The Canadian Echoes in Today’s UK Politics

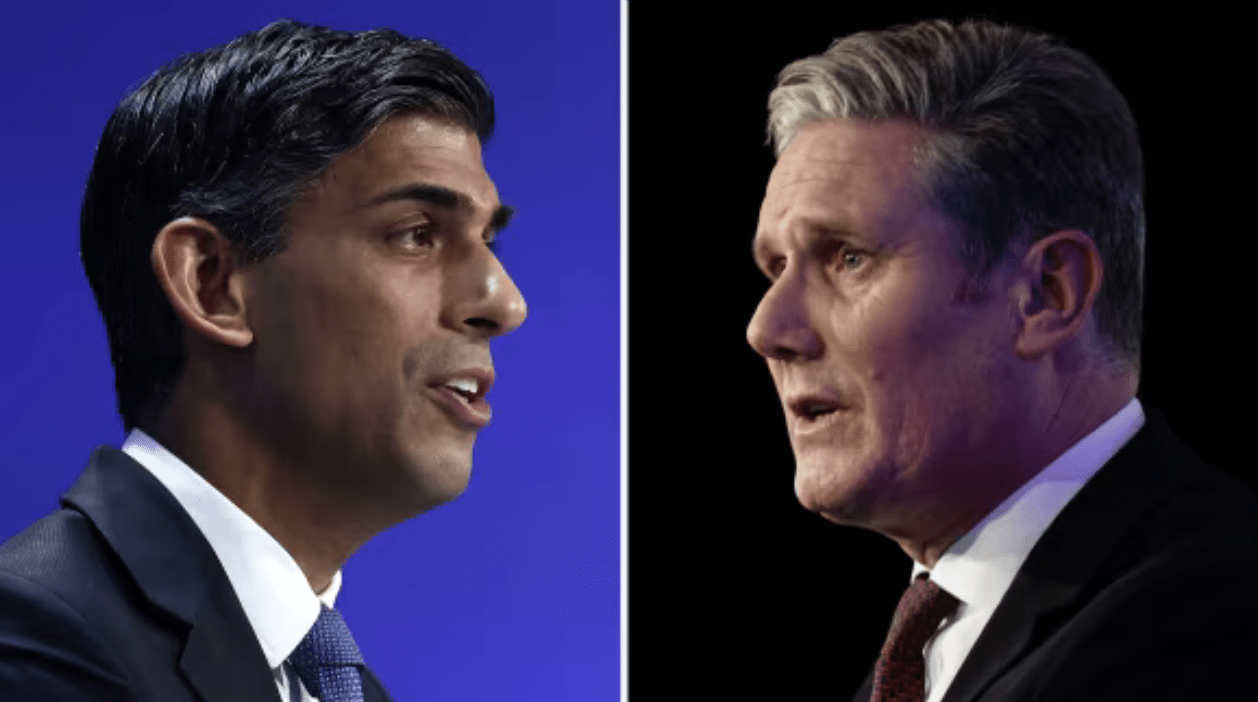

UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Labour Leader Keir Starmer/PA

UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Labour Leader Keir Starmer/PA

By Ben Collins

April 17, 2024

The scenario of a Conservative majority government heading to an historic defeat in a federal election will seem familiar to everyone who knows about the Canadian election of 1993. A similar story looks likely to play out in the UK in 2024. The UK Tories have been in government since 2010, and been in a constant state of flux since the surprise vote to leave the European Union in the 2016 referendum. Brexit has been a destabilizing factor in UK politics since then, with the governing party now on their fifth prime minister since coming to power.

Opinion polls now show a steady and significant lead for the centre-left Labour party currently in opposition. Some recent polls have extrapolated that Labour are on course to win by a larger landslide than Tony Blair secured in 1997. Labour Leader Sir Keir Starmer, the Leader of the Opposition has undoubtedly done a good job in making his party electable again and appealing to both pro-Brexit and anti-Brexit voters. He has tacked to the centre and promised not to implement many changes, especially when it comes to relations with the European Union.

While there is clearly voter fatigue with the Conservatives who have been in government for fourteen years, an additional factor is the governing party losing support to an upstart Reform party, just as Canada’s Progressive Conservatives did in 1993. There is also a looming constitutional referendum for which momentum is building. In Canada, a second Quebec referendum took place in 1995, after the first one in 1980. In the UK, Scotland held its first independence referendum in 2014 and the governing party in Scotland, the SNP have been calling for a second referendum, since England and Wales voted to leave the European Union but Scotland voted to remain. To date, the UK Government have refused to consider all demands for another referendum. The lesson for those who favour Scottish independence is be careful what you wish for, as the second Quebec referendum was narrowly lost by the sovereignty movement, which has, arguably, still not recovered its momentum almost thirty years later.

However, the UK has a second and perhaps more immediate constitutional question, which will need to be answered in the next decade. Northern Ireland voted to remain part of the European Union in the 2016 referendum and the delicate peace secured by the Good Friday Agreement was upset by the implications of Brexit. Since then, the pro-United Ireland Sinn Féin party has become the largest in local government in Northern Ireland and the largest in the Northern Ireland Assembly with the first ever pro-United Ireland First Minister in Michelle O’Neill.

Northern Ireland was created by the UK Government in 1921 to ensure that it had a permanent Protestant and pro-British majority. It now has neither. The Good Friday Agreement states that the UK Government will call a border poll referendum when it appears likely that there is a majority for a United Ireland and that it is for the people of Ireland North and South alone, with no external impediment, to decide whether to vote for Irish unity. In the sort of referendum machinations that will be familiar to Canadians, the current UK Government have declined to set out the criteria that would lead to an Irish border poll being called and the Labour party have given mixed messages over whether they would set out the criteria for a poll, when they are in government. But it will not be something which they can ignore for long if they do form the government after the next election.

The immediate priority must be for preparations to begin in advance of a vote on Irish unity. Brexit has proven to be a case study in how not to prepare for the prospect of constitutional change.

Just as the Labour government of Tony Blair focused on constitutional issues – including Scottish and Welsh devolution — when he won with a thumping majority in 1997, so Labour now in 2024 will be required to make some early decisions on constitutional issues. The prospect of a vote in Scotland may recede in part because the pro-independence SNP is likely on the basis of current polling to lose some of their seats to a resurgent Labour party. But the main factor working against Scottish independence is that there is no defined route to a second independence referendum. The Scottish Parliament does not have the legal authority to call a referendum. For that to happen, the UK Parliament has to consent to a vote taking place.

Northern Ireland is different, as the right to hold a referendum is explicitly stated in the Good Friday Agreement, which brought peace to the region after thirty years of violence. While the right to call a border poll legally rests with the UK Government’s Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, the Irish Government is likely to play a crucial part in this process. An election to decide the structure of the next Irish Government must also be called within the next twelve months. On the basis of current polling, Sinn Féin are likely to dominate the Dáil as the largest party and could lead the next government. Their stated number one priority is the reunification of Ireland. If we find that they hold the positions of First Minister of Northern Ireland and Taoiseach (Prime Minister) of Ireland at the same time, this will accelerate the momentum for a referendum on Irish unity.

The immediate priority must be for preparations to begin in advance of a vote on Irish unity. Brexit has proven to be a case study in how not to prepare for the prospect of constitutional change. Unfortunately, there are currently many factors undermining democracy, but asking people to vote without a clearly defined plan for what constitutional change would entail is something we should all wish to avoid.

While the Irish government will ask the UK government to call a referendum directly, there will also be international requests for support for a vote. Canada played a key role in the peace process and implementation of the Good Friday Agreement through the role of General John de Chastelain on paramilitary decommissioning and Judge Peter Cory in leading an inquiry into state collusion with those involved in violence during the conflict.

In the near future, Canada could be asked to support a call for a referendum on whether Ireland should be reunited. The next UK government will have a bulging in-tray of domestic and international issues that will require urgent action. There will be limited opportunities to garner goodwill from neighbours close and far who have unwillingly been drawn into the Brexit saga through trade negotiations and the destabilizing effect this has had on relations across Europe. At a time when there are wars in Ukraine and in Gaza, this is far from ideal. But the UK Government acceding to the request for a referendum on Irish unity and constructively enabling the outcome in the event of a vote for reunification, is a rare opportunity to show that it is once again a trusted and reliable partner on the international stage.

Ben Collins is a Belfast-based communications consultant and author of the book Irish Unity: Time to Prepare.