The Fury of an Aroused Humanity: Why D-Day Still Matters

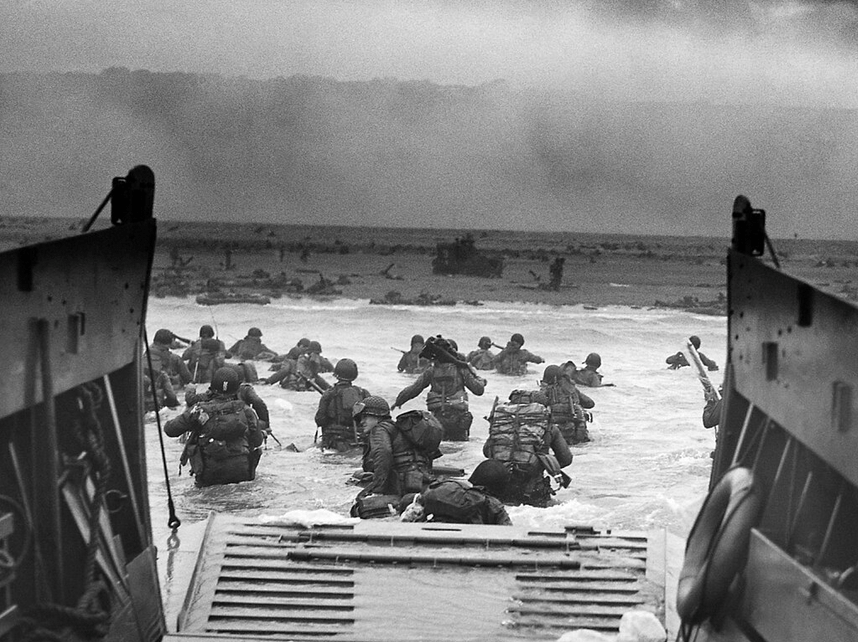

The iconic D-Day image ‘Into the Jaws of Death’, taken at 7:40 am local time on June 6, 1944, by Robert F. Sargent, a chief photographer’s mate in the U.S. Coast Guard/USCG

The iconic D-Day image ‘Into the Jaws of Death’, taken at 7:40 am local time on June 6, 1944, by Robert F. Sargent, a chief photographer’s mate in the U.S. Coast Guard/USCG

By Lisa Van Dusen

June 5, 2024

Looking back at June 6th, 1944 from 80 years’ distance, D-Day was many things — a legendary logistical feat, a military success, a seaside charnel house, a strategic triumph, a before-and-after delineation both for the loved ones around the lives it ended and in the war it helped end.

It was also, for better and worse, supremely human. It wasn’t a blow against tyranny delivered by drones, by hacked power grid, by economic blockade, or by the indifferent miasma of a radioactive cloud. The rows and rows of alabaster headstones of the D-Day dead in the humbling, breathtaking Canadian War Cemetery at Bény-sur-Mer attest to that.

It wasn’t a fatal blow landed against the domination fantasies of a madman made real via waves of counteractive industrialized deception; it was delivered via waves of members of precisely the same species Adolf Hitler had been terrorizing, subjugating and systematically annihilating.

“War turns people into numbers,” Ukrainian peace activist and Nobel laureate Oleksandra Matviichuk said about Vladimir Putin’s illegal war against Ukraine in an interview with Policy published this week. “The scale of war crimes grows so fast that it becomes impossible to tell all the stories. But people are not numbers.”

When we think of the stories of D-Day, we picture, mostly in black and white, tempest-tossed landing craft full of men — so many, so young, weighed down by weapons and backpacks, looking tough but surely terrified, knowing they may soon, of necessity, become numbers.

While the tactical calculus of this operation was incredibly intricate, the old math behind its immediate success or failure hinged on an inevitable percentage of mortal sacrifice — including among the 14,000 Canadian volunteers landing on Juno Beach, so christened after Winston Churchill deemed “Jelly” too frivolous a fish for a Canadian Gettysburg.

Our Policy series on the D-Day 80th Anniversary includes a piece by Historica Canada President Anthony Wilson-Smith about Maj. Archie MacNaughton, the soldier whose story was told in the 2019 D-Day Heritage Minute to exemplify the bravery and sacrifice of the 1,083 Canadians who were killed in action on D-Day along with him.

Maj. Archie MacNaughton, standing, second from right, two days before D-Day/MacNaughton family

Maj. Archie MacNaughton, standing, second from right, two days before D-Day/MacNaughton family

“This has been a busy time, but I am awful glad I was in it,” Maj. MacNaughton wrote to his wife back in Black River Bridge, New Brunswick, on June 4, 1944. “No matter how things go, Grace, life has been very kind to us.” Two days later, he survived the landing but not the liberation of Tailleville, a village with more Nazis than residents, as the local chateâu had been requisitioned as the SS Kommandatur. MacNaughton was shot dead 4,663 km from home and 4 km from Bény-sur-Mer, where he is buried. He was 47, the oldest Canadian soldier killed on D-Day.

You don’t need to imagine why what, to us, seems like a suicide mission was seen by its human assets as a moral imperative. There are more than enough quotes on that question from survivors. Most, in essence, echo the words of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Canadian nurses arriving in Normandy/LAC

Canadian nurses arriving in Normandy/LAC

“They fight not for the lust of conquest,” FDR said in his radio broadcast hours after the invasion. “They fight to end conquest. They fight to liberate.”

Two and a half years earlier, when, after Pearl Harbor, America had finally entered the war, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower wrote to his brother, “Hitler should beware the fury of an aroused democracy.” By D-Day, it was the fury of an aroused humanity.

Just as indelible today as that rage — so painstakingly preserved in countless documentaries and fictionalized accounts, from Cornelius Ryan’s The Longest Day to Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan — is the culture of wry defiance that accompanied it. It’s there in the scene from David Halton’s piece in our series — Courage and Calvados: The Canadian Correspondents Who Covered D-Day — where his father, legendary CBC war correspondent Matthew Halton, with Reuters man Charlie Lynch on piano, leads a shipboard Vera Lynn singalong with Canadian troops headed for Juno Beach.

It’s there in the screw-Hitler langour, the anthemic buildup of that unlikely, exquisite battle hymn, Glenn Miller’s Moonlight Serenade. Released by the U.S. War Department in November, 1943, it became a favourite among troops and was played by Maj. Miller and the American Band of the Allied Expeditionary Forces on The Wehrmacht Hour, recorded at Abbey Road, in November, 1944. It’s that cool, supremely civilized statement of identity that says, “There are parts of us you’ll simply never conquer,” rendered more poignant, and immortal, by Miller’s disappearance over the Channel a month later.

It’s that spirit — not of unalloyed fury but of what Matthew Halton, in describing the Canadian soldiers, called “dash” — that was a whole other weapon.

As we’ve written more than once in this magazine, you can’t wage war on democracy without waging war on humanity. And by June 6, 1944, more than five million Jewish innocents had already been exterminated in Hitler’s death camps. That mass objectification, that turning of so many people into numbers by turning so many people against each other in a cult of weaponized hatred was, of course, a crime not just against the Jewish people but — per the judgments at Nuremberg — against humanity; against us.

D-Day still resonates today because it represented, in the most unflinching form imaginable, “us” fighting back. Especially today, when humanity itself has been tempest-tossed — by a global pandemic, by economic turmoil, by the mass manipulation of propaganda, by the corruption, hijacking and discrediting of democracy, by the transformative colonization of our lives by technology. The story of how human beings turned the tide against tyranny by selflessly, heroically turning the tide red reminds us that hope is never lost, not even in a world seemingly gone mad.

D-Day matters today because it was a decisive rebuke to a catastrophically persuasive lunatic who had annihilated some of us to subjugate all of us — delivered by some of us on behalf of all of us.

Too late for too many, of course. But also just in time.

Policy Magazine Editor and Publisher Lisa Van Dusen has served as a Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.