The Canadian Idea That Spawned the Others

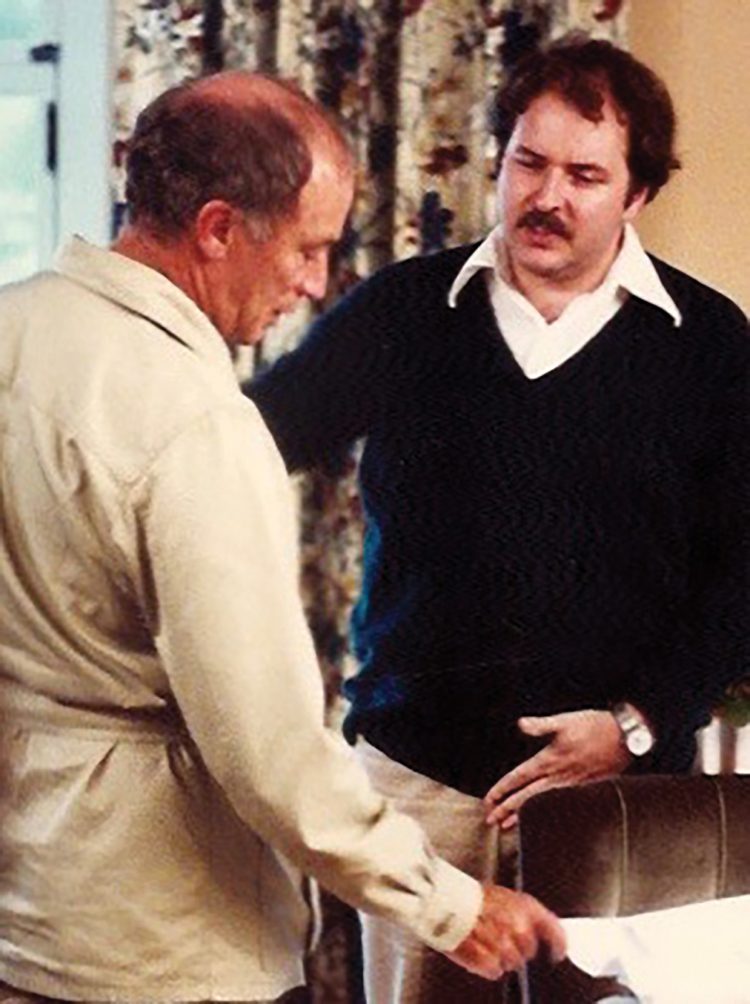

Also, (L to R), Labour Minister Gerald Regan, Clerk of the Privy Council Michael Pitfield, and former PMO aide Michael Kirby, who later served in the Senate. Library and Archives Canada, Robert Cooper photo

Tolerance is a word whose connotation has evolved. As Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has pointed out, we now associate it with a notion of coexistence whereby differences are permitted rather than celebrated. Tom Axworthy, who served as principal secretary to Trudeau’s father, argues that the values of inclusion and pluralism that we now embrace as Canadian had to evolve from tolerance, and without it, there would be no Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Thomas S. Axworthy

Tolerance is the first building block of civility and, as such, it is the pacemaker for a progression along a continuum from state coercion, through intolerance, to toleration, to rights and finally, as philosopher Michael Walzer writes, to enthusiastic endorsement of diversity, inclusion and pluralism. Canada has steadily evolved along that continuum throughout our history until today we are among the most diverse and inclusive countries on earth: 20 percent of Canada’s population is foreign born, and Toronto is one of the most multicultural and multiracial cities in the world: In 2016, over 51 per cent of the residents of Toronto belonged to a visible minority group. A culture of tolerance, nurtured by our history and sustained by the rule of law and our parliamentary institutions, is the preeminent Canadian idea and the foundation upon which all our aspirations and achievements for diversity, inclusion and pluralism rest.

Tolerance is a starter virtue. It denotes “forbearance from imposing punitive sanctions for dissent from prevailing norms” according to political theorist Andrew R. Murphy. It is a virtue based on the recognition, as Voltaire writes in his Philosophical Dictionary, “that discord is the great ill of mankind, and tolerance is the only remedy for it.” A culture of toleration is a set of practices or arrangements that enables peaceful coexistence, or “live and let live”. Its opposite is fanaticism or ideological belief so strong that it makes no allowances and brooks no compromise.

Tolerance is an individual attitude rooted in humility, (we all make errors), and respect, (your views may be as valid as mine). As a multiplicity of voices have risen since Canada’s founding and as we have evolved along the Walzer continuum, the word itself has become contentious. Justin Trudeau, for example, was correct when he stated in a 2018 commencement speech at New York University that tolerance means only that, “I grudgingly admit you have a right to exist but just don’t get in my face.” “There’s not a religion in the world,” Trudeau added, “that asks you to ‘tolerate thy neighbour’.” My argument, however, is that the initial step of tolerance to gaining understanding is all-important and should not be dismissed. If it is absent, conflict is inevitable.

Others, most notably, the authors of The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Women, subscribe to the same definition as Trudeau, while deploring that tolerance has been notable for its absence: that toleration was not part of the colonial past, that Canadian authorities have denied Indigenous peoples the right to exist and that even “present-day Canadian state conduct” is an intentional “genocide” against Indigenous peoples.

In my view, such an exaggeration may have shock value in gaining headlines, but it in no way describes the governments in which I served or the Canada that I know. Still, such debates show that tolerance cannot be taken for granted, even in 2019.

Canada’s history is one of accommodation and compromise, and with each compromise tolerance grew. We are what we are today because of French Canada. The 60,000 inhabitants of the colony of New France refused to be assimilated after the British victory in the Seven Years War and this act of defiance was wisely tolerated by the British authorities (indeed, the first military governor, James Murray, used recently defeated Canadian captains of the militia to act as justices of the peace, giving Canada its first bilingual regime).

This initial wise act of administration was followed by legislation—the Québec Act of 1774—which established the principle that a conquered people should have the right to carry on their own customs and laws. Intelligent adaptation from Britain continued with the Constitution Act of 1791 which brought legislative assemblies to Upper and Lower Canada. Almost immediately, French Canadians showed a talent for politics by using the institution of the assembly to protect their rights and advance their cause.

Canada began down the road of tolerance not because we were virtuous but because of the facts on the ground—a majority of the population was French-speaking. There were also many reversals and setbacks in what Peter Russell calls Canada’s Odyssey, such as the rebellions of 1837 against overbearing elites, the injustices to French Canadians in the Manitoba schools question, the stomping of the Winnipeg General Strike in 1919, the internment of Japanese Canadians in 1942 and the centuries-long betrayal of promises to Canada’s Indigenous peoples. But enlightened political leadership gradually overcame these injustices: Baldwin and Lafontaine developed a partnership to bring responsible government to the colony; Macdonald and Cartier together created the idea of Canada itself; Laurier fought against the sectarian rage of his time and began the mass immigration that has defined Canada; and John Diefenbaker, the first prime minister not from French or English ancestors, fought for “unhyphenated Canadians”—that identity be decoupled from provenance—in his long career on behalf of human rights. And today, at last, Justin Trudeau has made reconciliation with the Indigenous peoples into a national priority.

Growing up in Winnipeg’sNorth End, I saw the culture of tolerance grow firsthand: mine was a polyglot neighborhood of Ukrainians, Poles, Jews and members of First Nations. On the street or in the schoolyard, epithets like “DP” (displaced person), “bohunk” or “drunken Indian” were common. But Winnipeg changed: in 1957, Stephen Juba became mayor, the first Ukrainian to hold high political office in Winnipeg. Ed Schreyer, born to German-Austrian parents, became premier of Manitoba in 1969. Wab Kinew, a member of the Onigaming First Nation, became leader of the New Democratic Party and opposition leader in 2017. The step-by-step progress of Canadians in accepting, then welcoming, diversity has been very real.

The apogée of Canada’s historical arc toward tolerance, human rights and celebration of diversity was the proclamation of the Constitution Act on April 17, 1982 which brought Canada the constitutionally entrenched Charter of Rights and Freedoms. For my students at Massey College, April 17, 1982 is the birth date of contemporary Canada. The Charter is the singular achievement of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. As a young official in the Privy Council office in 1951, he was the note taker as a delegation of human right activists implored Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent to enact a Bill of Rights. Three years later, in 1954, he advocated a charter himself in a brief submitted on behalf of the Québec Industrial Unions Federation to the Tremblay commission arguing for Quebec to “declare its willingness to accept the incorporation of a declaration of human rights into the constitution.” Pierre Trudeau spent a generation arguing that constitutionally protected individual rights, including language rights, were the foundation for ensuring a just democracy. And in April 1982, his vision became Canada’s vision.

But there were many other contributions to the Charter’s evolution and acceptance beyond those of Pierre Trudeau’s. As I’ve argued, tolerance leads to respect, respect leads to compromise, and compromise leads, eventually, to consensus. That is exactly what happened in the great constitutional battle of 1980-82. Trudeau had the initial vision, but Progressive Conservative and New Democratic party members of Parliament greatly improved the Charter in committee. The Charter is a multi-partisan achievement. The constitutional deal of November 1981 was a straight up bargain—the federal government accepted the Alberta amending formula in exchange for the Charter of Rights, though weakened by the compromise-within-a-compromise that allowed a notwithstanding clause to apply to several essential rights.

This was bitterly regretted by Pierre Trudeau, but he accepted the compromise, warts and all. And then when the premiers sought to weaken section 28 on gender equality by applying the notwithstanding clause, the women of Canada, including female members of Parliament from all parties, refused to accept it. They organized marches and delegations across Canada until the premiers finally gave way.

Tolerance, and the virtues it has spawned, have served us well. But does our success have any lessons for the rest of the world? Two authors with very different perspectives think so. Conrad Black, in his magisterial history of Canada, Rise to Greatness, writes that Canada “is one of the world’s ten or twelve most important countries.” Adam Gopnik, in A Thousand Small Sanities writes that Canada is a” model liberal nation.”

We are not used to thinking of ourselves as a foremost nation. But in a world where extreme populism is on the rise, where minorities are still demonized, where religion and ethnic divides are shattering societies, perhaps Canada’s culture of tolerance and our successful adaptation to changing times is something other countries could adopt with profit. Tolerance is a minimalist value—it asks only that you do not coerce and that you remain open to argument. But it leads, in turn, to civility, mutual learning and respect for human rights. In a world full of differing interests and ideas, humility and accommodation are wise and, above all, necessary. That is the Canadian way, and if such an ethic were more widely adopted it would prevent many cruelties.

Thomas S. Axworthy is Public Policy Chair at Massey College, University of Toronto