‘The Camera is an X-Ray Machine for the Soul’: Debates and the Likeability Factor

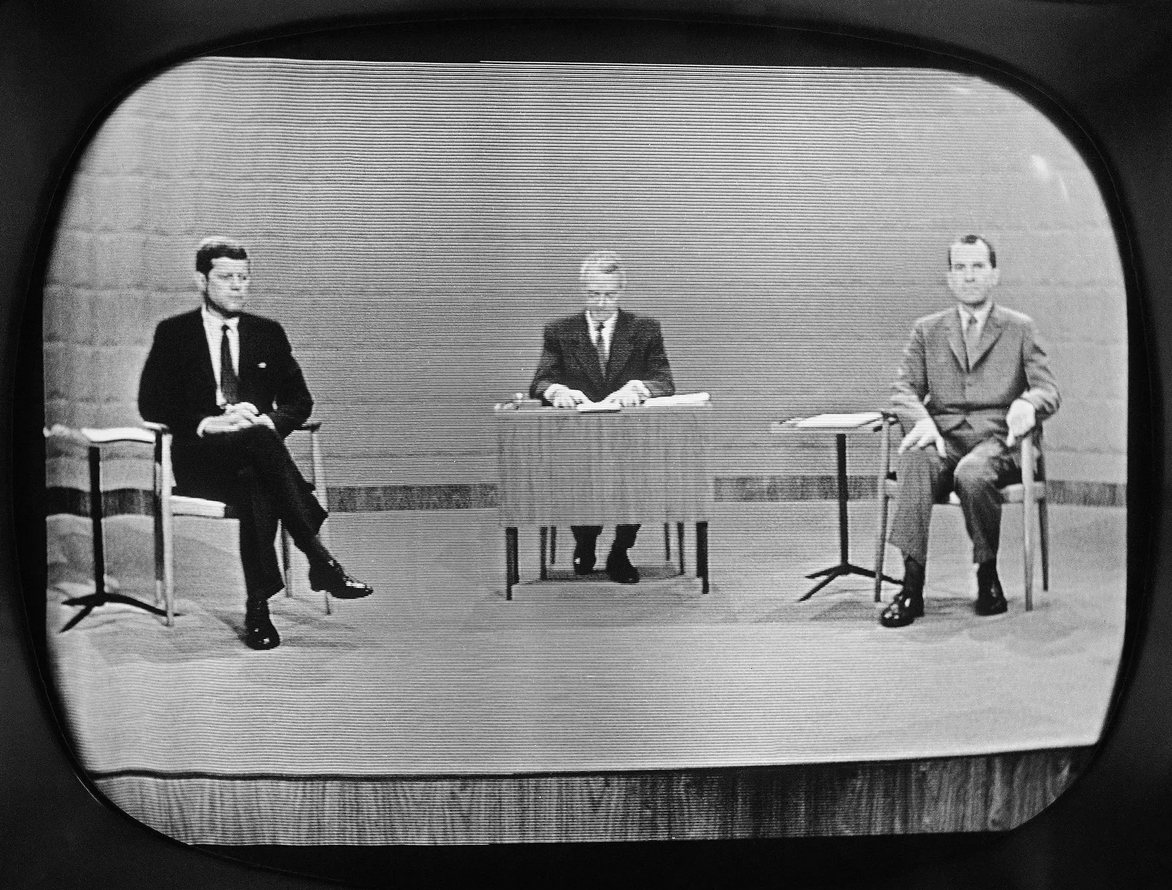

Senator John F. Kennedy and Vice President Richard M. Nixon with moderator Howard K. Smith in the first presidential debate on Sept. 26, 1960/AP

Senator John F. Kennedy and Vice President Richard M. Nixon with moderator Howard K. Smith in the first presidential debate on Sept. 26, 1960/AP

Apr 14, 2025

“The camera is an X-ray machine for the soul. It sees what’s authentic and what’s fake.”

David Gergen, presidential adviser to presidents Nixon, Ford, Reagan, and Clinton.

Much ink has been spilled offering explanations for how the Liberals have replaced a 25-point deficit with a 4- or 5-point advantage – all in a matter of a few months.

No doubt, part of the answer has to do with Justin Trudeau deciding to step down. That decision let the air out of the fatigue problem that many incumbent governments face.

For voters who want change, now they have another option.

Also important is how much the issues on the minds of Canadians have shifted — Donald Trump is the biggest economic issue and a more worrying risk than people have felt in a long, long time. Now, fewer people are going to vote because of anything that happened in the last several years — a lot more want to know “what should we do now?”

That tariffs and geopolitical chaos have put the relevant skills and experience of Mark Carney and Pierre Poilievre front-and-centre is obviously making a difference, too. One’s an economist with deep knowledge of global interrelationships. The other’s a career politician who dismisses the value of global relationship building.

But as important as those factors are, I don’t think they fully explain what we are seeing today.

With the leaders’ debates looming this week, I’m reminded of another quote from a first-rate American political consultant, Mark McKinnon, who said “The first 30 seconds on camera are the debate for many viewers. After that, they’re just watching their impression confirm itself.”

Studies show that it takes milliseconds for people to decide if they like someone or they don’t. Listeners form judgments within half a second of hearing a voice. And our first judgments often stick.

When we observe people running for high office, we watch the way they walk, listen to how they talk, notice if they seem nervous or confident, have a kind or sincere look on their face when meeting someone, or seem to be performing a role.

Years ago, for a politician I won’t name, I did some research that highlighted for me how differently people react to a politician who seems confident that the future will be better, compared to one who is pretty sure we’re all in for a rough ride.

People want to be led by someone they like. Someone they feel they can trust to do the right thing. Someone who is a good person. This only sounds trite because we don’t talk about it very often.

If a picture is worth 1,000 words, a picture of a politician whose face conveys confidence is worth 10,000.

This is human nature. It’s about what we look for in leaders. We’re not usually relying on an IQ test or a policy book, although intelligence and ideas both obviously matter. It’s usually something more basic than that.

People want to be led by someone they like. Someone they feel they can trust to do the right thing. Someone who is a good person.

This only sounds trite because we don’t talk about it very often.

In tight races, a lot of the variation in support among late-deciding voters comes down to likeability. And when we form a good first impression, we think the politicians we like perform better in interviews and debates – our instinct for confirmation bias is very strong.

In the 11 US presidential elections since 1980, the more likeable candidate (based on polling results) won 10 of those elections. The magnitude of the likeability gap often impacts on the size of the victory, and the length and width of the coattails.

The camera staked its claim as an X-xay machine for the soul during the first televised presidential debate, between Vice President Richard Nixon and Senator John F. Kennedy on September 26, 1960. Nixon’s famously sweaty, shifty debate performance contrasted sharply with Kennedy’s relaxed, cool demeanour. Nixon lost the likeability contest.

People have had a couple of years to decide whether they like Pierre Poilievre. They’ve had weeks to form a judgment about Mark Carney.

Today’s polls show a sizeable personal likeability advantage for Carney – considerably wider than the advantage of the Liberal Party over the Conservatives. For sure, some of it is about perceived competence and resumé. But I believe some softer human variables that people see are also playing a role – a mix of confidence and humility, a serious person who also has a warm laugh, a hard worker with a playful side too. Someone who seems in it for the best reasons, and is asking for, not expecting your vote.

If some of these attributes seem more challenging for the Conservative leader, it is probably because of the posture he manufactured for himself. He made people feel that if they voted Liberal he doesn’t respect them. He conveyed a belief that because Trudeau was so awful (in his view) that you’d have to be an idiot not to vote Conservative. He happily posted videos showing him being snotty and superior with journalists who asked him questions.

He seemed to take pleasure in proving that he could win without being likeable.

We’ll see in a couple of short weeks how this election turns out. But at this point, the gap in likeability is the variable that I would watch more closely than any other.

Bruce Anderson has been a pollster, strategy and communications advisor for more than 40 years. He is a frequent commentator on Canadian politics and public policy including on The Bridge podcasts. He is a founding Partner and Chief Strategy Officer of Spark Advocacy. Over the years he has worked with Progressive Conservative and Liberal politicians but has not been active in campaigns for several election cycles, until this one. He is an active supporter of Liberal Leadership Candidate Mark Carney.