The Life and Work of One Great Canadian Cartoonist—by Another

Terry Mosher

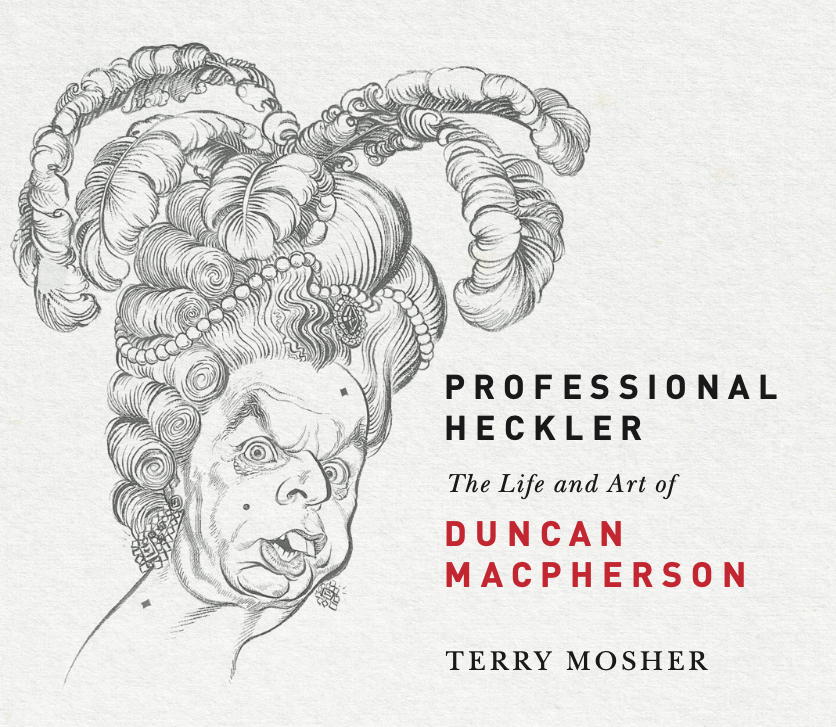

Professional Heckler: The Life and Art of Duncan Macpherson.

Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press, 2020

Review by James Baxter

Duncan Macpherson was not just one of the greatest political cartoonists in Canadian history. He might have been one of the best and most innovative to ever to pick up the mocking pen.

Duncan Macpherson was not just one of the greatest political cartoonists in Canadian history. He might have been one of the best and most innovative to ever to pick up the mocking pen.

His genius is slowly revealed, often inadvertently in his own words, in a new biography Professional Heckler: The Life and Art of Duncan Macpherson, written by another brilliant Canadian cartoonist, Terry Mosher, better known to Montreal Gazette readers, among others, as Aislin.

“Drawing was as natural to me as breathing,” Macpherson once wrote of his ability to draw quickly and well. On another occasion, when asked about his penchant for finding humour in the mundane, Macpherson said: “I taught myself how to see.”

Through cheerful anecdotes and a deft recounting of the events of the era, Mosher takes readers on the journey during which Macpherson created many of the most iconic political cartoons from what was the heyday of Canadian journalism.

From his days drawing planes to teach RCAF pilots to spot the difference between a Messerschmitt and a Spitfire in the Second World War to his skewering caricatures of stodgy Canadian politicos from the late 1950s until his death in 1993 at 69, the genius of Macpherson’s snark and meticulous use of detail is evident in the hundreds of sketches and finished cartoons that Mosher has curated.

What makes Professional Heckler so engaging is the sense that it is written by no less a talent. It’s as if Mario Lemieux were recounting the life story of Wayne Gretzky. With similar talents and demons, and both products of the same high school art program in Toronto, Mosher brings a blend of reverence, gratitude, envy and understanding of “Dunc’s” career and often-mercurial life that only someone with five decades in the cartooning trenches could. The two were sometimes colleagues, sometimes rivals. They were both high-functioning alcoholics, and while Mosher eventually chose the path to recovery, Macpherson never saw the need.

Often in spite of himself, Macpherson became one of the most innovative and subversive of Canadian artists. Recognized as a genius by author and Toronto Star editor Pierre Berton, Macpherson was given the opportunity to create some of the most memorable symbols of political history. He often placed his bespectacled and bedraggled John Q. Public at the centre of his art, giving his readers a direct attachment to what they were seeing. He rarely drew Liberal prime minister Lester Pearson without his “scandal albatross” following closely on his heels. His cartoons of Pierre Trudeau also betrayed an inner conflict that many Canadians shared over the prime minister’s panache and intellect juxtaposed with his breathtaking arrogance.

While cartooning became his day job, Mosher makes it clear that it would be an injustice to dismiss Macpherson as simply that. In detailing Macpherson’s time working in Toronto’s famed Studio Building, where he rubbed shoulders with many of the greats including many remaining members of the Group of Seven, Mosher makes clear that Macpherson was a singularly talented artist and had he chosen a different path, he might well have been regarded as one of Canada’s best ever. One example of Macpherson’s skills as an artist that served him well in cartooning was his remarkable ability to draw the backs of people’s heads and have them be immediately recognizable, which gave those cartoons an immersive feel.

While his bread and butter was Canadian politics, Macpherson had a broad fascination with international affairs. He made multiple trips to Cuba, China and Russia and was able to depict them in wonderful drawings that humanized those caught in the middle of superpower struggles. Scarred by what he and his friends had witnessed in the Second World War, his cartoons of conflict grew darker as Korea led to Vietnam, to the Middle East and eventually to the Gulf War at the very end of his life.

From the book’s foreword by John Honderich, the former editor and publisher of the Toronto Star, through to its last pages, what is revealed is that there was far more to Duncan Macpherson than what was printed on tomorrow’s fish wrapper. He was a brilliant and skilled artist, as adept with a brush as a pen. He was also a chameleon, capable of quickly adapting to new political and business situations. At a time when most sought lifelong jobs with one company, Macpherson was among the first to realize he could make more money (and have more fun) as an independent contractor.

Of course, no Canadian political icon took more of the brunt of Macpherson’s lampooning than former prime minister John Diefenbaker, whose sagging jowls, buck teeth and wild eyes proved irresistible. From the moment Diefenbaker scrapped the Avro Arrow, his popularity began to wane. But many point to Macpherson’s most famous and irreverent cartoon depicting Dief as a callous Marie Antoinette as the shove that began the populist’s slide into political ignominy.

While some thought Macpherson’s caricatures of politicians bordered on cruel, he (usually) respectfully disagreed. He said he aimed his humour to be “devastating without wounding” those in his crosshairs. And, for the most part, his aim was true. The same could be said of Mosher’s book. It is both a lighthearted visual romp through Canadian history and a nuanced, honest look at the life of a deeply complicated and gifted artist.

James Baxter, founder and former Editor of iPolitics, is a lifelong aficionado of Canadian political cartooning.