The Enduring Meaning of Treason

The propaganda proxies of the war on democracy avoid the word treason for a reason. Its meaning hasn’t changed.

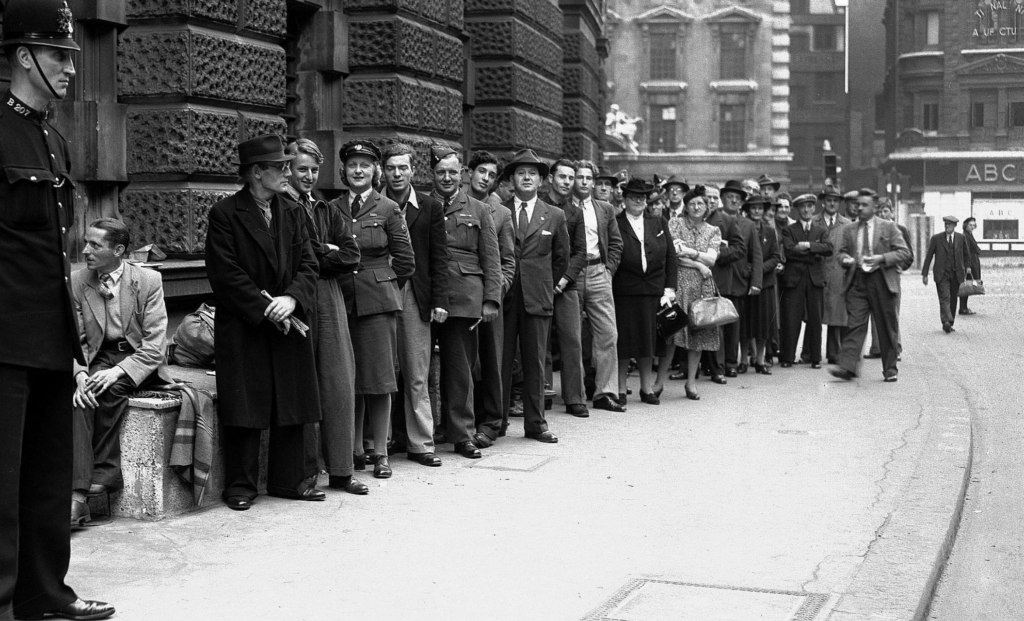

A lineup outside the trial of British Nazi radio propagandist Lord Haw Haw in September, 1945, covered by Rebecca West in The Meaning of Treason/AP

Lisa Van Dusen

December 20, 2021

The definition of treason, per Merriam Webster, is “The crime of trying to overthrow your country’s government or of helping your country’s enemies during war.”

The definition of treason per the United States Criminal Code, Chapter 115, Section 2381 is as follows: “Whoever, owing allegiance to the United States, levies war against them or adheres to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort within the United States or elsewhere, is guilty of treason and shall suffer death, or shall be imprisoned not less than five years and fined under this title but not less than $10,000; and shall be incapable of holding any office under the United States.”

The definition of treason in Canada, per the multiple provisions of Section 46 of the Criminal Code, distinguishes between high treason and the sub-category of treason, covering the same principles of levying war against the government, violence, conspiracy and other nuances of this particular crime of character, with the addition of specific acts of force or restraint against “Her Majesty”.

The fundamental concept of treason has not changed since Rebecca West authored her explorations of the crime in The Meaning of Treason (1947), based on her coverage for the New Yorker of the British treason trials of WWII pro-Nazi radio propagandist William Joyce (aka Lord Haw Haw) and Nazi collaborator John Amery, among others, and her expanded The New Meaning of Treason (1964), updated to include the Cold War variation, with the Cambridge spy scandals. “I cannot think that espionage can be recommended as a technique for building an impressive civilization,” West said. “It’s a lout’s game.” Espionage has changed significantly since the wireless covert innovations of the fourth industrial revolution. Treason has not.

When a government is serving its citizens, as is required by un-corrupted democracies as an element of political survival, treason against that government is treason against the people. When a government ceases to serve its citizens and instead serves the interests of a power cabal or tyrant, as happens in corruption-captured democracies, authoritarian and totalitarian regimes, peaceful actions against such a government — as on the part of Soviet dissidents, Belarusian protestors or Myanmar democracy activists — are acts of resistance.

These lines can be opportunistically blurred when a major power centre in a government — say, the military or the intelligence community — treasonously turns against its elected representatives and therefore its fellow citizens, with the help of collaborators who may console themselves that they’re following orders from government agencies, but who are actually committing treason because they’re providing aid and comfort as proxies, pawns or puppets to interests bent on overthrowing democracy. In other words, simply because someone has a government title, that doesn’t mean doing their bidding isn’t treason.

The notorious defence of “following orders” — also known as the Nuremberg defence — failed to save the necks of the Nazis sentenced to death in the Nuremberg Trials for crimes against peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity, essentially because their government had become an enemy of not only its own people but of humanity.

Espionage has changed significantly since the wireless covert innovations of the fourth industrial revolution. Treason has not.

In today’s context, the question of treason, its applications and permutations, has arisen most recently around events unfolding in the United States, where certain elements of the government have turned against their fellow citizens by turning against democracy, in many cases by flagrantly betraying their oaths of office. For public servants including in Congress, the White House, judges, political appointees, and so on, that oath — with minor adjustments per the office — reads: “I, ___, do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter. So help me God.”

In instances where political actors have agreed to repurpose their power in aid of anti-democracy interests under duress, coercion or on the apparent thinking that a combination of strength-in-numbers and corrupt critical mass makes their choice more pragmatically clever than treasonous, this is not a new rationale and, indeed, has been litigated (see above, “Nuremberg defence”). For reference, the definition of treason in the United States Constitution, Article III, Section 3 is: “Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying war against them, or in adhering to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort.”

In the days and weeks following the deadly raid on the US Capitol staged by a mob of out-of-work actors and viral, democracy-degrading content generators last January, China — which President Joe Biden refers to as a competitor of the United States and, in the current undeclared war on democracy being waged both within and beyond America’s borders, is the principal geopolitical antagonist — took aid and comfort from those events, as it does from all headlines portraying operational dysfunction, intractability and chaos in American democracy. “Chinese propaganda videos have gloated over the Jan. 6 assault on the U.S. Capitol and subsequent impeachment proceedings, portraying them as signs of the decline of ‘American-style Democracy,’” per the Washington Post’s reporting in February.

The failure to prosecute the coup plotters of the outgoing Trump administration would only add to that aid and comfort by confirming that the corruption of American democracy is far more widespread than headlines have described.

The fog of war — especially in an age of narrative warfare in which not only is truth the perpetual casualty but lies are weapons of mass destruction — is always used to obscure and obfuscate long-term stakes and moral questions in real time. But no deflection, diversion, proxy propaganda operation or claim that times have changed can alter the definition of what it is to betray your country and your fellow human beings. Some truths are both self-evident and eternal.

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor of Policy Magazine. She was Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.