The Bilateral Value of Our Foreign Policy Brain Trusts

In Ottawa and in Washington, at Fort Pearson and Foggy Bottom, there are career diplomats and policy experts who make it their business to know each other’s countries in ways that can make tourists, exporters and even residents seem uninformed. Political leaders rely on them for accurate information and competent implementation. Sarah Goldfeder, who served as a US diplomat in Ottawa, provides a window on the state of the State Department.

Sarah Goldfeder

Canada and the United States share a system where the elected executive identifies political allies to function in the top levels of the executive branch departments. The idea is that policy trickles down from the top—in having allies who share the elected leader’s values and vision, the machinery of government is directed from the top deck, much like a large ship.

The reality is that as much (or more) policy trickles up from the layers of bureaucrats that dedicate their careers to public service. The continuity the senior officials and their teams provide is critical to the governance of both countries.

Foreign policy, trade policy, security and defence policy, all require commitments to long-term strategies that can sustain and go beyond changes in political agendas. A well-tuned and empowered bureaucracy can both implement political agendas and, importantly, serve as institutional memory and provide momentum. A healthy bureaucracy is committed to the Constitution, country, and fellow citizens, and provides an understanding of the “now” in view of the past and the capacity to draw a map to the future.

The more complicated the area of government policy, the more necessary experts in the machinery of government become, and nowhere is that truer than in foreign policy. Foreign ministries, whether the US Department of State or Global Affairs Canada, are collectives of expertise. Much of that collected expertise is learned on the job, with on-the-ground training being a critical factor in the understanding of how other governments, their civil societies, and foreign policy objections mesh together. These departments develop language talent, geographic expertise, issue mastery in multilateral organizations, trade, intelligence gathering, security and migration, among other specialties. The talented officers serving in these positions have the capacity to distill complex internal governance issues happening in countries around the world into condensed, high-level briefing notes that provide the first glimpse of complicated issues to many of the political staff supporting cabinet level officials. They are able to identify threats to national interests early, as well as advice and counsel on steps forward.

In the wake of the US election of 2016, there was a feeling in Canada and the rest of the world that a Trump presidency would so upset the norms of governance that the ways in which countries work together would have to be entirely re-thought. The reality was that in many ways, the American bureaucracy remained on course. They foiled some attempts to walk back long-established policies and even the rejection of science as a basis for others, but there remains work to be done in reorienting the country on a more democratic and equitable path.

The world witnessed first-hand the tension between the political leadership of the US Department of State and its career foreign service officers and specialists during the Trump administration. The tension between the seventh floor (the floor of the State Department’s eight-story Harry S. Truman Building that houses the politically appointed leadership, including the office of the secretary of state) and the layers of bureaucracy that support it was obvious in the wholesale rejection of the career officers by Rex Tillerson (Secretary of State 2017-2018) and then in the exploitation of them by Mike Pompeo (Secretary of State 2018-2021). The reality is that the global processes of diplomacy continued, perhaps not as usual, but just enough.

Canada has had its own experience in navigating similar tension—most recently and publicly perhaps in the Department of National Defence, but also within the foreign policy establishment. There is a prestige in being the minister of Foreign Affairs, underlined by functioning as the primary representative of the prime minister in meetings with allies and others. Without the guidance, preparation, and expertise of the battalion of Canadian diplomats and public servants located at the Pearson Building and across the world, the political leadership would be overwhelmed by attempting to understand the nuances of regions, systems, and leaders. At times, political actions in the guise of diplomacy are seen as a necessity of domestic politics, and the well-trained and clear-eyed bureaucrats of both Canada and the United States understand how that works. The tensions arrive when the political staff does not recognize that the department can be helpful in navigating how the diplomatic meets the political, and in many cases, in developing plans for damage control.

The dance between politics and the public service works best when cabinet-level officials understand that in taking on the mandate of a department, they are taking on the care and feeding of the individuals who serve it. No one did this better than Colin Powell (Secretary of State 2001-2005). From the moment he arrived, Powell looked at the people of the department and asked, “What can I do for you?” Actually, what he said was, “You can’t be a good chief foreign policy advisor to the president unless you are also deeply involved in and concerned about the welfare of the people who are executing the foreign policy of the president.” And he did that, through introducing a leadership component to professional development and by continually implementing mechanisms best described as belonging to human resources. Whatever his legacy as a diplomat, there is no doubt that those who served under Powell valued his focus on the people of

the department.

The US Foreign Service stands at a crossroads. During the past administration, many have written of the potential ramifications of losing the talent and knowledge encompassed in the Department of State. On July 2nd, three Masters candidates at the Harvard Kennedy School released the report, The Crisis in the State Department. The report outlines the potential dangers of above-average attrition rates in the Foreign Service. The research concludes that more than 1/3 of current personnel are actively looking to leave the department. Decades of mismanagement have combined with the open hostility of the Trump years to leave the bureaucracy broken and in desperate need of repair.

The dangers of losing the expertise of one-third of the department could be crippling. As if the loss of the cumulative knowledge and experience aren’t significantly devastating on their own, there is the snowball effect on morale. Five years ago, I joined a Facebook group for transitioning Foreign Service officers. At the time, I had recently left the department and thought I could be a helpful sounding board for people looking for career fulfillment post-State. What started as a handful of colleagues swapping administrative hints and job postings quickly grew to more than 2,000 members at all stages of departure; for comparison, there are 8,000 active foreign service officers.

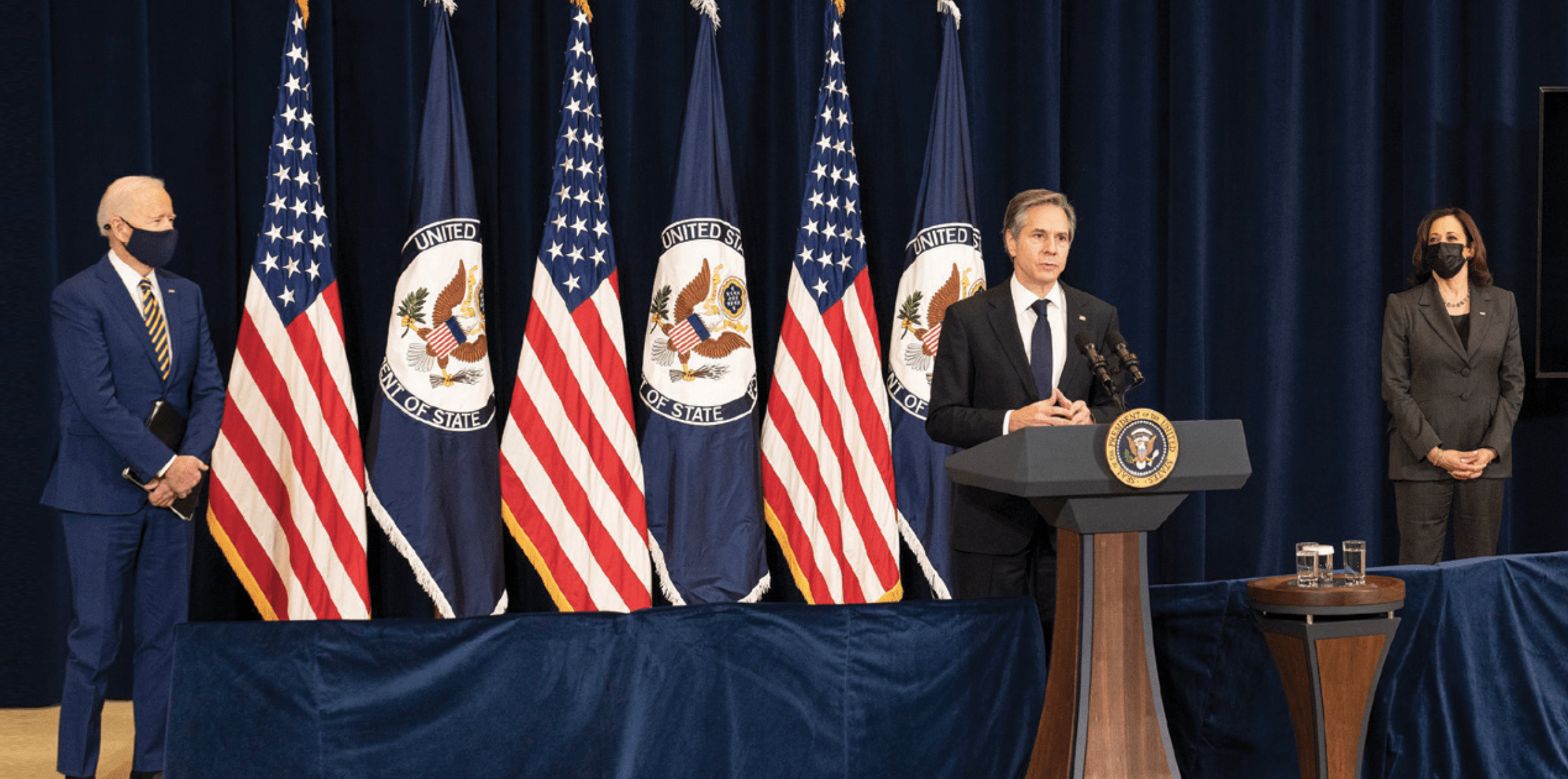

Losing your bureaucratic talent is a major failing for any government. The emphasis that Secretary Antony Blinken has placed on retention and even re-activation of former Foreign Service officers is reflective of his understanding of the importance of the underlying issues. We can hope that is sufficient—the accumulated understanding of the world, all its leaders, factions, problems, and sensitivities, is invaluable. The stability of the underlying public service in the United States provided us with a government that could relatively easily and quickly pivot to the historical priorities of each department in the months since the Biden inauguration.

Tensions will continue to exist between the political leadership and the officials in every department. To dismiss those as fears over job security or general malaise is short-sighted. Political leaders share certain personality traits, as do public servants—and while nothing is universal, in general, public servants go into government out of a belief in the system and in the importance of their area of expertise. Whether that be environmental policy, the construction of sustainable budgets, energy development, industrial policy, immigration, or the very safety of the country itself, the professionals that gird the government are responsible for the careful implementation of political agendas. The sub-text is that those professionals also understand what works, what could work, and how to ensure that policies are implemented in ways that protect the national interest of their fellow citizens.

To ensure that policy can be implemented, that governance can continue while addressing issues of importance to the Biden team, must be a feat not of grandeur, but of incrementalism. The government of the United States of America is often compared to an aircraft carrier—difficult to turn on a dime.

Changing course in a machine this complex and cumbersome requires time and adjustments that are often invisible to the eye. Those are exactly the kind of adjustments that the public service does best.

Contributing Writer Sarah Goldfeder is a former career State Department officer who served as an advisor to two US ambassadors to Canada. She is currently manager of government relations at GM Canada.