The Evolution of Arrival

It’s hard to think of anyone who knows more about Canada than the man who, every night for nearly 30 years, told us what was happening here and around the world. Peter Mansbridge asked the questions Canadians couldn’t and masterfully filled the gaps during royal visits, national tragedies and, perhaps most memorably, every Remembrance Day, when his appreciation of both history and sacrifice was unabashed. The country, and its newcomers, have changed since he arrived in what was then still an ‘outpost of British civility.’

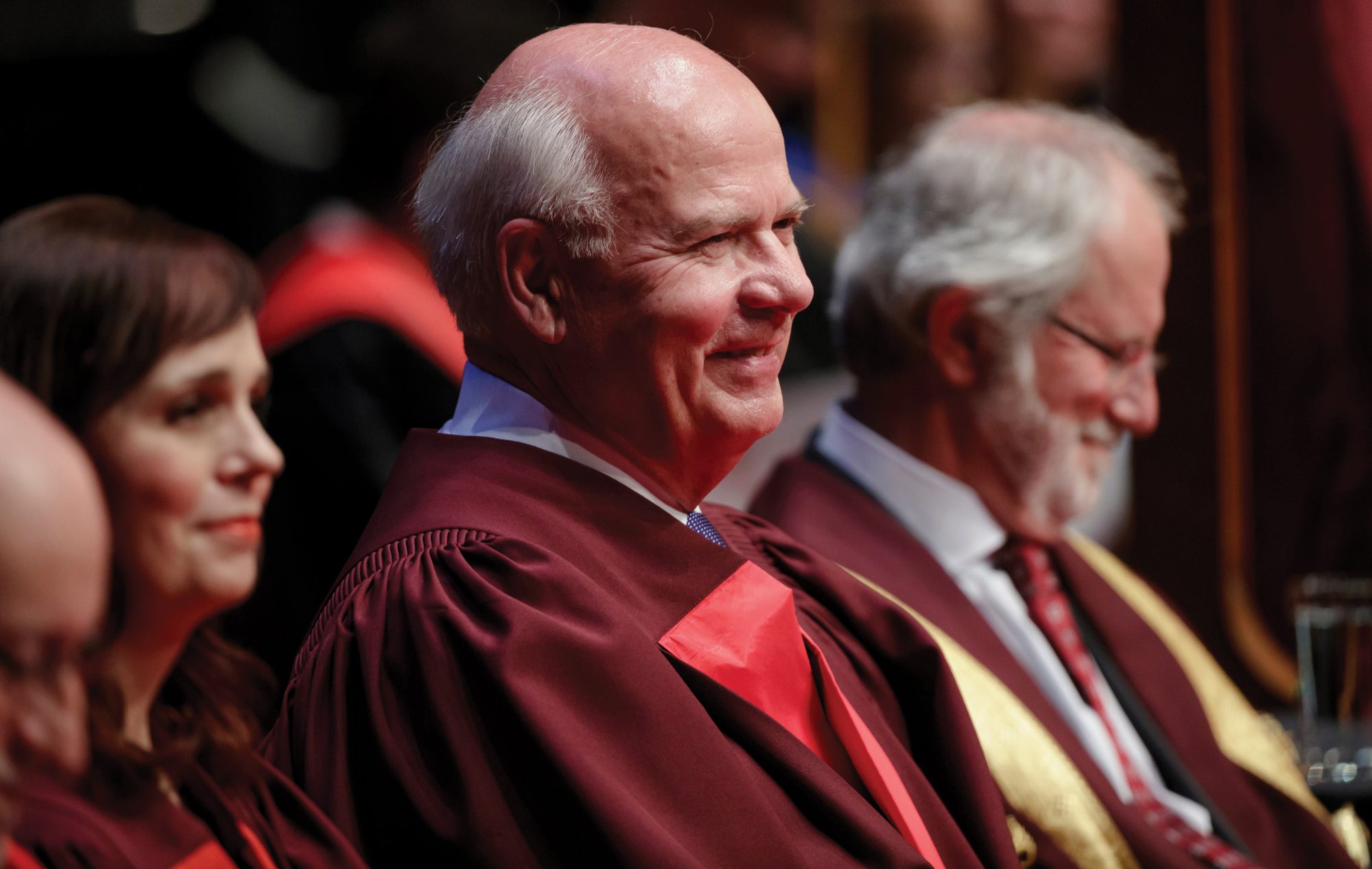

Peter Mansbridge

The morning broke cold and overcast in Quebec City on April 23rd, 1954 as the SS Samaria of the Cunard Shipping Line slid into port. It had left the United Kingdom only a week earlier. The old one-stacker had started life as a cruise ship in the twenties before being converted into a troop ship shuttling young men across the North Atlantic during the war. Now, less than a decade after the Second World War had ended, it was living out its last days bringing immigrants on the voyage to what many still called the “new world”. Anxious to step on land, an excited 5-year-old, braving the Canadian cold in gray shorts, gray socks and a sensible English knit sweater, led his family down the gangway to a group of waiting Canadian immigration officials. It would be, for him, day one of a great journey.

It was my first day in Canada.

My father, a decorated veteran of the Royal Air Force, had been offered a job in the Canadian public service. Along with my mother, they were anxious to find a safe haven to raise their young family. They’d been through the great conflict in Europe, and followed that with four years of tense times for British government officials when we lived in Malaya. We loved our new country and, as kids, my sister and I settled in fast. So fast, in fact, that even still clinging to our accents, we were chosen, just a few years after coming off the Samaria, to portray two typical Canadian students in a film for the National Film Board, “A Visit to the Parliament Buildings”. It even included a scene with the new prime minister, John Diefenbaker. Twenty years later I showed “The Chief” a photo of that 1958 moment when I was a parliamentary correspondent for the CBC in Ottawa—amazingly, he remembered every detail of the encounter. He signed it for me and it remains one of my prized possessions to this day.

The country has changed a lot in the sixty-five years since I walked down that gangway not much more than a toddler, and I’ve witnessed Canada change, and grow, and mature.

Part of the change has been about immigration, not an issue that flatters our early history. Until the 1950s we were known more for erecting walls than laying out the welcome mat. Just ask the Chinese, or the Japanese, or the East Indians who tried to come to Canada at the dawn of the 20th century, or Jewish immigrants desperate to find a home in the 1930s. Or so many other examples that leave many of us embarrassed still.

But two world wars and the fear that other conflicts could start—that human slaughter could occur again—changed things. Fairly quickly, Canadians started to gain the reputation that, at least when a crisis was at hand, our shores welcomed those most threatened.

When the Hungarian uprising against the Soviets was crushed in 1956, hundreds of thousands of Hungarians fled across the border into Austria. Canada began an airlift, and 200 flights brought more than 37,000 Hungarians across the Atlantic. In 1968, the Prague Spring ended in similar fashion when the tanks moved into the cobblestone streets of the Czech capital. Another exodus, and this time Canada took in almost eleven thousand.

Our immigration records show that in the early 1970s, the United States was the largest source country for immigration. Why? It appears those trying to avoid the draft for Vietnam boosted the numbers. Estimates range as high as 40,000. In 1972, Idi Amin’s butchery and forced expulsion of Ugandan Asians led Canada to organize another airlift and secure citizenship for almost 7,000 people.

In the summer of 1979, I found myself in a refugee camp in Hong Kong watching a lone Canadian immigration officer make decisions about which of the so-called Vietnamese “boat people” would be allowed to come to Canada. I’ve covered thousands of stories and interviewed tens of thousands of people since, but I’ve never forgotten the details of that moment. His name was Scott Mullen and he was barely out of university but there he was, sitting at a makeshift table among thousands of ethnic Chinese who’d risked their lives and given up everything they owned to pay the exorbitant fees ship captains were charging to help get them out of Vietnam.

Mullen had to decide, in an instant, who got in to Canada and who didn’t. I was in awe of the young man’s determination to do the right thing for his country, and do the right thing for those desperate people who simply wanted to find a safe home for their families. Over the next year, Canada accepted close to one hundred thousand. Compare Scott Mullen’s resources to what we witnessed as Canada swooped into the refugee camps in Lebanon to decide who we’d accept from the brutal and ugly civil war in Syria. Immigration officers, armed forces personnel, the RCMP. A full court press determined to ensure there were no terrorists hidden amongst the tens of thousands of refugees Canada would eventually welcome. What a difference thirty-plus years make.

What about the difference 65 years makes? Let’s think about that for a minute. When the Samaria docked in 1954, the faces were white, the passports were mostly British. It’s who we were then. It’s how we defined ourselves. The statistics don’t lie: we were, as the University of Toronto’s Harold Roper told the Toronto Star in 2013, a country that saw itself as an “Anglo-British outpost of British civility”.

So, what are we now? Have we really changed?

If you find yourself in the crowd at a Toronto Raptors home game, the answer is a very firm “yes” on the change question. You are surrounded by the new faces of Canada, a wonderful mix of everything a true mosaic can produce …. no one would call it an “Anglo-British outpost”.

But outside of that venue, trying to describe, who we are as a nation in 2019 is a much tougher question to answer. Immigration has always been an issue for Canadians, and while time has changed the equation a bit, it remains a contentious issue.

Why? What does it expose about us? Why do we struggle with it?

Is it racism? Is it fear? Is it economics?

Is it a little bit of all of the above?

It’s an easy bet that when Canadians head to the polls this fall, the big issue for some will still be immigration—how many new immigrants should be let in, from where, and with what impact. It remains a defining issue, perhaps the defining issue any country can ask itself—

who are we?

When a five-year-old from Syria steps off the plane for his or her first day in Canada, is she or he as excited as I was all those years ago? Her parents are dealing with a lot more than my parents were—for them, the emotional and financial pressures must be, at times, overwhelming. Are we as Canadians as welcoming to that five-year-old and her family as the country was to me? I’m not sure.

There are real undercurrents out there across the land, that when exposed, call into question what we as individuals believe, and what we want and expect from our country.

It’s unfinished business and it’s time we dealt with it.

Peter Mansbridge is the former anchor and chief correspondent of CBC’s The National. He is a Distinguished Fellow at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the University of Toronto.After 30 years in the anchor’s chair, he is now producing documentaries and appearing as a public speaker.