The Global Pause that Refreshes

Douglas Porter

November 3, 2023

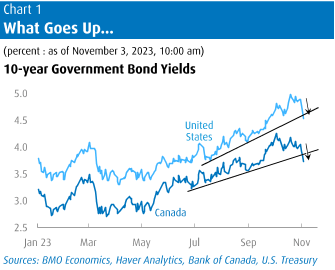

When we all look back at this highly unusual and extremely eventful cycle, it may be no exaggeration that this week will be viewed as a watershed. A confluence of major events came together in recent days to apparently break the fever in long-term interest rates, the U.S. dollar, and perhaps even bearish sentiment among consumers and businesses. The major spark was Wednesday’s FOMC meeting, which helped drive a 40 bp plunge in 10-year Treasury yields over a matter of three sessions. After piercing the 5% level only recently, this week’s huge rally took them down below 4.5% before bouncing slightly. Global bonds came along for the ride, with bunds falling 30 bps in little more than a week, and Canada nearly keeping pace with the steep U.S. decline—10-year GoCs fell to barely above 3.7% after pushing above 4.25% just one month ago.

The sharp pullback in long-term interest rates was a profound relief for struggling equity markets, and particularly for dividend-heavy and long-duration stocks. After suffering through a 10% correction in the past three months, the S&P 500 snapped higher by roughly 5% this week, while the lagging TSX was headed for its best week in more than a year with a near-6% advance. At the same time, the U.S. dollar finally relented on its upward march, retreating against a broad basket of currencies. Even the Canadian dollar got into the act, rising 1.5% from last Friday’s low tide—i.e., the very day that we penned a piece on the plight of the loonie. Mostly anticipating such a turn, and in our sturdy defence, we did not change our outlook on the Canadian dollar, and continue to expect it to firm over the next year as the greenback fades further.

Yet while this week may mark a watershed, we can forgive future financial historians from wondering precisely what the trigger was for such widespread jubilation. After all, the Fed’s decision to pause was not new—it’s the third FOMC meeting this year on hold—nor was it the least bit surprising, as Fed speakers had well-telegraphed the outcome. Some pointed to the mention of tighter financial conditions in the Statement, but many, many Fed officials had noted that in recent weeks. (As well, the furious rally of recent days has gone a long way to reversing said “tighter” conditions.) And Chair Powell’s remarks at the press conference were appropriately guarded, with precisely zero promise that the Fed was done. Even so, markets have almost fully priced out any odds of additional hikes and are expecting cuts by the middle of 2024.

This week’s heavy onslaught of economic data was not especially shocking either, although the skew was fairly consistently to the soft side of expectations. Friday’s jobs report for October was arguably the perfect tonic for an ailing market. We will studiously refrain from the tired cliché of calling it a Goldilocks result, even if it was neither too hot—hourly earnings cooled to 4.1%—nor too cold—job gains were still 150,000—but just right: the unemployment rate nudged up a tenth to 3.9%. Papa bear may note that the household survey, which often catches turning points earlier than its payrolls sibling, reported a deep 348,000 job loss. Besides a cooler jobs result, both the factory and services ISM came in well light of expectations, reinforcing the view that GDP will decelerate noticeably in Q4 after the 4.9% Q3 blowout. We remain comfortable with our call of just under 1% this quarter; and note that the Atlanta Fed’s early read on its GDPNow is 1.2%.

Treasury’s quarterly refunding was also a key focus this week, and even it helped lighten the mood in the bond market. Make no mistake: Funding requirements remain onerous, with the underlying budget deficit running at nearly $2 trillion. But next week’s slate of three major auctions will haul in $112 billion, a bit less than the market was braced for heading into the announcement.

The better news for bonds was not exclusively a U.S.-driven story. Last week saw both the Bank of Canada and the ECB also choose to pause, while the Norges Bank and the Bank of England joined the cool kids on the sidelines this week. Actually, the truly cool kid is the central bank of Brazil, which led on the way up and slashed its Selic rate 50 bps this week, the third such cut this year.

The decision by many major central banks to hit the pause button reflects local economic realities. To wit, this week alone saw Euro Area GDP fall 0.1% (not annualized) in Q3, and it is now up a meagre 0.1% in the past year. The region’s inflation rate encouragingly came in well below expectations at 2.9% last month, the lowest in more than two years and well below trends in other major economies. Before breaking out the bubbly, note that this friendly reading was aided by removing the ugly base effects of a year ago, when natural gas prices were exploding higher. The two-year trend in Euro Area inflation is still lofty at 6.7%, while it’s below 6% in North America. Still, the three-month trend in core inflation has dipped below a 3% annualized pace, and a slight upward nudge in the jobless rate to 6.5% suggests the heat is off.

Canada added to the bond bullish sentiment. GDP remains in a funk, with flat the new up. After a burst of activity in the opening month of 2023, the Canadian economy has since seen essentially no growth, as measured by the monthly GDP reports. Some analysts point to a series of special events as causing the prolonged lull, but that excuse wears thin after eight months of no growth. Canada may not be in a recession, but it’s the next worst thing. The employment report reinforced the point, as the jobless rate rose another two ticks to 5.7% in October, even as the economy managed to add 17,500 jobs. But with raging population growth, that’s simply not nearly enough to keep the labour market from softening on net—the economy now requires about 50,000 new jobs per month to keep the unemployment rate stable. Adding insult, all of the latest jobs were part-time positions, keeping total hours worked steady.

The Bank of Canada thus now looks more firmly pinned to the sidelines. While Governor Macklem sounded somewhat even-handed last week, he has also more openly talked about what could start to bring rates down, and how we don’t need to see inflation back at 2% to begin the proceedings. The modest recovery in the Canadian dollar in the past week also removed a pressure point on the Bank.

Similar to the U.S. pricing, markets are now spying the middle of next year as a logical starting point for rate relief from the Bank of Canada. We would largely concur, although the risk remains to a bit later, given the underlying stickiness of inflation. The reality is that 4.8% wage growth, coupled with no productivity growth whatsoever (see below), is still a threat to sustaining inflation. Most short-term measures of core inflation are still running close to a 3½% annualized pace, outside of the Bank’s comfort zone. Like many other central banks, this pause that has refreshed could turn into a lengthy sabbatical.

This week’s Focus Feature (for November 3) takes a deep dive into Canada’s woeful productivity performance. Here’s an excerpt from “Canada’s Perennial Productivity Puzzle”:

It’s not news that Canada’s productivity performance is listless and lagging U.S. trends. That has been going on for decades. But what is news is that productivity has actually gone into reverse in the past five years—i.e., it has declined, taking real GDP per capita with it on a downward path. The sustained decline in recent years is without precedent in the post-war era. And we can’t (entirely) blame the pandemic for the recent sickly productivity trends, as the U.S. has managed near-normal growth, on average, over the past five years. To be clear, productivity is not simply some obscure, esoteric statistic that only academic economists would care about; GDP per hour worked is the very fundamental building block of living standards. Thus, the recent fall in productivity is stark evidence that Canadians on average are worse off than prior to the pandemic—it’s not just perception.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.