The Conversation that Led to a Job with Bill Davis, and a Life in Politics

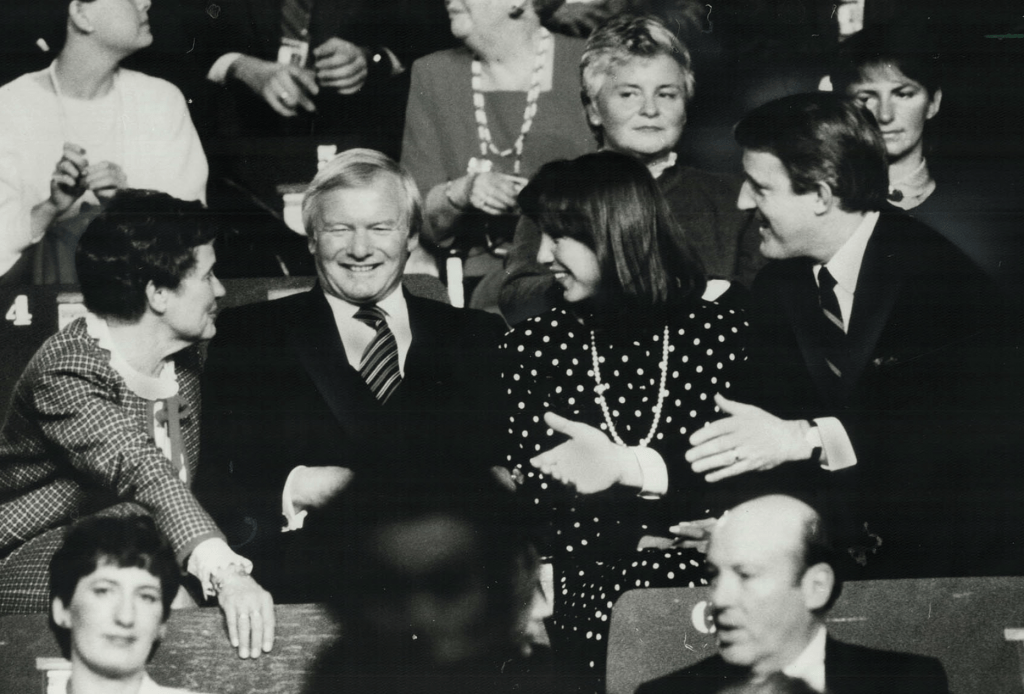

Kathy and Bill Davis with Mila and Brian Mulroney at the 1985 Ontario Progressive Conservative leadership convention/Toronto Star archive via Toronto Public Library

Kathy and Bill Davis with Mila and Brian Mulroney at the 1985 Ontario Progressive Conservative leadership convention/Toronto Star archive via Toronto Public Library

John Laschinger

August 9, 2021

“Would you like to meet the Premier of Ontario tomorrow?”

It was August of 1971, and I happened to bump into John Thompson, my former roommate from University of Western Ontario Business School, on a downtown Toronto street. He told me that he was helping to organize a meeting for Bill Davis, who had succeeded John Robarts as premier that March, and was looking for young professionals to volunteer in the upcoming provincial election. Twenty-four hours later I was a member of what became the legendary Big Blue Machine, committed to helping Premier Davis win the election that was later called for October 21, 1971.

I remember my first impressions of Bill Davis that day as being quiet and shy and having difficulty asking a group of strangers to help him. It was an early glimpse of the paradox of a man who chose a life in the public eye despite being a natural introvert — and never lost a single election.

While the Big Blue Machine — which pioneered many of the polling, communications, advertising and fundraising strategies and practices that became the standard of modern election campaigns across North America — at various points included Norman Atkins, Hugh Segal, John Tory, Allan Gregg, Paul Curley and other political and policy strategists, I was then part of the tour group of advance men whose job it was to coordinate and execute the travel plans of the premier during the election.

Advance men (mostly men back then — now also advance women) literally form an advance party to plot out where the candidate will be going, whom he’ll be meeting in which venue, whether the room is the right size for the crowd expected, whether the media have all the technical, logistical, food, beverage and filing provisions they need and every other contingency that can be reasonably anticipated from the weather to power outages. It’s one of those jobs in politics that sounds less crucial to civilians than it really is because whenever something goes wrong — from a media bus running out of gas to a candidate tumbling off a stage — everyone shakes their head and mumbles, “bad advance”. Our Big Blue Machine recon team called ourselves the Dirty Dozen.

That brief August meeting on a Toronto street changed my life dramatically. I went from a blue suit and white shirt at IBM to a career in politics

Some two months later, Davis had led the Ontario Progressive Conservatives to a majority nine seats larger than the one Robarts had left it with, and I was in Davis’s house in Brampton on election night helping to organize the calls that the premier-elect wanted to make to various winning and losing PC candidates.

Loyalty in politics is a valued but often rarely found commodity. Over the years since those days, I had a number of occasions to talk with or meet with Davis. I was always impressed by his loyalty to whomever the current federal and provincial Conservative or PC party leaders happened to be at the time. He was a true party man.

That brief August meeting on a Toronto street changed my life dramatically. I went from a blue suit and white shirt at IBM to a career in politics, eventually as national director of the PC Party, later as executive director of the Ontario PC Party and ultimately managing or advising 54 campaigns over 50 years. During that time, I have met many fine men and women. But none has been classier than Bill Davis. He treated friends and political opponents the same. When people today yearn for a return to a form of more civilized politics with less vitriol and venom, they often think of Bill Davis.

My thanks and thoughts are with Kathy Davis and her family. They shared a wonderful man with the people of Ontario and Canada.

John Laschinger is a veteran political organizer of election campaigns and party leadership bids for a variety of candidates. He is the author of two books, “Leaders and Lesser Mortals” and “Campaign Confessions: Tales from the War Rooms of Politics”. He lives in Toronto.