The Longest Month

Douglas Porter

March 31, 2023

After a tumultuous month and a comeback week, equity markets find themselves higher today than at the start of March. Beyond modest monthly gains, the MSCI World Index managed to grind out a 5% advance for all of Q1. As one sly commentator suggested, markets believe things will be so bad that the Fed will need to cut rates in the second half of the year, yet not so bad as to prompt investors to sell stocks. Amid this week’s much-improved market mood, the pressing question is whether this is the calm after the storm, or perhaps the eye of the storm? It certainly appears that the acute phase of the banking stress is behind us, but now we await the potential after-shocks, notably through the credit channel.

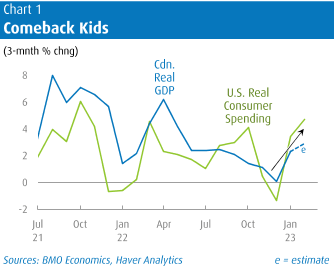

Even as many are looking forward for signs of a potential hit to growth, the rear-view mirror is showing evidence of surprising economic resiliency through the first quarter of the year. For example, U.S. consumer confidence perked up in March, according to the Conference Board, with sentiment for all of Q1 at its best level in a year. Initial jobless claims remained doggedly below 200,000 for most of the quarter, or about 10% below last year’s average level. The consumer is the big story, as even with a small correction in February, an early-year blastoff suggests that real consumption rose at a better-than-4% clip in Q1. As a result, we are boosting our U.S. GDP estimate for the quarter to a 2.0% annual pace, which lifts the full-year estimate three ticks to 1.0%.

The faces and the names are a bit different in Canada, but the end result is the same for GDP. A freakishly mild January helped drive a 0.5% jump for the overall economy in that month, but the big surprise was the lack of a reversal in February. The flash reading was +0.3%, prompting us to crank up our estimate for all of Q1 by a whopping 1.5 percentage points to 2.5% annualized growth. In turn, that boosts our annual call to 1.0%. While the first quarter was much stronger than the Bank of Canada anticipated (it had estimated just 0.5% growth), our revised annual figure happens to fit their latest number to a T.

The faces and the names are a bit different in Canada, but the end result is the same for GDP. A freakishly mild January helped drive a 0.5% jump for the overall economy in that month, but the big surprise was the lack of a reversal in February. The flash reading was +0.3%, prompting us to crank up our estimate for all of Q1 by a whopping 1.5 percentage points to 2.5% annualized growth. In turn, that boosts our annual call to 1.0%. While the first quarter was much stronger than the Bank of Canada anticipated (it had estimated just 0.5% growth), our revised annual figure happens to fit their latest number to a T.

Putting that upward growth revision for 2023 into context, note that this week’s federal budget was based on a conservative assumption of just +0.3% for real GDP this year. One of our main quibbles with the budget plan was that it allowed the fiscal anchor to slip in the coming year—that is, for the debt/GDP ratio to rise by more than a point to 43.5%. At a time of full employment, and when inflation is the economy’s public enemy #1, the net new spending of about 0.2 ppts of GDP in FY23/24 did not look entirely appropriate. If we add in the so-called grocery rebate, as well as net new measures from the provinces, the total net fiscal stimulus from this year’s round of budgets comes closer to 0.5 ppts of GDP for 2023. If the upside surprises to growth continue to roll in, it is still entirely possible that the debt ratio does not rise in the coming fiscal year.

What do these upside revisions do for the outlook for central bank policy? Probably not much, at least not yet. First, our new estimates are not much different from official forecasts. For instance, last week’s FOMC revealed that the SEP had shaved the 2023 Q4/Q4 GDP call by just a tenth to 0.4% (our call translates into a milder 0.1% rise on that basis). In other words, the Fed is still a bit more optimistic than we are, at least officially. And, as noted, our revised call leaves us right in line with the BoC’s view. Second, both central banks will be closely monitoring for any signs that credit is tightening in the wake of the banking stress.

The wait won’t be long in Canada, as the Bank’s quarterly Business Outlook Survey lands on Monday. It includes a question on credit conditions, which were already flagging a significant tightening in the past year (amid the steep back-up in rates). However, the timing of the survey was likely a bit early to have caught the full flavour of the recent strains. We’ll also get a (very) early read on how the economy held up in the midst of the turmoil, with March jobs due on Thursday, auto sales earlier in the week, and home sales from the major cities sprinkled in between. Our assumption is that there won’t be a major break signalled for growth yet, with employment expected to grind out a moderate gain and auto sales supported by improving availability of supplies.

Markets will have to wait one day longer for U.S. payrolls, which will be released on Good Friday this year (thus producing the rare case of Canadian jobs arriving earlier). We expect it will be worth the wait, with a solid gain of around 240,000 likely on tap, lifting the tally for all of Q1 to above 1 million net new jobs—making a mockery of recession talk, at least at the start of the year. While a slight sag in auto sales and the factory ISM is expected, the overall tone for the early read on March is expected to be generally firm in the face of the banking sector strains.

The reasonably positive news for Q1 doesn’t end in North America. The mild winter and the big pullback in energy prices clearly helped Europe avoid the worst-case scenario, and have greased a steep slide in inflation. The Euro Area CPI fell to a much more manageable 6.9% y/y pace in March from 8.5% the prior month, a record one-month step down. While core trends are still headed in the wrong direction, nudging up to 5.7% (versus 5.5% in the U.S.), the break in headline inflation is nevertheless a massive relief for consumers.

Finally, China is dealing with an entirely different set of concerns, including a cooling in its manufacturing PMI amid slowing global growth. But we would highlight the 12-year high in the non-manufacturing PMI as a sign that the domestic economy is snapping back with purpose amid the re-opening. This will help with the transition to a greater focus on internally-generated demand, as the global trade outlook turns much frostier amid the push for friend-shoring elsewhere.

If you think this felt like a very long month, it’s more than just your imagination. There is only one month that can ever possibly have as many as 23 workdays (at least in Canada) and that is March. The reason? It’s one of the seven months with 31 days of course, and it’s the only one of the seven that doesn’t (typically) have a statutory holiday in it. But to hit the cherished mark of 23 workdays, the month also has to start on a Monday, Tuesday or Wednesday, and Easter can’t be early…and this year satisfied all conditions. So, this is one of the four times in a typical decade to have the wonderful confluence of events to produce a 23-working day month. Add in a banking crisis to make it seem doubly long and suffice it to say that was one special month.

Technically, the U.S. can also have a 23-workday August, with no set holidays in that month, and this year fits the bill (starts on a Tuesday). But that month is always welcome to go on for as long as it wants.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.