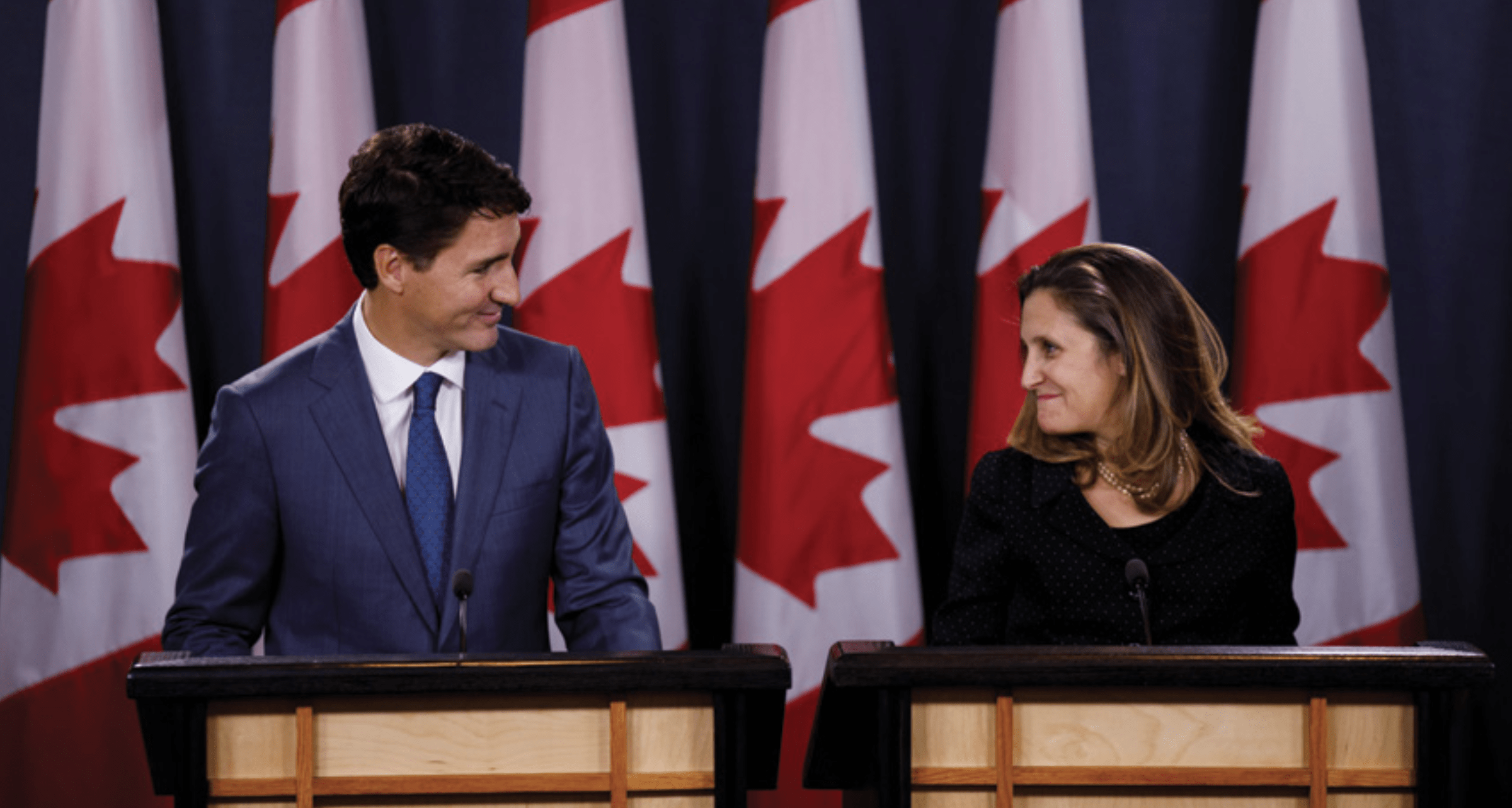

Seeing Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland on December 10, holding up the just-signed NAFTA II agreement in Mexico City on live television alongside President Manuel López Obrador, towered over by U.S. and Mexican negotiators, was a reminder of how very far she has come.

Freeland was named foreign affairs minister in January, 2017 to defend Canada’s vital interests against a hostile overturning of the very notion of North American cooperation by Donald Trump.

It was doubtful that anybody else in government had the chops, the knowledge, the chutzpah, and perhaps decisively, the status beyond Canada to effectively counter the bullying, grandstanding, and outright misrepresentation that can characterize White House negotiation in the age of Trump. With a superb professional team, Freeland pulled it off.

As evidence mounted over the course of the last year that the prime minister’s judgment could use buttressing from people with significant experience, he called on Chrystia Freeland to step up as a clear number two in the country. He needs her help.

Given that the dangling question—how much farther can she go?—has only one answer, the situation is a bit delicate for both Freeland and Trudeau. In the meantime, it’s worthwhile to look back at who she is, where she’s from, and what she’s done.

I have known Chrystia Freeland since she turned up in Russia 25 years ago as a newbie reporter, stringing out of Kyiv in newly independent Ukraine for several A-level UK publications. We first met her for dinner in Moscow at John and Elizabeth Gray’s, back when the Globe and Mail and every other Canadian outlet of consequence maintained a Moscow bureau to cover the monumental story of the end of communism, the Cold War, the Soviet Union, and in effect, the 20th century. Canadians, especially—possibly because of the culturally and politically potent Ukrainian-Canadian community—had also to cover the new story of how an independent Ukraine was working out. This bright, Ukrainian-and Russian-speaking, high-energy, dauntless young woman fresh out of Oxford, a Rhodes Scholar from Alberta, was a real find.

She had come to Kyiv to join her mother, Halyna, who was helping the Ukrainians draft their inaugural constitution. Both Chrystia’s parents were legal professionals. Halyna was a scholar, who had met Donald Freeland at law school in Edmonton. He is also the son of a lawyer, whose family roots were on a farm in Alberta’s Peace River district, though Donald earned his living mostly practising law in the provincial capital. Donald’s dad had returned to Peace River from overseas war duty with a war bride from Glasgow. Grandmother Helen dressed Chrystia and her sister in kilts as little girls; Scottish blood mingles with Slavic in those ministerial veins.

But back in Moscow at the Grays, the dinner table talk wasn’t about Scotland: it was all Ukraine. Chrystia was trying out the idea, then simmering in Kyiv, that maybe Ukraine ought to hold on to its Soviet-legacy nuclear weapons to bargain for air-tight security guarantees from Russia, which clearly had trouble coming to terms with the idea of Ukraine as a separate state, no matter what deal Boris Yeltsin had struck with Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk to bust up the USSR and thereby enable Yeltsin to replace Mikhail Gorbachev. For a Canadian ambassador then in the thick of a massive and costly NATO campaign to help Ukraine and Kazakhstan rid themselves of their worrisome “loose nukes”, this was a destabilizing and unwelcome thought.

We settled warily but amicably, and parted as new friends. Ukraine did become officially a non-nuclear weapons state, and Chrystia soon after joined the swelling crowd of Westerners in Moscow, hired as a reporter by the Financial Times. John Lloyd, who was the FT’s Moscow bureau chief recalls “It was very clear she was bright, driven to get the story right, always after the minister/official/dissident who could tell the story best. She was, of course a Ukrainian patriot: but she was clear about keeping her views out of the reportage.”

And she did, doing excellent reporting from Russia, initially on the economic chaos that nobody understood, detailing how Western treasury departments and multilateral institutions (notably the International Monetary Fund) were whipping shock therapy on Russia—at the grotesque cost, as The New Yorker’s David Remnick put it, of “the destruction of everyday life.”

There was an exuberance to Chrystia. Montreal take-no-prisoners freelancer Sandy Wolofsky recalls our post-Chrétien visit “wheels-up” party in the unforgettable, Canadian-operated Hungry Duck pub, when Freeland was late-night dancing on a tabletop. Still, to quote Lloyd again, she came across as a young “woman of huge intelligence, energy, and good sense.” When John left Moscow at last, Chrystia, still in her twenties, was named bureau chief for the FT.

She had been super-bright as a kid, winning a scholarship out of high school in Edmonton to a world college stint in Italy followed by a scholarship to Harvard where she studied Russian history. But she didn’t surf her way through exams—she did all the work, all the way.

And so she did at the FT, in London, before being hired away to be deputy editor of the Globe and Mail in 1999, then heading back to the FT in London as its Deputy Editor. When a male colleague 20 years older got the top job, Chrystia went to New York as the FT’s U.S./Americas editor and columnist on international finance and business. In 2010, looking for new challenges, she got hired away as Reuters global editor at large, based in New York, and then spearheaded their leap into the new media world as editor of Thomson Reuters Digital. Her rise in journalism had been phenomenal. As a journalist, Chrystia produced top-flight deadline copy that was out there for all to see. As an editor of top-flight operations, she got the best out of talented people and, said Lloyd, was “loyal up and down.”

Along the way, she had married a soft-spoken, fine British writer, Graham Bowley (now with the New York Times, commuting to NYC from Toronto). Together, they have raised three non-passive children. But it would have been impossible without help, especially from her mother, Halyna, who, having done her best on Ukrainian constitution-drafting, moved into the New York household for her grandkids. When she tragically died a decade ago, it was “the Ukrainian ladies” of Nannies International who helped keep it all afloat.

Chrystia somehow found time to write two big books. Sale of the Century (2000), about Russia’s rigged privatizations, remains a must-read for those of us who still care about what the hell went wrong with the naive best intentions for Russia’s forward journey from Gorbachev’s heroic acts that changed the world. Plutocrats (2012) is a sweeping survey of the landscape of international capitalism, in the wake of its breakdown, which exposed 2008’s financial frauds, and led to the near-collapse of the global system. It is clear from her scathing narrative that Freeland is no neo-liberal.

So, she was super-busy. It wasn’t her ambition to get into politics, but as she did tell me over some Chardonnay on a shared flight to Newark a decade ago, she wanted to come back to Canada. But Canadian media space doesn’t offer many opportunities to operate at the very top. When the Liberals came calling, having done a big and ambitious book, and with enough-already of New York City, she wondered if public service could be a rewarding Canadian alternative.

Chrystia agonized about running for office. The Liberals were in third place, going nowhere fast. But party politics is actually pretty close to the family bone. Halyna had run in Edmonton Strathcona in 1988—for the NDP! And father Donald Freeland’s paternal aunt Beulah was married to long-time Peace River MP Ged Baldwin, who was Progressive Conservative Opposition House Leader for years.

She went for the Liberal nomination to replace Bob Rae in a by-election in Toronto Centre in 2013 and was elected to Parliament. It was around then that Ukraine began to boil. The Conservative Party had been trying under Jason Kenney’s organization to break into the Liberals’ traditional appeal to immigrant communities. The Canadian-Ukrainian community, more than a million strong, was a prime target.

Ukrainian Canadians, refugees from the Soviet Union’s revolution and oppression, especially from the tragic Holodomor, the forced famine of the early 1930s that killed an estimated 3.5 million Ukrainians (and many Russians), are mostly sourced to Galicia, Western Ukraine. It was historically part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was more permissive of Ukrainian cultural autonomy and language rights than the Soviet Union, which repressed them. So, there is ample historic anti-Moscow nationalist sentiment in Lviv, which was the capital of Galicia, that still animates Canada’s Ukrainian community.

When the Euromaidan protests broke out in 2014 between the wary union of reformist and nationalist Ukrainians and the Moscow-supported regime of Viktor Yanukovich, Stephen Harper, Kenney and the Conservatives chose the side of Ukrainian diaspora votes. Harper wouldn’t shake Vladimir Putin’s hand at a G20 meeting without (so he boasted to Canadian media) snarling, “Get out of Ukraine.”

But the diminished Liberals had one Ukrainian/Canadian parliamentary card to play. They sent Chrystia off to Kyiv, where she encouraged the young reformers occupying the Maidan. Speaking the language, being a master communicator, owning an apartment with her sister, Natalka, overlooking the Maidan, she was a hit, carrying weight precisely because she was an old Moscow hand. The Russians noticed.

After the Liberals won in October, 2015, Chrystia was a shoo-in for a top economic portfolio. She must have been hoping for Finance. Over-reaching? Hardly—read her book. But Bay Street doesn’t read books, so she became minister of trade.

There haven’t been that many political leaders in Canada who actually had a record of running operations of consequence—Brian Mulroney and Paul Martin stand out. Chrystia stood out in that first Trudeau cabinet for competence and experience, including a sound instinct for knowing whom to connect with and what made them tick.

Her biggest task was to deliver the CETA trade deal with the European Union. As a 21st-century economic partnership treaty that breaks new progressive ground, CETA makes the new NAFTA look almost clunky. It’s said that it took seven years to negotiate. Actually, it began in 1972, but that’s another story. Jean Chrétien reanimated it, Premier Jean Charest forced the issue with France, and ultimately it fell to the Harper government to open formal negotiations. But it would take Chrystia’s leadership to pull off a complex and ground-breaking comprehensive deal through very hard work, superb personal connections with top Europeans, and political persuasion of parliamentary doubters in several capitals.

Cut to November 2016, and the world gets Donald Trump and his vow to tear up NAFTA. It was hard to imagine the all-important NAFTA re-negotiation with the America Firsters under anyone else, and so she replaced Stéphane Dion as foreign minister.

At the top, it was Chrystia Freeland head-to-head against U.S. Trade Representative Bob Lighthizer. They seriously underestimated her (always a plus for a negotiator) and weren’t very nice, resenting her exceptional media impact, especially in Washington. Who the hell did she think she was? Only Canada’s foreign minister. And she was about as good as any, ever. As John Delacourt writes elsewhere in this issue of Policy, she never negotiated in public but somehow came out with all the good lines, that, bit by bit moved the political dial in our direction.

She was tough and she and her team were tough-minded enough to know Canada could live without a deal if we had to. It showed. In the end, it was Trump who ended up most needing the win. It was Chrystia who could say at the end win-win-win, and who made Bob Lighthizer dinner in her Toronto kitchen with the kids.

The U.S. deal was the essential national existential defensive save. It was historic. But as foreign affairs minister, she began some other things that are also very important. I thought they would rank her tenure with Joe Clark’s and Lloyd Axworthy’s as among the very best if she stayed to press these themes across the global board. They have laid the groundwork for her successor, François-Philippe Champagne, to pursue, especially mounting a like-minded rally in support of inclusive democracy and liberal internationalism. In the pro-Russian, anti-Western, pro-nationalism media out there she is caricatured as an adversary, a human rights interventionist.

In reality, her much-publicized stand in favour of Saudi women was not from some longstanding human rights vocation. She had been primarily an international business writer. But in the summer of 2018, the facts were eloquent and dark. University of British Columbia mentors reported that Loujain al-Hathloul, who had done a degree there while becoming committed to gender equity was being tortured back home for advocating women’s rights. She wasn’t a Canadian citizen but the news distressed Chrystia, and when Samar Badawi, the sister of jailed and flogged blogger Raif Badawi, got arrested a few weeks later, the minister took a critical stand against Saudi behaviour on behalf of Raif Badawi’s wife, Ensaf Haidar, who had fled to Canada for asylum.

Freeland believed the sincerity of our values was on the line. She wasn’t content just to signal our virtue. She believed we had to help.

A tweet from our Embassy in Ryadh that they should at once release Samar Badawi provoked the Saudi theocracy to a massive over-reaction. Chrystia was then slammed by some pro-business groups for letting do-gooder naïveté put Canadian jobs at risk. She didn’t get much international support at first—until Jamal Khashoggi was butchered.

The experience was jarring. It made Chrystia Freeland want to use her ministry for value issues as well as macro-trade deals.

Trump’s reversal of U.S. policy on human rights and international cooperation, notably climate change, as well as what he was doing to democracy’s reputation were preoccupying other like-minded democratic leaders. Chrystia found herself building a caucus, an informal alliance with her colleagues in Berlin, Paris, Stockholm and elsewhere. Last year, German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas invited her to address Germany’s heads of mission from around the world. Germany awarded her the prestigious Warburg Award—for the first time to a Canadian—for steering Canada’s firm commitment to multilateralism and to shared transatlantic values. He praised Chrystia for standing by her convictions. “You are an activist in the best sense of the word—both principled and realistic.”

She has tried to apply the rights and democracy value proposition to other relevant international conflict issues where Canada had some standing. But a few outreach efforts fell flat or didn’t happen. For example, as minister, she didn’t go to Africa. She would have, but had to triage her time. Overall, our relationship with Russia could scarcely be worse. It’s partly their fault, obviously. Chrystia Freeland actually did want to connect even though she was on their sanctions list. But when she did meet Putin and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov at a G20 event, Putin’s well-known inner misogynist seems to have reacted badly to this rather small, very bright Russian-speaking minister setting out some ideas that weren’t wholly congenial to Putin’s souring world view. The relationship flat-lined near zero.

On China, the ruination of relations is not her fault. She wasn’t part of the Meng Wanzhou ambush but has loyally defended what happened as respecting the rule of law. The cruel reprisal captivity of the two Michaels sears at her, as it should. China insiders confide that her Beijing counterparts respect her. Still, however the immediate hostage situation plays out, things with China have changed. We’ll not be as friendly with Beijing as we once thought we would be, but nor can we be hostage to an emerging epochal duel for global leadership between the world’s two biggest economies.

As last year produced government blunders and polls indicating minority government prospects, her own performance in the government stood out. As veteran Liberal strategist Peter Donolo puts it, “Her well-tuned sense of political theatre was a contrast to the slavish attachment to talking points exhibited by most of her cabinet colleagues,” who seemingly hadn’t been given her latitude. Once the election results were in, it became inevitable that she would be transferred out of foreign affairs because of the Alberta credibility deficit and the evident need of Trudeau to have a strong deputy.

It now makes her a potentially decisive figure across the Canadian landscape. Let’s be candid. Her good judgment is going to be calling some big shots in this minority government, in place of big shots in the PMO calling them in the last one. When the ministerial mandate letters surfaced on December 13, Freeland’s described an unprecedented level of deputized executive power. Justin Trudeau ought to be the beneficiary, and good for him for understanding her value.

Howard Balloch who was a long-time ambassador to China, comments:

“Chrystia Freeland listens, deeply and intently, to as wide a spectrum of informed views as possible as she formulates her own.” In this, she reminds Balloch of previous very successful foreign minister Joe Clark whose “same respect for both facts and the complex prisms that refract perception of those facts when seen from other cultures and backgrounds,” also put him in charge of federal-provincial relationships at a vexed time in our history.

Let’s hope it works out for Freeland, for Trudeau, and for the country; that the Peace River part of the Alberta girl clicks in enough to win back the public’s trust that the government is listening while it leads.

Chrystia Freeland has risen to new heights. Everyone knows she may go higher. It’s an impressive story. We should count ourselves lucky that she had a hankering for home.

Contributing Writer Jeremy Kinsman is a former Canadian ambassador to Russia, and the EU, and high commissioner to the U.K. He is a distinguished fellow of the Canadian International Council.