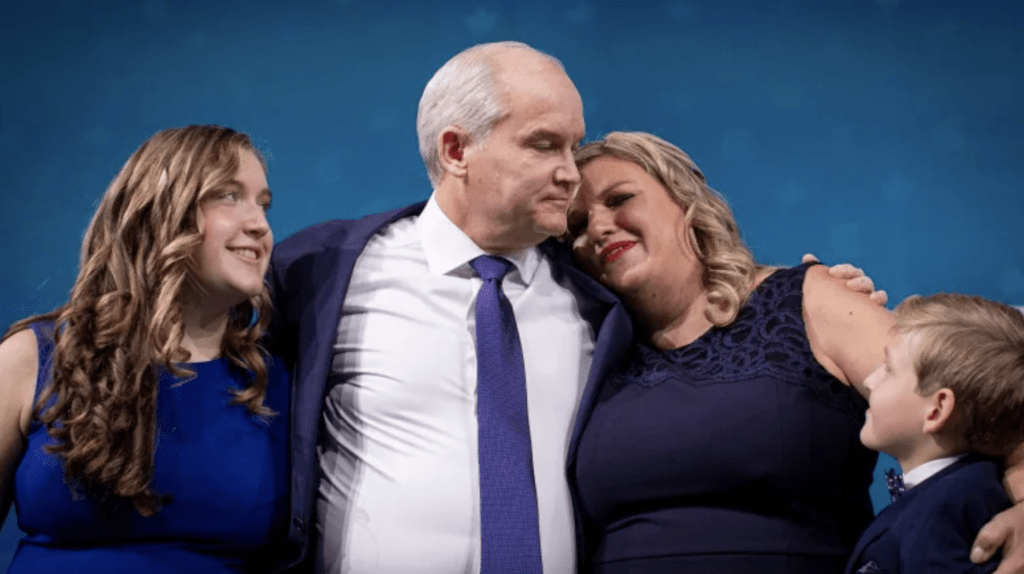

The Conundrum of Erin O’Toole

CBC.ca

Lisa Van Dusen

September 27, 2021

In the post-election speculation about Erin O’Toole’s prospects as leader of the Conservative Party, the question has been asked, “Should O’Toole shift the party back toward the right?”

The premise of the question — that Erin O’Toole is a guy who can take the Conservative Party of Canada in any direction he likes and that it will cost nothing in either personal credibility or electoral viability — is an odd one, especially given that Canadians just litigated it on September 20th.

Absent the clarifying benefits of the fullness of time to reveal the degree to which Erin O’Toole’s campaign trajectory reflected a genuine personal evolution or series of coincidental epiphanies on gun control, climate policy, safe injection sites, unions and other matters of principle, it seems reasonable to assume that he tailored his views to widen his accessible voter pool, the way one might claim to enjoy Ashtanga yoga in a dating site profile to appeal to the nimble.

What the election outcome seems to tell us, given the polling trajectory that preceded it, is that O’Toole’s effort to appeal to any centrists churlish about having a campaign foisted upon them — and possibly willing to take that out on Justin Trudeau by voting Conservative rather than brandishing a “F**K Trudeau” sign or flinging gravel — did two things: First, it alienated his party’s right-wing base by re-animating the abandonment issues that had been largely dormant since the Mulroney era of Progressive Conservatism. Second, it alienated other voters by filling the void of Erin O’Toole’s pre-campaign unfathomability with undesirable focus group word-associations like “opportunist”, “cynical” and “WTF?!”

In the end, by trying to please nobody but his own tacticians, O’Toole pleased nobody, including his own tacticians, by losing. And blaming your tacticians never works, because it only adds “weakness” to the issue you’re blaming them for.

Did O’Toole’s willingness to trade his previously stated beliefs for the chance at a shifty path to victory brand him untrustworthy in a way that now precludes him from credibly shifting himself, much less the Conservative Party, in any direction at all?

Which leaves Erin O’Toole with three problems. First, the short-term viability of his leadership, which may be secured by an early caucus vote — per the provisions of Michael Chong’s Reform Act — before the opposition can organize beyond Bert Chen’s defenestration petition.

Second, what if the aspects of his character revealed during this campaign have left O’Toole with the longer-term problem of a lingering inauthenticity issue or a permanent trust deficit? History has taught us that, while inauthenticity issues and trust deficits often coexist — and, when coexisting in sufficient quantity in a candidate, can repel voters to the point of plausibly making Donald Trump president of the United States — they are not interchangeable. Did O’Toole’s willingness to trade his previously stated beliefs for the chance at a shifty path to victory brand him untrustworthy in a way that now precludes him from credibly shifting himself, much less the Conservative Party, in any direction at all? That’s a trust issue. His real authenticity issue is that any attempt he now makes at authenticity could be undermined by his trust issue.

Third, we live in a borderless, perpetually osmotic political environment and Conservatives everywhere are being identified with the role Republicans in the United States are playing in the corruption and undermining of democracy. That includes taking to new depths the age-old practice of saying one thing to get elected and doing another while in office. When Erin O’Toole ditched his own party platform and previous positions during a close election race, he reminded voters that, in the age of hypertactical politics, there are scarier things than flip-flopping. It wasn’t just the opportunism; it was the suspicion of wholly tactical, insincere opportunism.

The question of whether O’Toole should shift the Conservative Party back to the right when, if he had successfully shifted it anywhere else, the party’s seat count change from the last election might reflect that, may be the wrong one. The more relevant question may be, “What does Erin O’Toole stand for?”

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor of Policy Magazine. She has worked as a Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, an international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington, and a senior writer for Maclean’s magazine.