The Fiscal Update: Do Modest Deficits Matter?

As pivotal days in the annual policy calendar of the nation’s capital go, the finance minister’s fall fiscal update—officially the Update of Economic and Fiscal Projections—has gradually become almost as big as budget day. In an interconnected world that changes faster than at any previous point in human history, fiscal policy must incorporate a rapid response capacity and a global perspective.

Kevin Page and (Matt) Jian Shi

Finance Minister Bill Morneau tabled his fourth economic and fiscal update in the House of Commons last November 21. As far as updates go, this Fall Economic Statement 2018 (FES) is strategically important for the government, and possibly for the future fiscal health of the country.

We are now in an election year. The Liberal government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau will build its 2019 campaign case around the policy record and economic outlook presented in the update.

The economic picture of the country has shifted. The Canadian economy is much stronger now than it was in 2015 when the government took office and laid out its fiscal strategy. Interest rates are rising, reflecting changes to monetary policy. Budgetary deficits and rising interest rates are a toxic mix for public finance. If the government was going to adjust its fiscal strategy, the 2018 update would have been an opportune time.

In this context, the finance minister and the federal government laid their cards on the table. The economy is strong. Using the average private sector forecast, they plan on the economy remaining strong through the 2019 election and beyond. With respect to budgetary policy, it will be business as usual. As long as deficits and debt remain modest, they will continue to spend to address policy priorities. In the November statement, this meant responding to business concerns about the loss of a corporate tax advantage with the United States.

There is a lot at stake with the outlook and strategy. Get the planning outlook right, and the government will look smart, and confidence will build in the government’s plan. Get the outlook wrong, and the government could be forced to make ad hoc adjustments and policy reversals, undermining confidence in the government. Remember the experience of Prime Minister Stephen Harper and the Conservative government in the fall of 2008 when the prime minister was forced to shut down a minority Parliament soon after an election? Confidence can be very fickle.

The economic record of the Liberal government is strong. In the fall of 2015, when the government took power, the economy was weak––real GDP was flat, the unemployment rate stood at 7 per cent, and employment was up about 130 thousand jobs over the previous year. In November of 2018, the Finance Minister could report that real GDP growth was up 2.5 per cent, the unemployment rate was down to 5.6 per cent, the lowest in 40 years and employment growth was up more than 200,000 over the previous year. This is a politically winning economic record. While budgetary deficits are higher than predicted, they are modest. In a political environment, many Canadians will take a strong economy and modest deficits rather than the opposite.

The economic outlook underpinning the government’s plan is a Goldilocks scenario. It is effectively an unchanged outlook from Budget 2018 which was tabled February 27, 2018. Growth remains at potential throughout the medium term. There is little movement in many headline numbers. It is stable as far as the eye can see with respect to inflation, unemployment, and exchange rates. Interest rates rise ever so slightly so as not to shock a household sector loaded with debt.

Morneau can safely say that this is the average private sector outlook. Blame them if reality bites. On the other hand, there is not much in the analysis to suggest how the government’s fiscal policy and plan would handle unanticipated events, beyond a small contingency reserve of $3 billion a year (roughly equivalent to the new measures introduced in the Update to help businesses). This is the usual rule-of-thumb buffer for downside changes to GDP and interest rates but some analysis of what more and less optimistic forecasters are saying would have been helpful.

In our view, the federal government’s plan and potential political fortunes are vulnerable to an unanticipated negative economic event. The current expansion is 10 years old. While it is true that expansions don’t die of old age, many observers of economic and political news express growing anxiety about the possibility of a loss of business and consumer confidence stemming from a trade war between the US and its major trading partners; the build-up of global corporate debt (as highlighted by the IMF in its recent Global Financial Stability Report); and a mismatch between monetary and fiscal policy where rising interest rates coincide with the end of fiscal stimulus. Some of these concerns have been reflected in recent volatile swings in equity markets. In the next recession, Canada is particularly exposed due to high household debt. The analysis underpinning the November update was largely based on “sunny ways”. There is no analysis of negative scenarios. There is no precautionary philosophy or principles.

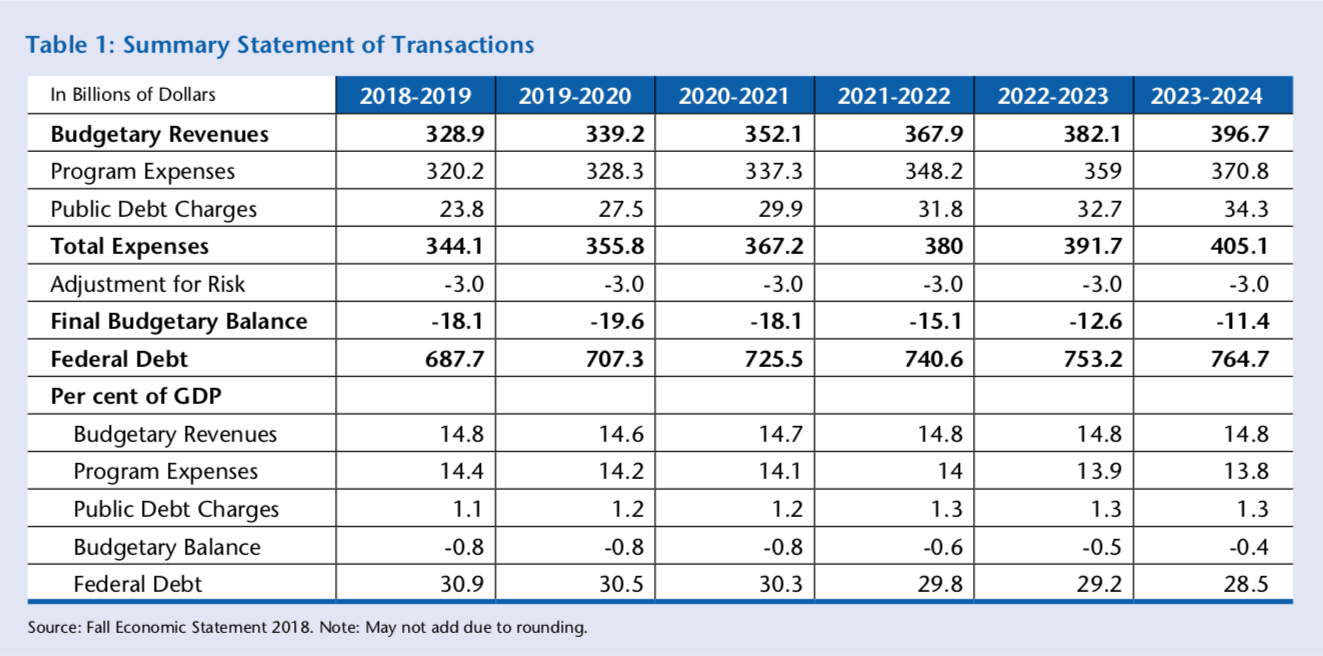

Table 1 provides a balance sheet perspective of the fiscal plan presented in the 2018 FES. Federal budgetary deficits hover in the $18 to $20 billion range over the next few years before they begin their gradual descent. The deficits do not go away despite the assumptions of a strong economic outlook. In this planning environment, the debt increases by about $80 billion over the next five years (about 11 per cent).

In 2019-20, a projected federal deficit of $19.6 billion represents less than 1 per cent of GDP. A projected federal debt of $707 billion represents 30.5 per cent of GDP. The deficit and debt numbers are modest compared to other Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries and do decline over the planning period. A declining federal debt-to-GDP ratio is effectively the only fiscal anchor of the government. Again, in the context of a strong planning outlook, the government is betting that Canadians accept the trade-off of higher debt––of which the increased interest costs will be faced by future generations––as a necessary and convenient trade-off for good economic numbers today.

In many ways, the fall statement was more of a mini budget. It weighed in at a hefty 155 pages. There were some 20 measures that resulted in adjustments to the fiscal planning framework totaling about $17.6 billion over six years, only slightly less than the $21.5 billion in new measures announced in Budget 2018. In the current fiscal environment, it is accurate to say that all of these measures are deficit-financed.

Where the government found the fiscal room for the $17.6 billion is a little bit of a mystery for the bean counters. The economy, as defined by nominal GDP, is relatively unchanged, yet it is assumed in the FES that budgetary revenues will increase close to $25 billion over the next five years. For some observers, this looks like hocus pocus, abracadabra, voilà! We have a source of funds for a mini budget with no pain (except for the next generation of taxpayers).

Embedded in the fiscal planning framework, as well, is an additional $9.5 billion of “non-announced measures”. While it is not unusual in the work of governments to set aside some monies for provisions against contingencies, this is a rather large number and looks to contain future policy measures. Why not wait to adjust the fiscal planning framework when these measures are announced, so parliamentarians are better placed to judge the merits of a proposal in a broader fiscal context?

Virtually all the measures proposed in the fall statement were focused on the business sector. The signature initiative (totaling $14 billion over 6 years) was the immediate expensing for machinery and equipment in the manufacturing and processing of goods, as well as clean energy equipment and their supporting sectors.

Strategically, this was bold policy and a smart political move. One year before a federal election, the government moves to level the playing field on business investment in the wake of significant tax reductions enacted by President Trump and a Republican Congress. The Liberal government can now plan its political campaign for 2019 with some appeasement of the business sector, and can make the claim that Canada, unlike the US, remains largely fiscally sustainable. However, from a citizen perspective, we also need to be reminded that we are deficit financing the corporate sector.

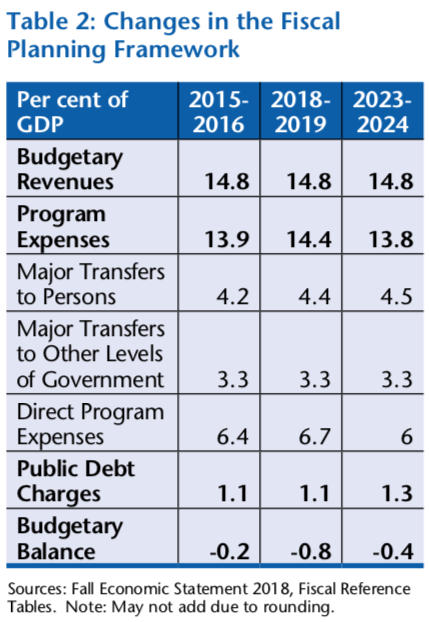

In assessing the fiscal direction of a country, it is often helpful to look at revenues and spending as a share of GDP (actual and projected). These numbers can sometimes separate signals from the noise. Table 2 examines changes in the fiscal planning framework at three junctures: a) 2015-16, when the government took office; b) 2018-19, effectively where we are today; and c) 2023-24, the endpoint of the medium-term planning period.

A few observations worth noting: 1) the increase in the federal deficit over the past few years is related to spending; 2) the planned decrease in the federal deficit over the medium term is related to spending; and 3) revenues as a share of GDP are held constant. (Conservatives may like to argue otherwise.)

This raises a fundamental question. How much confidence can Parliament and Canadians have in the government’s fiscal plan going forward––namely a gradual reduction in modest deficits––if the plan is based on reining in the growth of spending?

Specifically, the plan calls for a significant reduction in the growth of something called direct program spending (i.e.: grants and contributions for programs like infrastructure and research and development, as well as operational spending including wages, salaries, and benefits for public servants.)

However, this component has contributed the most to the higher deficit in the past few years and, implicitly, is key to better economic outcomes for Canadians. It is also noted that this component of planned spending is the least transparent from a planning perspective. We simply do not have the details to assess the strength of this spending plan.

Economists like to deconstruct budgetary balances to better understand the role of the economy in the fiscal framework. A stronger (weaker) economy is more apt to promote stronger (weaker) revenue growth and weaker (stronger) spending growth, particularly for programs like employment insurance. One of the cardinal public finance rules to maintaining healthy levels of debt is to encourage governments to use counter-cyclical fiscal policies: provide support for a weaker economy, and withdraw that support when the economy is strong. The latter is sometimes referred to as taking the punch bowl away from the party.

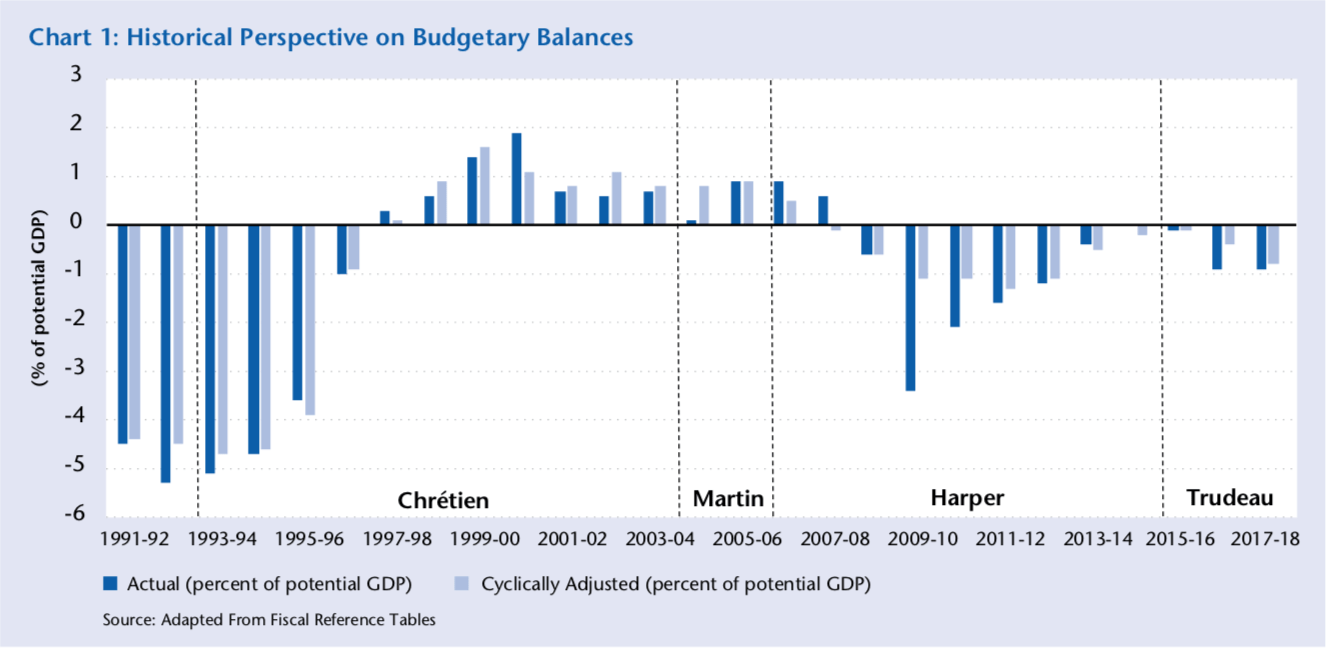

Chart 1 provides the federal Department of Finance numbers for the budgetary balance in actual (as reported) and cyclically adjusted bases. The Finance Canada analysis indicates the current budgetary deficits are virtually 100 per cent structural in nature. They will not go away without specific measures to raise taxes or restrict spending.

In historic terms, Chart 1 illustrates how the Liberal governments under Prime Ministers Chrétien and Martin broke the backs of structural (cyclically adjusted) deficits that existed throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. The Conservative government under Prime Minister Harper and the current government under Prime Minister Trudeau have brought the structural deficits back.

The structural deficits that have existed since 2007-08 are modest in historical terms. It can also be argued that the structural deficits run by Prime Minister Harper in the wake of the 2008-09 global financial crisis were fiscally prudent. They helped stabilize a weak and unstable economy. It is more difficult to argue that the modest structural deficits run by Prime Minister Trudeau are fiscally prudent unless you are convinced that the government’s policy agenda will strengthen the potential GDP of Canada in a way that results in younger generations not minding paying a higher public debt interest as they get older and have less fiscal room to address the challenges of their times.

The last time we had an economy as strong as the current one was in the mid- 2000s. Under Prime Ministers Martin and Harper, the federal government was generating budgetary surpluses larger than $10 billion. This compares to budgetary deficits forecast by Finance Minister Morneau of just under $20 billion. Notwithstanding the modest size of the federal deficit, fiscal policy is very different this time around.

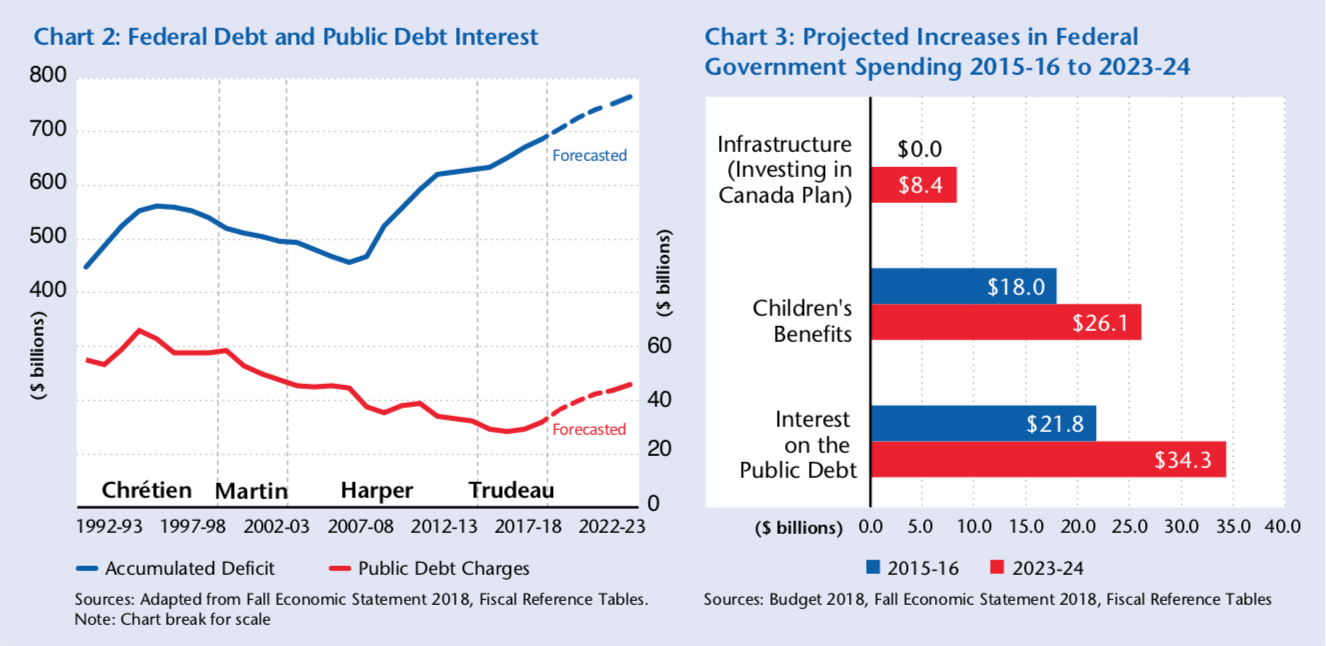

Chart 2 provides some historical and planned context around federal debt and public debt interest payments. In nominal terms, it is clear that there has been a substantial increase in the stock of debt since the mid 2000s, and the slope of the upward trend remains relatively steep. Interest on the cost of debt has only recently hit an inflection point and is projected to increase at a fast rate in the years ahead, reflecting both the build-up in the stock of debt and the impact of rising interest rates.

Chart 2 provides some historical and planned context around federal debt and public debt interest payments. In nominal terms, it is clear that there has been a substantial increase in the stock of debt since the mid 2000s, and the slope of the upward trend remains relatively steep. Interest on the cost of debt has only recently hit an inflection point and is projected to increase at a fast rate in the years ahead, reflecting both the build-up in the stock of debt and the impact of rising interest rates.

Governments will naturally want parliamentarians and citizens to focus on signature policy initiatives. Chart 3 illustrates the net annual increases in spending on child benefits and infrastructure. These are substantial changes which, the government argues (likely with merit), will help strengthen the fortunes of the middle class. Chart 3 also illustrates that the visa bill of the government will grow by a larger amount. There is a cost to modest deficits.

Kevin Page, former Parliamentary Budget Officer, is President and CEO of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at University of Ottawa. (Matt) Jian Shi is an Economics student at the University of Ottawa.