The Heart of the Matter for the NDP

“To be Irish is to know that in the end the world will break your heart,” the late Democratic Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan famously said. It’s a sentiment that could easily apply to the federal NDP—the party of idealism over cynicism, of principle over power and other consoling clichés that make Jack Layton’s record-breaking, valedictory blow-out in 2011 all the more poignant. A decade later, Brian Topp, the party’s former national director, has a post-election plan to un-break the NDP’s heart.

Brian Topp

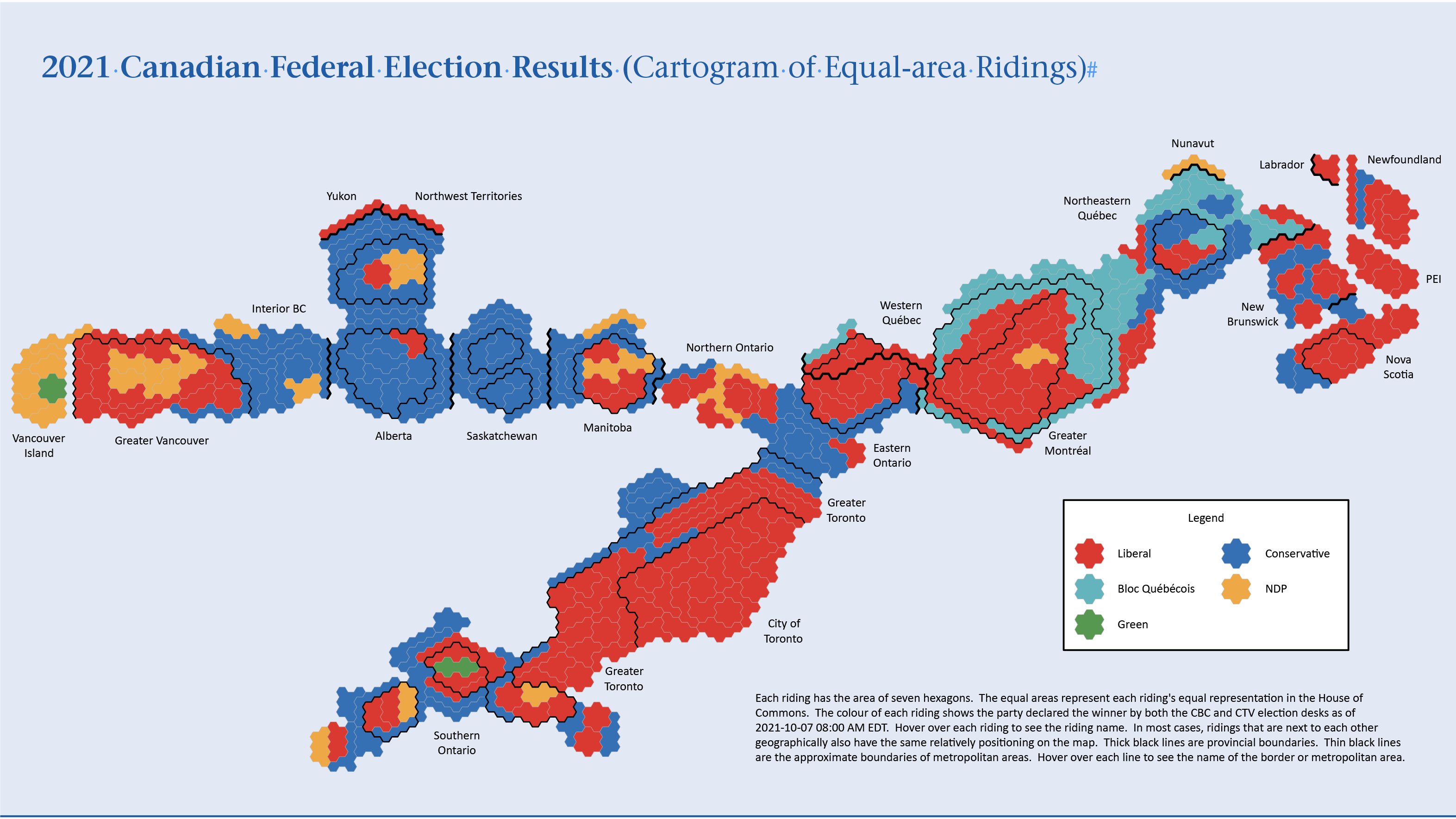

Everything that’s red on this map, make it orange.

That’s what the federal NDP needs to do if it wants to govern, and that’s what it should be aiming for in the next federal election and in every election.

And now, a few words on the details. Let’s begin by praising Montreal software developer Mark Gargul, who designed this map and uploaded it to the Wikimedia commons. Mark’s map reminds us of two things:

First, we still live in a sideways Chile that is in good part built along a couple of railroads. Thank God for Edmonton! How often have you said that? The people lucky enough to live there say it all the time. So do Alberta New Democrats.

Second, parties that sweep Greater Montreal, Greater Toronto and the Lower Mainland of BC get to govern Canada, and parties that don’t—well, don’t.

That is what Canadians handed the Conservatives and the New Democrats in the 2021 federal election. Both have difficult election post-mortems to undertake.

New Democrats can be rueful about what looks like a missed opportunity. In the first week of the 2021 election the NDP was polling at 25 percent and was in contention in over 60 seats. Canadians then listened to the campaigns and their closing arguments, and the NDP’s vote dropped by a third and its potential seat haul dropped by more than half (the NDP earned 17.83 percent of the vote, up 1.8 percent; and 25 seats, up one). Some of the seats the NDP lost were eye-wateringly close, which means they were winnable.

On the other hand, Jagmeet Singh remains Canada’s best-liked and best-regarded federal leader, by far. He is unchallenged in his party. And he emerged from the election holding the same partial-balance-of-power parliamentary cards that Tommy Douglas held in his day. For the federal NDP, alas, that’s pretty good. Now what?

Well, there’s always the merger option, at least as a hypothetical talking point. Should the NDP now give up, and merge with the Liberals? Our editors here at Policy Magazine asked me for a status report on this matter, so here you go:

That’s a tough sell inside the NDP. In most jurisdictions where the NDP has become a party of government, competing provincial Liberal parties have mostly disappeared—an easier formula for getting along than trying to cohabitate in a new party. You can look this up under British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Ending the risk of conservative rule through a single, powerful, merged progressive party is a tough sell inside the Liberal party, too. I asked a friend on the red team to comment and he said this: Liberal party members might not leave “a combined party that would be defined by extremists on the left, but voters would, as they have in all the English speaking democracies, leaving the right to form government most of the time and the left, when it does form government, unable to erect the kinds of lasting reforms the Liberal Party of Canada exists to enact.”

Now, Medicare seems fairly lasting. That was launched in Saskatchewan under a party defined by the left, under Premier Tommy Douglas. And then brought to the rest of Canada when Douglas and Lester Pearson teamed up during a minority Liberal government to get it done. But in any event, as you can see, proponents of this idea have nothing to work with.

Then there’s the “be BOLD” option. In contrast, should the NDP embrace “bold”, “strong” and “courageous” policies, become much more militantly socialist, green, and dirigiste—and finally give a winning plurality of Canadian voters that hard-left federal government they’ve been waiting impatiently for, if only the NDP could figure it out?

I will spare you a discussion of the party’s burdens with Trotskyite groupuscules and lefter-than-thou media showboats. Instead, let’s just say this. In addition to these people, there are also thoughtful activists (many of them young members of the “Layton legacy”) on the left of the NDP who argue cogently that “professionalization”, a focus on good public administration and contesting the centre will never elect the NDP at the federal level.

If voters want a liberal party, there’s already a pretty good one on offer in Canada. Given a choice between two liberal parties, voters will choose the real one, as they did in 2015. The NDP is therefore condemned to be itself, and that means finding an inspiring social democratic/democratic socialist vision that a plurality of Canadians can see themselves in.

Which is not about chanting Trotskyite slogans; and it’s not about shouting a laundry list of BOLD yet somehow boring and impractical proposals. It’s about offering working people a real alternative to a status quo under our current ruling parties that harms the many and coddles the few. And a real alternative to the hateful divisiveness of right-wing populism. In thinking about the future, the NDP needs to listen to its heart on this, and stay in touch with its own values.

Which leaves going for gold, each and every election. Just plain pursuing victory in federal elections with unblinking determination until victory is won, exactly like a post-election tweet by the current national campaign director and federal leader’s chief of staff, Jennifer Howard, who wrote: “We plan to win.” Excellent!

What would going for gold look like for the NDP?

First, determination is required. Political parties that challenge Canada’s since-pre-Confederation ruling tradition have their work cut out for them. The B.C. CCF/NDP ran in 12 elections under various leaders before winning office under Dave Barrett in 1972. It took 20 tries for the Alberta CCF/NDP until Rachel Notley in 2015; only two for the Saskatchewan NDP until Douglas in 1944; 14 campaigns in Manitoba until Ed Schreyer in 1969; 15 in Ontario until Bob Rae (always an asterisk on that one—that government’s real record merits a re-examination); and 24 efforts in Nova Scotia until Darrell Dexter. In other words, don’t give up.

Second, victory for the federal NDP runs through Quebec. Progressive English Canadians, especially in Ontario, will not elect a government that is not a national party. And English Canada’s progressive majority won’t risk Tory rule by voting for the NDP until they believe it can win. Look at Mark Gargul’s map. What portion of that ocean of red in Canada’s urban majority is going to switch to orange and get the dominoes falling? More than likely, Montreal would be first. Quebecers have already demonstrated their willingness to switch to orange, as they did under Jack Layton, giving him 43 percent of the Quebec votes and 59 seats in 2011. Le bon Jack took to the NDP to Official Opposition. In the right circumstances they might do so again. And then that tantalizing 25 percent at the start of a campaign becomes 30 percent after the leader’s debates and a winning 35-40 percent after a successful cross-Canada closing argument (absent in almost all NDP campaigns).

How to make that happen? The federal leader is going to need to do what Jean Charest, Lucien Bouchard and many other aspiring Quebec leaders did—go talk to Quebecers, francophone Quebecers, in dozens of events, often to small audiences, in cities and towns all across Quebec. Also, be present in the French-language media—every week. Then, focus on issues that French-speaking Quebecers and English-speaking progressives can agree on and would want to work together on—equality and climate change, for example—and not on the symbolic issues the populist right uses to divide people. And recruit candidates early and get them and their campaigns up and running a year or two before the election, and not a week or two after the writ drops.

Third, then do the same things across Canada, beginning in the GTA, the Lower Mainland, the prairies, and among new Canadian communities.

Fourth, campaign better. A coming post-mortem will look at the 2021 campaign—and, hopefully, at the federal party’s organizationally comatose state between elections. There’s a lot to talk about at the national, provincial and riding level.

Fifth, victory for the NDP requires it to re-connect with working people. It’s not a coincidence that Erin O’Toole and his team explicitly targeted working people with proposals the NDP would do well to consider. Conservatives of all stripes can see that progressive parties like the NDP are at risk of losing touch with their base—and that the blue team might find their winning margin there. Responsible Conservatives, like the latest version of O’Toole, are pitching for those votes with sensible proposals. Vicious populists like Trump and the world’s micro-Trumps appeal to ethnic hatred, climate change denial, anti-vax madness, and the rest.

In every democratic country in the world, parties on the left are wrestling with these same political risks. German Social Democratic Party leader Olaf Scholz recently came out on top in the German election by persuading a plurality of voters that he was the most competent candidate for chancellor, a formula that should work well for Rachel Notley fairly soon in Alberta. He also won by reframing his party’s appeal to its working family base by saying that it is time for working people to be respected again. Respected in meaningful ways—in their income, in their treatment on the job, in access to housing. That was smart because it was an emotional appeal, not a laundry list of uninspiring spending proposals. And it was an effort by a leftist party to put working people at the heart of its campaign instead of threatening their jobs, insulting their values, and implicitly inviting them to look for advocates elsewhere.

That is the heart of the matter for the federal NDP in Canada. The NDP needs to listen to its heart and remember who it is. And it needs to appeal to the hearts as well as the heads of a winning plurality of Canadians, beginning with its own base.

Contributing Writer Brian Topp is a former NDP party president and served as national campaign director under Jack Layton. He was chief of staff to Alberta Premier Rachel Notley. He teaches at the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University, is a partner at GT & Company, and chairs the board of the Broadbent Institute.