The Case for a New and Improved Magnitsky Law

Three years after Canada joined the growing list of democracies that have adopted legislation to sanction human rights abusers, updates and improvements are required.

Irwin Cotler and Brandon Silver

September 12, 2020

At a time when democratic norms are under attack elsewhere, Canada has a unique opportunity to set the global standard for human rights practice and policy by reforming and refining Canada’s human rights sanctions framework, which can serve as an example to the world.

Amid a global resurgence of authoritarianism — underpinned by an assault on the rules-based international order — such meaningful measures are as timely as they are necessary, and could catalyze compelling and comprehensive human rights reforms in other countries. Indeed, it would ensure that these efforts are well-grounded and guided by best practices, particularly as allied countries and economies, including Australia, Germany, and even the European Union as a whole, consider the adoption of such sanctions frameworks.

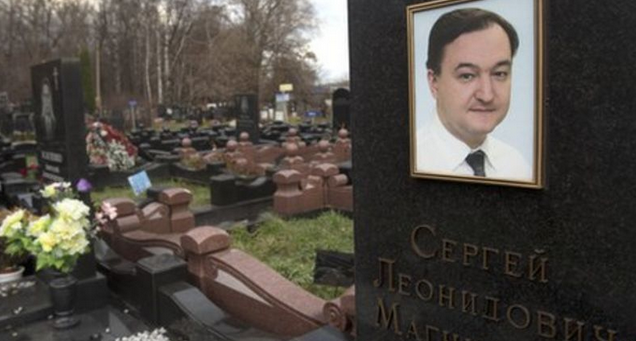

Passed unanimously by the House of Commons in 2017, the Justice for Corrupt Foreign Officials Act — commonly referred to here and in its iterations around the world as the “Magnitsky Law”, so named for Sergei Magnitsky, the Russian whistleblower framed and murdered in 2009 for the crimes he exposed — represents the very best of a bold Canadian human rights foreign policy. In implementing visa bans and asset seizures against individual human rights violators, the Magnitsky Law ensures that despots and dictators cannot enjoy the freedoms in Canada that they deny their compatriots at home. Crucially, it names and shames the perpetrator, shining a deterrent spotlight on their acts of criminality, and telling their victims that they are not forgotten. At the same time, it protects our national sovereignty from the corrosive effects of corrupt foreign capital.

However, as British barrister Amal Clooney put it in her authoritative report on targeted sanctions, Canada’s Magnitsky Law is in many respects “narrower than its UK and US counterparts.” The legislation is limited to individuals — therefore excluding the listing of legal entities, and providing exculpatory immunity to corporations directly involved in violations — and does not allow for the listing of secondary participants in human rights abuses. These omissions should be revisited and revised, lest Canada indulge a culture of impunity for such violations.

As well, given the highly discretionary and opaque nature of the Law’s implementation process, instituting a higher degree of transparency would help build trust and encourage greater civil society participation. Formalizing a role for the public and Parliament in the process would serve this purpose, and would also strengthen standards and expand expertise. For example, US Magnitsky legislation mandates a detailed government response to submissions by legislators, and also encourages submissions from NGOs, which have often anchored and inspired listings. Canadian parliamentary procedure provides some precedent for such legislative oversight practices, as order paper questions have generally engendered substantive governmental responses — in contrast to the evasive non-answers typical of question period or pro forma responses to tabled petitions. A similar mechanism would be especially helpful to sanctions submissions from Parliament, and should therefore be enshrined in Canada’s Magnitsky Law.

Encouragingly, recent developments indicate government interest in building upon Canada’s Magnitsky legislation. The 2018 budget committed $22.2 million dollars over five years toward the strengthening of Canada’s sanctions regimes, and the Foreign Affairs Minister’s mandate letter of December 2019 directs him to develop a “framework to transfer seized assets from those who commit grave human rights abuses to their victims,” which has been affirmed by a commitment to operationalize this directive in the 2020-21 Departmental Plan of Global Affairs Canada.

Initially invoked in Senate Bill S-259 and grounded in the recommendations of the Canadian-led World Refugee Council Call to Action, the transferring of assets would, as sponsoring Senator Ratna Omidvar described, be the logical next step from the status quo of freezing assets — where they remain immobile and without purpose — so that it will “through court order, seize these assets in order to repurpose them back to help the people that have been forced to run for their lives and seek safe haven.”

While Bill S-259 died on the order paper at prorogation, the important idea behind it need not die. In the new session of Parliament, legislation should be proposed to create a judicially monitored mechanism for the transfer of frozen assets to victims, and it should expressly include the capacity for claims from individual victims.

Canada should seek to individually and collectively intervene to proactively support the adoption of global Magnitsky legislation in liberal democracies, providing endorsement of the process, and lending experience and expertise in the development of its substance.

The individual dissidents and human rights defenders who put not only their livelihoods, but their very lives on the line in the defence of fundamental freedoms are particularly deserving of consideration in such a framework for the repurposing of frozen assets. Indeed, it is most often through their submission of evidence — or that of their surviving family members — that the identification and sanctioning of human rights abusers is undertaken. While no amount of money could ever compensate for the loss of loved ones, loss of limbs, or for the years lost in unjust imprisonment, it could at least help them cover some of the heavy costs involved in reclaiming their lives. These individuals who have been devoted to helping the most vulnerable deserve to get the help that they so desperately need — whether psychologists, physiotherapists or other critical services — but that is far too frequently out of reach for them financially. Moreover, there is often a direct pecuniary component to the targeting of these courageous individuals, where their assets are unjustly confiscated by the human rights violators, or where they are subjected to onerous financial penalties or exorbitant bail costs in the case of arbitrary arrest. Therefore, at the very least, they should be permitted to recover the assets that were stolen from them by those listed perpetrators.

The high evidentiary thresholds involved in the listing of human rights abusers necessitate determinate instances of violations rather than generalized descriptions, which means that individual victims linked to the frozen assets are easily identifiable. Further, direct or line responsibility of listed perpetrators in abuses against individual human rights defenders is often attested to in publicly available documentation, including human rights reporting from international bodies and NGOs, and regime records such as the proceedings of sham trials.

Allowing for individual claimants in such cases may raise constitutional questions linked to jurisdiction, as well as potentially overwhelming the system with a proliferation of international claims. It may therefore be worthwhile to design the framework for claimants in a way that is analogous to the jurisdictional standards of the Justice for Victims of Terrorism Act, which are already well-grounded in legal practice and precedent. It should, however, be more expansive, to allow for claims from the surviving family of victims and not just victims themselves. It should also allow for claims from those with refugee status in Canada and not only those with Canadian citizenship or permanent resident status where the claim fails to meet the statutory test of having a “real and substantial connection” to Canada.

Proposing such a framework need not preclude the transfer of frozen assets for the benefit of a more generalized or collective victim population through an international organization or NGO, but rather intends to allow for the possibility, or ideally the prioritization, of the repurposing of assets for individual victim claimants.

Finally, as a matter of principle and policy, Canada should establish an international contact group for the coordination of Magnitsky sanctions. Beyond ensuring more effective implementation across major economies, Canada should seek to individually and collectively intervene to proactively support the adoption of global Magnitsky legislation in liberal democracies, providing endorsement of the process, and lending experience and expertise in the development of its substance.

In expanding the scope of offenders listed and in creating the capacity for parliamentary oversight, Canada would be bringing its Magnitsky Law in line with international best practices. In allowing for the repurposing of frozen assets for the benefit of victims, Canada would be setting an example of the highest global standards for justice and accountability. And, in establishing an international coordinating group, Canada would continue the effective implementation and internationalization of Magnitsky legislation. Each and all of these endeavours would inure to the benefit of the protection and promotion of human rights and the rules-based international order.

Irwin Cotler is the Chair of the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights, Emeritus Professor of Law at McGill University, a former Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada and long-time parliamentarian. He introduced the first Magnitsky Bill in the Canadian Parliament, and was instrumental in the subsequent unanimous adoption and implementation of global Magnitsky legislation. He was honoured with the Sergei Magnitsky Human Rights Award in 2015.

Brandon Silver is an international human rights lawyer, and Director of Policy and Projects at the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights. In this capacity, he oversees the Centre’s Global Magnitsky advocacy program.