The Flawed, Formidable Nancy Reagan

By Karen Tumulty

Simon & Schuster/April 2021

Review by Arlene Perly Rae

May 6, 2021

Traditional guidance recommended to the mother of the groom: Show up. Shut up. Wear beige. It neatly, (though perhaps not as succinctly), echoes counsel commonly given to the female spouses of politicians.

To “charm and disarm”, soften and prettify — usually through persistent references to children and family — is encouraged as a political wife’s asset mission. Adherence to this formula is meant to balance and humanize the persona of the typical, ambitious political guy.

Strategists insist that this conventional, submissive behaviour boosts the perception of a politician, increasing his appeal to potential voters. Or so the theory goes.

That advice did not register with Nancy Reagan. She was not cut from that predictable cloth. Besides, her spouse was tremendously popular, known as a regular guy — folksy and engaging. And Nancy, well, she just wasn’t.

Nancy is remembered for “the gaze”; her adoring, unwavering stare at her beloved “Ronnie”, otherwise known as governor of California (1967-1975) and 40th President of the United States (1981-1989), Ronald Wilson Reagan.

But the gaze was for the public. Her private behaviour as wife, mother and partner was very much at odds with the stereotypical political wife model of her era.

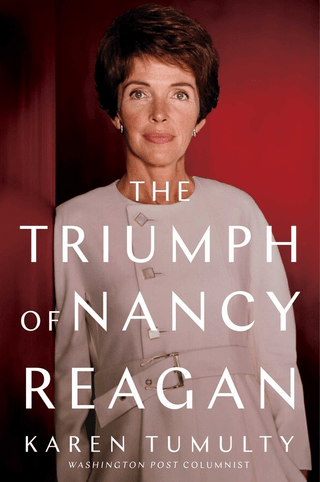

According to biographer Karen Tumulty — a longtime Washington Post and Los Angeles Times reporter and columnist — in her thoroughly researched, comprehensive biography, The Triumph of Nancy Reagan, this particular former First Lady, though small in stature, was a commanding and significant influence in Washington.

Tumulty expands on the longstanding conventional wisdom that Nancy was smart, politically canny and held a great many opinions she was not hesitant to share. She meddled constantly in Ronald Reagan’s political campaigns and, moreover, actively intervened and imposed her will throughout his government. Many were afraid of her. Senior staff ignored her at their peril, with White House Chief of Staff Don Regan’s departure the most notorious cautionary tale.

Nancy put pressure on hirings and (more often) firings. President Reagan himself was apparently far too nice to personally ever let anyone go. Sticky decisions like that, he delegated.

She ruled her husband’s schedule, including the often bizarrely chosen timing of all travel and announcements. After the assassination attempt that nearly killed him on March 30, 1981 three months into his first term, and until years later, Nancy decreed the president’s movements based on the advice of California astrologer Joan Quigley, whom she consulted frequently by phone.

Afraid for her husband’s stamina, Nancy limited access and monitored appearances. She selected (often astutely) her preferred speechwriters and insisted that the president only be in the public eye when well-rested and at his best. Her instincts — more astute regarding him than herself — while not always appreciated, were often on the right track.

For Nancy, image, not substance, was paramount. If anything went wrong, as inevitably things occasionally did, it was always someone else’s fault, never the president’s or her own. The extent of her influence, Tumulty effectively explains, cannot be ignored or underestimated.

It is fascinating how besotted the Reagans were with one another. The president could not imagine his wife doing or saying anything amiss. Throughout their long marriage, they were romantic, sentimental, publicly demonstrative and hated to be apart. They were so in love, according to Tumulty, there was little love left for their children. They were terrible parents; Ronald, for the most part, was remote and disinterested, Nancy was difficult and provocatively judgmental.

As I read Tumulty’s re-telling and remembered Diana’s show-stopping dance with John Travolta, twirling to a medley from Saturday Night Fever, I recalled that only a few years later, I bemusedly watched my husband, Bob, starry-eyed at his own good fortune, dreamily dancing with Diana at a ball in Toronto.

For years, Nancy made headlines for all the wrong reasons. She was extravagant, spending far too much on clothing and decorating. Memorably, she was pilloried in the media for ordering a huge set of expensive China for the White House during a recession, though it was privately funded. While the president continued to be seen as a man of the people, Nancy was constantly criticized as being out of touch with everyday Americans.

So, why Nancy, and why now?

As Tumulty reveals, Nancy Davis Reagan — from her childhood insecurities, less-than-stellar (mostly orchestrated by her mother) acting career, personal struggles with anxiety and lifelong dependence on sleeping pills — is, it turns out, a far more complex and interesting a person than I, and perhaps others, might ever have imagined.

Also timely is the debate over what constitutes a Republican. Thirty years ago, it was less complicated. Fiercely anticommunist and doggedly opposed to big government, President Reagan proudly declared that “Government is not the solution to our problem. Government is the problem”.

He truly believed (despite their gay friends), that sexual orientation was a lifestyle choice. Nancy, on this issue, was more accepting. Reagan’s traditional Republicanism was grounded in the simplistic, popular, conservative mantra: lower taxes, personal accountability and freedom with a capital F. Today’s debate to define the Party pits Trump, bombast and believers in the cult of personality against proponents of the historic right-wing Republican blueprint.

Perhaps Nancy was ahead of her time, as she cared little about policy or the truth and all about perception. Hollywood studios, Tumulty reminds us, “lubricated by fantasy, manufactured tidbits” about their contracted stars. The term “alternative facts” had not yet been invented but Nancy Reagan would have embraced the concept with gusto.

Her focus, following the Hollywood model, was entirely on the public persona of her husband. She concocted or denied stories as situations warranted. Her own brother, Dick, commented that he often “remembered events differently”.

Feminists called Nancy Reagan “a fifties throwback”. More empathetic writers at the time insisted her strong personality was refreshingly modern.

She once gamely tried to improve her image by dressing in cheap clothing and singing a parody of Second Hand Rose to her (astonished) husband, assembled press and dignitaries at the annual Gridiron Club dinner. She also took up a cause, the “Just Say No” to drugs campaign. Both maneuvres were successful, despite her dependence on prescriptions and various drug issues involving the Reagan children.

Nancy fiercely controlled the Reagans’ social life, and knew the value of a strategic seating plan (a useful piece of trivia for diplomats and their spouses: hostess and hostile derive from the same root: hostis, the Latin for enemy). The Reagan’s parties and state dinners were lavish, legendary and dotted with movie stars. In 1985, they hosted a White House dinner for Prince Charles and Princess Diana, then at the height of her celebrity. Despite objections, Nancy deliberately excluded Vice President George Bush and his wife, Barbara, from the invitation list. The successive First Ladies famously did not get along.

As I read Tumulty’s re-telling and remembered Diana’s show-stopping dance with John Travolta, twirling to a medley from Saturday Night Fever, I recalled that only a few years later, I bemusedly watched my husband, Bob, starry-eyed at his own good fortune, dreamily dancing with Diana at a ball in Toronto.

Tumulty effectively summarizes the main challenges of the Reagan administration, including the AIDS epidemic and the Iran Contra crisis, adding to the history, the extent and nature of Nancy’s involvement. She empathetically describes the couple’s very public transparency as each battled cancer, and later, how consistently and devotedly Nancy cared for the former president through his dementia. Perhaps it is the Nancy of these later years that best encapsulates the triumph of Nancy Reagan.

My only quibble is that Tumulty, like Nancy, refers to the former president as “Ronnie” throughout. It felt too familiar and, frankly, annoying. I found myself substituting “the president” or “Reagan” in my head a lot of the time.

The Triumph of Nancy Reagan is a stimulating and fascinating book, written by a woman who effortlessly combines detailed research with a talent for very readable prose. Tumulty’s triumph is that she convincingly reveals a dynamic, complicated and — if not always likeable — formidable woman.

Arlene Perly Rae is a writer living in New York, where she gazes unwaveringly at her husband, Canadian Ambassador to the United Nations Bob Rae.