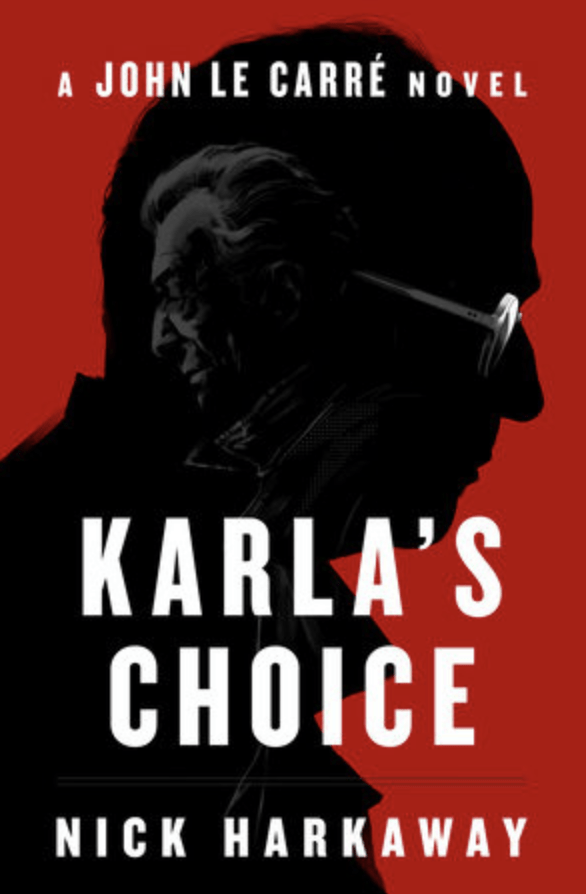

With ‘Karla’s Choice’, Harkaway Deftly Fills a Le Carré Gap

By Nick Harkaway

Penguin Random House/October 2024

Reviewed by John Delacourt

December 22, 2024

A word to the uninitiated: John Le Carré’s Karla Trilogy is named not for a femme fatale or a Mata Hari, but for the code name of the male head of the Soviet intelligence Thirteenth Directorate of Moscow Centre, Le Carré’s version of the KGB. He is also the Cold War nemesis of George Smiley, Le Carré’s most famous protagonist.

Smiley is, per Le Carré’s description, a kind of anti-James Bond: in his 50s, with owlish glasses, a paunch and a donnish love of German literature and Mahler. Karla is the ultimate Soviet operative, a force in Smiley’s life through proxy outcomes and spooky action at a distance. Or, as Anatole Broyard wrote of the characters in The New York Times in 1982: “Short, fat, nearsighted, badly dressed and unlucky in love, yet stubbornly intelligent and unshakably moral, Smiley represents humanism. Thin, merciless, ascetic and amoral, Karla is a fanatic, the priest of a new Inquisition. Nothing matters to him but purity of doctrine, a passion for certainty, a Pavlovian hunger for cause, effect and control.” In the series, Smiley is known as “the vicar”, Karla “the priest”.

Dominic Sandbrook, who with fellow British historian Tom Holland hosts the excellent podcast The Rest Is History, recently appeared on The Le Carré Cast, a podcast devoted exclusively to the work of John Le Carré (nom de plume of David Cornwell, who famously traded-in an early career as a spook to write about them). Sandbrook predicted that, in contrast to many of Le Carré’s contemporaries whose postwar work had garnered the most praise, including Sir Angus Wilson and Sir William Golding, the 26 novels of Le Carré — who declined a knighthood and eschewed literary prizes — will survive while Wilson and Golding, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature, will be all-but forgotten.

Sandbrook may be onto something. In 1974, the year Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy was published, the Booker was jointly awarded to Holiday, a novel by British author Stanley Middleton, and Nadine Gordimer’s The Conservationist. But the gritty, darkly Machiavellian plotting of Le Carré’s best novels still resonates enough to merit new print runs, and still tells us something about the geopolitical fault lines that only widened and deepened with the end of the Cold War and the prematurely pronounced End of History.

Patrick Stewart as Karla and Alec Guinness as Smiley in the iconic 1982 BBC production of ‘Smiley’s People’/BBC

Patrick Stewart as Karla and Alec Guinness as Smiley in the iconic 1982 BBC production of ‘Smiley’s People’/BBC

The Karla novels are a unique literary achievement, tracking Le Carré’s restless sense of innovation as the global canvas unfurls for this old conflict. Tinker, billed as a spy thriller, is actually structured like a detective novel, as Smiley investigates just who was for turning among his colleagues in the Circus (the fictional MI6). In The Honourable Schoolboy (1977), the second installment in the trilogy, Smiley is merely an eminence grise of the Circus, leading an investigation that unearths a double agent for Karla. Smiley’s People (1979) is in many ways the defining portrait of Smiley (though he appears in other Le Carré novels), because Le Carré allows his anti-Bond a final victory: Karla’s crossing over from East to West Berlin, and into the hands of the Circus; a powerfully vivid evocation of that moment when the grand narratives on both sides of the Wall begin to crumble as precipitously as that bloodstained monument soon would.

The novels, which were published in omnibus form as The Quest for Karla in 1982 (later re-titled Smiley Versus Karla) are all so distinctly of their time and place in history (ideal complementary reading: Sandbrook’s own Seasons in The Sun) that it would be a daunting task for any author to try to reimagine the dinge and faint air of menace that is there in every page of the trilogy. The tension and suspense are in minor chords rather than the power chords of contemporary spy thrillers.

Enter Nick Harkaway (né Nicholas Cornwell, yes, son of David), four years after his father’s passing. As Harkaway tells it in interviews about Karla’s Choice, it was his wife Clare’s proposal, as the director of John Le Carré Ltd, that he breathe new life into the Smiley franchise. Such an enterprise seemed to be supported by Harkaway’s own promise to his father during a walk on Hampstead Heath that he would finish any work left incomplete at the time of his death. When I first heard this was happening, long before Karla’s Choice was released in October — making the Karla Trilogy the Karla Tetralogy — I was reminded of Martin Amis’s sly retort to insinuations that he was the beneficiary of his father Kingsley’s literary coattails; that writing bestselling novels was “just like taking over the family pub.”

That Harkaway could pick up where his father left off was by no means a sure thing, and there was no guarantee that Karla’s Choice would be any good. And yet, reader, it is.

Harkaway, like Amis fils, has been an author in his own right, albeit at a far greater stylistic distance from his father. He has written eight novels that bore little resemblance to his father’s oeuvre. They are far more speculative, incorporating elements of science fiction and the loopy noir-ish tropes found in Haruki Murakami and Thomas Pynchon. It doesn’t suggest an author who could easily transition to the mode of world building and character development in which his father specialized. That Harkaway could pick up where his father left off was by no means a sure thing, and there was no guarantee that Karla’s Choice would be any good.

And yet, reader, it is.

Wisely, Harkaway has avoided writing a sequel to Smiley’s People. Instead, Karla’s Choice reaches back to the decade between Le Carré’s debut, The Spy Who Came in From the Cold and Tinker, Tailor, Soldier Spy, to fill in a chapter. It is 1963, and here’s how Harkaway describes Berlin:

“Berlin was an island in the East German sea, and only half of it was accessible. You bumped up against edges with surprising frequency. The second thing was colour. The Western zone was almost garish: consciously or otherwise, the inhabitants accented their business clothes with shocks of scarlet and azure; they talked loudly and professed forceful opinions, as if to make the point to others behind the Wall. By comparison, East Berlin was a muted city. Even if you could find brighter colours, you might choose something quieter … the Friedrichstrasse Railway Station, which went to the West, was the truth of the whole damn place; the process of purchasing a ticket and passing through security turned you around and around, so that you might be traveling to the Bundesrepublik but you surely couldn’t point to it with your finger, and the cameras and mirrors looked down on the back of your neck … In the West, colours; in the East, visibility; and in between, the Wall, like a concrete mirror of everything that was wrong with everything.”

Those last two “everythings” have no right to work in that paragraph. But they do, like an evocation of mirroring, and a final dissolution of coherence, the disorienting experience inherent in the transit between the two Berlins. It is a paragraph worthy of Le Carré himself (and there has to be some remnant of field research there, because this reviewer’s own experience of East Berlin just before the Wall came down was eerily similar).

Gary Oldman as George Smiley in the 2011 film ‘Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy’/Focus Features

Gary Oldman as George Smiley in the 2011 film ‘Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy’/Focus Features

In the opening pages, we learn that Smiley is retired and his main focus is a protracted reconciliation phase with his wandering wife, Lady Ann Sercomb. However, Control, head of the Circus, has other ideas; he needs Smiley to investigate the sudden disappearance of Hungarian émigré and publisher László Bánáti. As the investigation progresses, we discover that a Russian agent, Miki Bortnik, had arrived in London to kill Bánáti but lost heart in the mission for some reason (he does state his ambition is to act in a movie with Peter Sellers; it is a comic flourish that shouldn’t work and yet it does because Bortnik is so well-drawn a character).

Bánáti’s assistant, Susanna Gero, is also a Hungarian émigré. As she attempts to find out what has happened to Bánáti, she is recruited by the Circus and the search for Bánáti expands across Europe. Like Le Carré, Harkaway makes this a kind of meditation on the mutability of identities shaped in the catastrophe of conflict and the clash of ideologies that emerged at the end of the Second World War. Smiley’s inevitable re-engagement with Karla is handled with all the rich dramatic irony that defines the Le Carré tone: in a lower, sombre key, the dialogue filtered through that world-weary operational register where betrayal and deception are all but expected, from both victors and vanquished.

The full dramatis personae of the Circus is present and accounted for, Harkaway reimagining 60s versions of them all. Researcher Connie Sachs is full of ambition and bold attitude, and the agent, chancer and womanizer Bill Haydon has free license in a London not quite yet swinging. But it’s in the formative ersatz Englishness of Hungarian emigré-surveillance master Toby Esterhase that Harkaway’s own talent for character development shines.

Outsourcing the posthumous reanimation of an authorial brand is a low-risk proposition for publishing houses, yet the efforts of contemporary authors to fully replicate the fictional worlds of, say, Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe or Ian Fleming’s Bond have yielded mixed results (some standouts are the Marlowe novels of John Banville and Lawrence Osborne or the Bond novels of William Boyd, Sebastian Faulks and yes, Kingsley Amis).

This effort at sustaining the Le Carré franchise could have gone very wrong: the kind of first draft of a Netflix screenplay, all clichés and TV dialogue, that is all-too endemic among contemporary thrillers. Harkaway, however, knowing the stakes for the family trust, went someplace deeper, truer for this reimagining of the Karla novels of his father.

In the process, he has honoured a legacy that still tells us so much about the state of polycrisis we’re in, and the grey men who helped get us here.

Novelist and Policy Contributing Writer John Delacourt is Senior Vice President of Counsel Public Affairs in Ottawa.