The G7 Cornwall: Back to Normal, with Key Upgrades

G7 finance ministers meeting in London ahead of the Cornwall G7, June 5, 2021/Reuters

Colin Robertson

June 7, 2021

This coming weekend, the leaders of the advanced economies and leading democracies will meet at the Carbis Bay Hotel in a tiny Cornish seaside village in Britain’s most southerly county. While the agenda has evolved annually since its creation in 1975 (Canada joined in 1976) in the wake of the oil shock crisis, the G7 leaders have had two overriding priorities: strengthening the global economy and bolstering the rules-based order.

For this meeting, host British Prime Minister Boris Johnson has also invited the leaders of, India, Australia, South Korea and South Africa to Carbis Bay. Together, the 11 leaders represent almost two-thirds of the people living in democracies around the world.

The leaders meet against a challenging backdrop. In a signed statement released June 3rd and titled Our Planet, Our Future: An Urgent Call to Action to the G7, 126 Nobel laureates called on the leaders to commit to “a new relationship with the planet” recognizing that this decade will be “decisive” in determining whether the Earth remains habitable.

As host, PM Johnson has set a high bar, declaring that “as the most prominent grouping of democratic countries, the G7 has long been the catalyst for decisive international action to tackle the greatest challenges we face.” Johnson wants to ‘build back better’ from the pandemic by:

- leading the global recovery from coronavirus while strengthening our resilience against future pandemics

- promoting our future prosperity by championing free and fair trade

- tackling climate change and preserving the planet’s biodiversity

- championing our shared values

The leaders’ summit is the culmination of a yearlong process of meetings including seven ministerial tracks: foreign, finance, transport, development, education, health and environment. A comparison to an iceberg is apt: if the summit is the tip and most visible piece of the G7 process, this coordinated process of ministers and officials lies mostly beneath the surface of public attention but it is vitally important. There is also significant civil society outreach involving the Gender Equality Advisory Council and the G7 engagement groups: Business7, Civil7, ThinkThank7, Labour7, Science7, Women7 and Youth7.

The G7 leaders met virtually in February when PM Johnson convened them on the pandemic. They agreed to “build back better for all” – the theme of this year’s conference — through addressing climate change and the reversal of biodiversity loss, and committing to “levelling up our economies so that no geographic region or person, irrespective of gender or ethnicity, is left behind.”

Carbis Bay will be Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s fifth G7 summit, and from there he will go to Brussels for the NATO summit (June 14) and then the Canada-EU summit (June 15) before returning to Canada to quarantine. After Chancellor Angela Merkel, who steps down this fall, Trudeau is the longest-serving member of the current G7 leaders’ club.

Trudeau hosted the 2018 Charlevoix G7 summit, which emphasized gender equality and the empowerment of women, combating the climate crisis, ridding the oceans of plastic, and defending the rules-based international order. These themes remain on the G7 agenda, the latter given particular prominence by US Secretary of State Antony Blinken at the foreign ministers’ ministerial in London, where he singled out “defending democratic values and open societies” as an agenda item amid systemic threats from China and Russia.

Trudeau will continue to press for action on Canada’s agenda, including through the Gender Equality Advisory Council, established at Charlevoix. Its work is incremental but continuous, like the G7 itself. Another example is the Oceans Plastics Charter, also discussed at Charlevoix, that continues to expand its signatories to global partners like IKEA and Walmart.

Success at Carbis Bay will be measured not just by the post-Trumpian dynamic with President Joe Biden in the American seat — who can forget Angela Merkel staring downDonald Trump at Charlevoix? — or their communique (without Trump there will be one) but by their actions and follow-up. More people may work on the draft of the final communiqué than will read it but the process of getting there is what really matters. The ongoing meetings between the leaders’ Sherpas and relevant ministers, keep the dialogue going.

Deliverables come in two parts. There are the useful initiatives like the ongoing work on gender. Then there are the top-table agreements on critical issues hammered out in their face-to-face formal and informal discussions.

A good example is the work of the finance ministers to reform, as Britain’s Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak put it: “A tax system that was largely designed in the 1920s.” G7 Finance ministers agreed June 5 to a minimum global corporate tax rate of at least 15 per cent, designed, per Chancellor Sunak, “to reform the global tax system to make it fit for the global digital age.” Agreement at Carbis Bay would give the proposal momentum for October’s G20 summit in Rome.

Deliverables come in two parts. There are the useful initiatives like the ongoing work on gender. Then there are the top-table agreements on critical issues hammered out in their face-to-face formal and informal discussions. The extent and number of these commitments is their test at Carbis Bay. Can they find consensus in a shared communiqué that they then translate into legislative and regulatory actions?

A favorable verdict on Carbis Bay will hinge on three big issues – COVID recovery; climate; and defending the rules-based international order.

On COVID, can the democracies collectively act to vaccinate the rest of the world? The International Monetary Fund wants a commitment to vaccinating at least 40 percent of the population in all countries by the end of 2021 and at least 60 percent by the first half of 2022. Debt relief for poorer countries also needs firm commitments. Debt relief, increasing vaccine production, then getting the actual jabbing done would give credibility to the G7 summit theme of “Building Back”. G7 militaries, especially the US divisions that helped contain Ebola in Africa with Operation United Assistance in 2014, should play a key first-responder role – which will no doubt be discussed at the NATO summit on June 14.

On climate, it is a question of ambition. Looking to the Glasgow climate summit in November, G7 environment ministers have already committed to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 at the latest, with deep emissions reduction targets in this decade. Building on the 2018 Charlevoix commitments, they have also agreed to conserve at least 30 percent of the world’s land and ocean and to bend the curve of biodiversity loss by 2030. The recent Peoples’ Climate Vote, the world’s biggest-ever survey of public opinion on climate change, revealed that over half see climate change as a “global emergency”. As customers, shareholders, and the courts weigh in over climate change, business now routinely factors environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) into their investment calculations. These ideas are explored by UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance Mark Carney in his new book Values, that draws on his 2020 Reith Lectures in which he argued that the shift from market economies to market societies helped spawn the crisis of credit, climate and COVID. For Carney, a “strategy of relentlessly focusing on decarbonization across the economy while achieving commercial returns for investors” is doable, necessary and will generate new prosperity.

On China, President Biden has framed it as a battle between the “democracies and autocracies…We’ve got to prove democracy works.” Public opinion in G7 nations has shifted significantly in recent years, with at least seven in ten having a negative view of China. In their meeting last month, G7 foreign ministers called on China to follow global rules on trade and to respect human rights, specifically pointing out its violations in Xinjiang, Tibet and Hong Kong. In a coordinated move, Canada, the UK, USA and EU imposed sanctions over Xinjiang, but more targeted action needs to be applied. The G7 actions on China and Russia will condition the discussion at the NATO summit.

After four years of a disruptive Donald Trump, the other leaders will also be assessing whether Biden’s presidency means that the US is really “back” and ready to lead the democracies. The Trump experience showed that without American leadership, the democracies drift. Despite efforts, especially by the Germans and French in creating the Alliance for Multilateralism, there is really no plausible alternative to US leadership, especially when it comes to security.

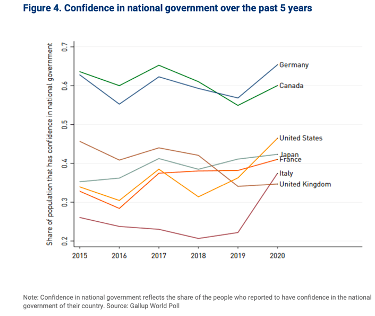

The pandemic has created greater confidence in governments. Can the G7 leaders come to a consensus on climate, energy, protectionism, populism and extremism? If we are moving into an economic decoupling with China, then supply chain resilience will need the G7’s ongoing attention.

At this, their 47th summit, it is easy to be cynical about the G7 and to regard it as “an artifact of a bygone era”. With no members from Africa, Latin America or the southern hemisphere it also faces a challenge from fast-growing emerging economies, such as India and Brazil, that may outstrip some of the G7 nations by 2050.

But in turbulent times, there is real value in leaders of the world’s largest advanced economies, who share the values of freedom, democracy, the rule of law, and human rights, getting together to discuss shared concerns. As Canada’s former long-time Sherpa, and now chair of the Senate Foreign Affairs committee, Senator Peter Boehm, observed: “The G7 is a collective, it’s not a global government. Yes, we’re going to have differences — we wouldn’t be having these meetings if we were all agreed on everything … The leaders are really only together for about 48 hours, so are we going to solve all the problems in the world? No. Can they have a good discussion and push things forward? Yes. Can they convince some of the more recalcitrant leaders that maybe they should be a bit more open-minded? There’s a good possibility of that too.”

Winston Churchill, who popularized the word “summitry”, observed that “jaw-jaw” among leaders is better than “war-war” and with trade conflicts on the rise within the G7 partnership they need to talk. Frank discussions and informality characterize the G7 summits. Multilateralism needs constant reinvigoration and through its multiple ministerial tracks and annual summit, this is what the G7 is all about.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former foreign service officer who served in New York (UN and Consulate General), Hong Kong, Los Angeles and Washington, is Vice President and Fellow of the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.