The Conscience of the Country

Nearly four decades ago, the process of patriating Canada’s constitutional authority from Westminster and formulating a new Charter of Rights and Freedoms catalyzed an exploration and legal entrenchment of Canadian values. As constitutions around the world become targets for populists, Canada’s remains a model for the protection of rights and the codification of democratic governance.

Lori Turnbull

The defining moment in the history of Canada’s written Constitution was arguably its homecoming in 1982 and the concurrent signing into law of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau expressed the following sentiment at the patriation ceremony, attended by Queen Elizabeth II, that saw the power of Westminster to amend Canada’s Constitution Acts transferred to Canadian legislators: “I wish simply that the bringing home of our Constitution marks the end of a long winter, the breaking up of the ice jams, and the beginning of a new spring. What we are celebrating today is not so much the completion of our task, but the renewal of our hope—not so much an ending, but a fresh beginning.”

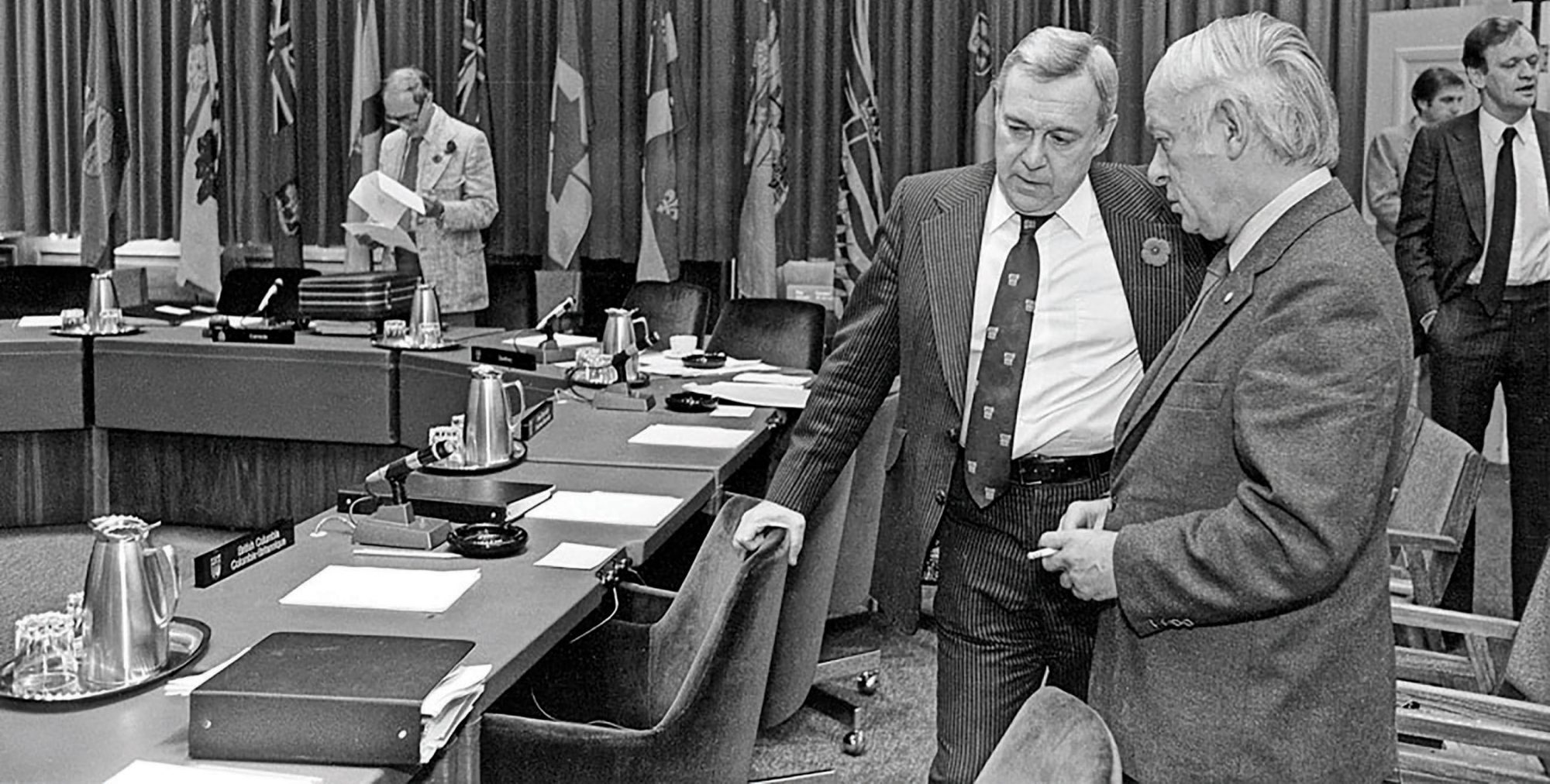

Despite the optimism and positivity of his words, there is no doubt that the prime minister was relieved to draw the constitutional negotiations that had nearly torn the country apart to a close. The provincial premiers, with the exceptions of Bill Davis of Ontario and Richard Hatfield of New Brunswick, resisted Trudeau’s campaign to entrench a new constitution for Canada. Trudeau warned the premiers that he was more than willing to pursue his goal alone and that patriation would happen with or without provincial participation. The Supreme Court confirmed that this was an option.

Quebec Premier René Lévesque was perhaps the most vocal opponent to the prime minister’s plan, framing it as an attempt to centralize the federation and diminish the role and significance of the provinces. In November of 1981, the Prime Minister finally cracked the “gang of eight” by reaching a deal with seven of the eight outlier premiers. Levesque was not invited to these secret meetings and thus the new Constitution went ahead without Quebec’s consent. As the new document was signed in Ottawa, protesters marched in Montreal. The consensus around the new Constitution was broad enough to move forward, but ultimately incomplete.

Canada’s Constitution is unique in its design and evolution in that it has both written and unwritten parts, reflecting the influence of the American and British constitutions respectively. The Constitution Act 1982 and the British North America Act 1867 are the written components; essentially, they lay out the basics of how parliamentary and federal governance operate in Canada.

The earlier document outlines the parameters of executive, legislative, and judicial powers and differentiates between federal and provincial jurisdiction, while the 1982 addition includes the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, an amending formula, and clauses recognizing Aboriginal and treaty rights and the federal-provincial equalization arrangement. The entrenchment of the Charter enhanced the role and significance of the judiciary and turned citizens into rights-bearers and therefore real stakeholders in the Constitution in ways that they had not been before.

The political landscape has changed a lot since 1982. It is the job of a constitution to protect and preserve the institutions and values that define a place but, simultaneously, to adapt and to grow with enduring changes in cultural expectations and attitudes about ideas such as democracy, fairness, social justice, diversity, inclusion, and gender equality. Is Canada’s Constitution successful in meeting this challenge? I would argue that the record is mixed.

The amending formula that was included in the Constitution Act 1982 could be interpreted (positively) as a definitive step in Canada’s gradual emancipation from British colonial rule and, therefore, a measure of our independence as a country. It could also be seen, in retrospect, as a significant barrier to constitutional reform—at least, to formal reform involving changes to the wording of the Constitution. The general amending formula requires that proposed changes have the support not only of Parliament but also of seven of ten provinces representing at least 50 per cent of the population of the country. Some constitutional changes require the unanimous consent of the Senate, House of Commons and legislative assemblies of every province.

Due to deep-seated differences among Canada’s regions, provinces, and territories in terms of their approaches to politics and economics, these thresholds have rarely been met, even when there has been a strong desire for institutional change. As was proven during the Meech Lake process of 1987-1992, the risk that constitutional reform talks will fail is high, which has scared politicians away from meaningful discussions about formal constitutional reform. This stunts our growth as a democracy.

Of course, the amending formula is not the problem; the requirement for intergovernmental consensus on constitutional change is the only just and responsible way to go in a country as large and as diverse as ours. The real problem is the lack of political will to pursue and implement change, even when it is sought by many, and the seeming inability of governments to build a consensus around a preferred course of action. The capacity for consensus building, essential to political leadership, would lessen the political costs of making difficult decisions and would mitigate the risk of failure.

Take Senate reform, for example. Though the traditional Senate model has its supporters, most Canadians are looking for something different. But there is no agreement on what a new Senate should look like, so there is no clear path forward for change.

What has happened instead is that recent prime ministers have pursued Senate reform outside of the formal requirements of the amending formula. Prime Minister Stephen Harper sought to use legislation rather than constitutional reform to introduce term limits for Senators and plebiscites to select candidates for the Senate, only to be told by the Supreme Court that he was not permitted to do through the back door what he could not do through the front. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has taken a different approach: he introduced a non-binding, independent advisory board to make suggestions for appointments based on merit and other criteria. This is a lighter touch and so has flown under the constitutional radar. To put it another way, the new appointments process has no constitutional significance whatsoever and could be undone in a heartbeat.

For its part, Quebec remains outside of the constitutional fold in some ways as efforts to draw it in, including the Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords, have failed. However, in 2006, Harper tabled a motion, which was approved by the House of Commons, that recognized “that the Québécois form a nation within a united Canada.” This was a nod to the distinct society clause that died with Meech Lake and Charlottetown. Though not constitutional in status, it was a meaningful symbolic gesture that signaled the desire of the federal government to repair relations with the province and to recognize Quebec’s special role in Confederation. In connection with this, Dalhousie University’s Jennifer Smith has argued in favour of the propriety of “asymmetrical federalism,” an approach that has been used to make it possible for Quebec to opt out of federal programs in favour of pursuing the province’s own priorities.

Further, bilateral negotiations between the federal government and the provinces allow for more tailor-made policies that are responsive to provincial needs—but, again, this approach allows politicians to avoid the difficult task of consensus building and nation making.

In the absence of the right conditions for formal reform to our governing institutions, our Constitution has grown and evolved in other ways. The courts have been granted a leadership opportunity in moving rights forward in many cases, including same-sex marriage, access to abortion, equal parental benefits, protections for persons with disabilities, and others.

The late Alan Cairns observed that the Charter produced a “vast, qualitatively impressive discourse organized around rights,” through which those claims that meet the threshold to qualify as rights have been recognized not as mere political pursuits, but as non-negotiable entitlements that the state is obliged to honour. The courts’ role in acknowledging rights has been fundamentally important to the Constitution’s evolution and consistency with Canadian values, particularly in cases where the political will for change has been lacking.

Though there has been progress in some areas, Canada’s constitutional maturity is more developed in some areas than others. The reconciliation project, and relations between Canada and Indigenous peoples in general, continue to be wrought with mistrust. Justin Trudeau emphasized Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples as his top priority in the mandate letters he sent to his cabinet ministers on their swearing-in after the 2015 election.

The government followed through on its promise for an inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. Also, the former Department of Indigenous and Northern Affairs has been replaced by two departments: Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, and Indigenous Services Canada. There are positive developments, such as a reduction in the number of on-reserve water advisories, but on more fundamental matters such as the Indigenization of Canada’s Constitution and of institutions of politics and government, there is much to be done. A pre-requisite for progress on reconciliation is the development of a meaningful consensus on what reconciliation really means. This consensus must bridge the space between Indigenous and non-Indigenous persons in Canada to develop a true sense of shared responsibility and common project.

A government’s greatest and most important challenge is to bring people together—not through the suppression of difference in interest or opinion, but through the power of reasoned argument, transformative dialogue, and the reinforcement of a common identity that exists simultaneously with an appreciation of what makes us unique. This was the ultimate challenge that framed constitutional debates in the 1980s, and it is the challenge that remains with us today.

Dr. Lori Turnbull is the Director of the School of Public Administration at Dalhousie University and fellow at the Public Policy Forum.