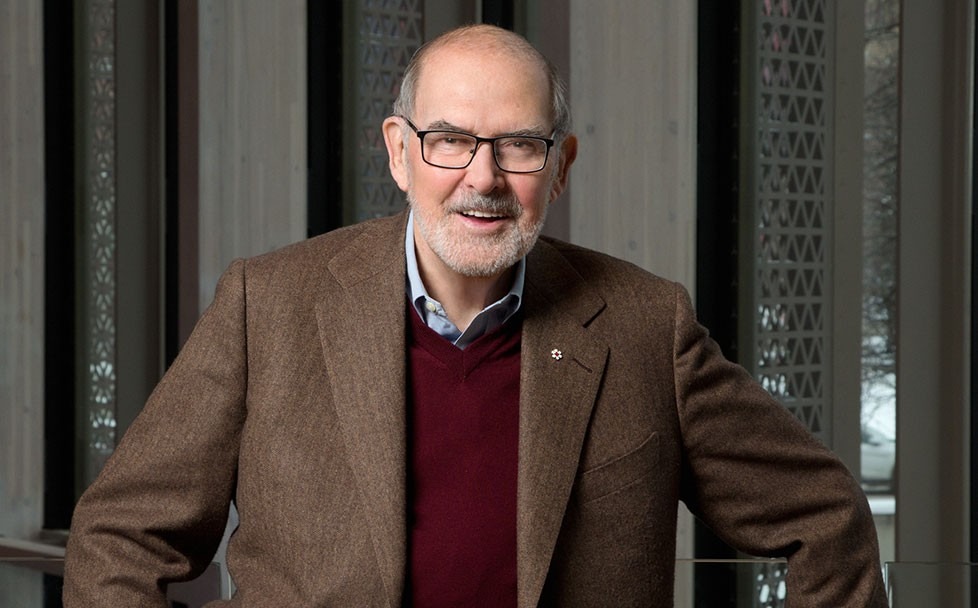

The Big Vision and Big Heart of Peter Herrndorf

Rosemary Thompson

February 19, 2023

Peter A. Herrndorf’s love of Canada infused everything he touched. He believed that artists and journalists could help us understand the great expanse of our country—to bring us together to define what it means to be Canadian, in all our complexity and beauty.

He dedicated his own life to championing the artistic life of the country through broadcasting, publishing, educational television and, finally, through the performing arts at the National Arts Centre.

He did it with big vision and big heart.

When we tried to find the perfect description of his vision for the NAC’s role in the country, it was crystallized into this phrase: “Canada is our stage.”

It meant that what happened on the stages of the national capital was important. More important still was working with artists and arts organizations across the country to build opportunities for the performing arts in every part of Canada.

On November 3, 2009, the second day of my job at the NAC as director of communications, Peter took me out for lunch at Le Café, and gave me a handwritten list of 10 things he wanted me to work on. He was very clear about what he wanted to achieve, and how to work with the incredibly talented team he had assembled to turn his vision into a reality.

I looked at the list again today – the day after his death— and nearly everything he wrote down was realized. On the list were projects such as: launching Prairie Scene, an ambitious festival featuring hundreds of artists from Manitoba and Saskatchewan; the National Arts Centre Orchestra tour to Toronto’s Roy Thomson Hall; sending the Orchestra to Vancouver for the 2010 Cultural Olympiad; and the unveiling of a sculpture of the legendary jazz pianist Oscar Peterson that would sit outside the NAC on the corner of Elgin and Mackenzie King. (It would be unveiled by Queen Elizabeth II in June 2010, in front of a crowd of 10,000 people).

Peter didn’t have a computer, or a cell phone in those days. He communicated through handwritten lists and notes, telephone calls, and in-person conversations. While some may have thought that was a throwback, I always believed it was the secret of his success.

That list alone reveals what a gifted leader we have lost. And it doesn’t include the founding of the Indigenous Theatre which came after many years of thoughtful consultations and conversations with Indigenous artists who made it happen.

Peter would write these lists for everyone at the NAC when he was home in Toronto on the weekends with his family. When he wasn’t going to Raptors games with his son Matthew, or Blue Jays games with his daughter Katherine, or having dinner with his wife, Eva Czigler, he was thinking about what he wanted to achieve and how his team in Ottawa could help him do it.

Peter didn’t have a computer, or a cell phone in those days. He communicated through handwritten lists and notes, telephone calls, and in-person conversations. While some may have thought that was a throwback, I always believed it was the secret of his success. Peter was never distracted. His only focus was the people who surrounded him. He listened carefully to how they were doing, what they needed, and how he could help them succeed.

Peter wanted to be surrounded by what he called “superstars”. He loved baseball, and in many ways, he was like a high-powered general manager. He recruited the very best people from across the country. He gave them some direction. And then he let them fly. He managed creative teams with a very light touch. He set his expectations at a high level and would check in with you from time to time to see how you were doing.

Checking in often happened as he walked into the building on Mondays when you could hear his booming laughter all the way down the hall. He would peek into the National Creation Fund office to find out what new productions they were financing. Next stop was the NAC Foundation to hear what incredible donation had come in over the weekend. Then he would check into the Communications office to see what media we had lined up. He would say, “I want embedded media on the Orchestra Tour,” to which I’d reply, “Peter, media embed on election campaigns and armed conflict, not typically Orchestra tours.” He’d smile, and I’d visit every editor and publisher in Canada to convince them to send media to cover our artistic tours. On it went until he reached his office at the end of the hall.

He knew everyone by name. He knew about their families, their joys, their struggles. He shaped a culture of belonging at the NAC that I’ve never seen duplicated anywhere else.

Peter also spent a lot of time backstage in the Green Room and in the staff cafeteria filled with musicians, dancers, technicians, actors, choreographers, and stage hands. He listened to how their rehearsals were coming along, responded to any challenges they were having, and cheered them on as a co-conspirator to their success. It’s also how he learned about how the place worked, what the issues were, and how he could help.

He knew everyone by name. He knew about their families, their joys, their struggles. He shaped a culture of belonging at the NAC that I’ve never seen duplicated anywhere else.

He cared about everyone at the NAC, from the security guards to the kitchen staff, to the artists that are the NAC’s beating heart. When he was proud of something you did, a handwritten note would arrive on your desk. If a team really hit it out of the park, he’d send a bouquet of flowers.

Such big vision. Such big heart.

As a Harvard Business School graduate, Peter Herrndorf understood the value of building great teams, and seeing them realize extraordinary things. That’s how we built the pitch for the architectural and production renewal of the NAC. After a national competition, he hired the architectural team at Diamond Schmitt Architects, quietly built a case for support, and began the diplomatic and public affairs mission that ultimately led to two back-to-back investments — by the Conservative government in 2014 and by the Liberal government in 2016 — that totaled $225.4 million. The transformation changed the NAC from a windowless concrete bunker into a sun-filled, transparent, vibrant and accessible institution that opens up to the capital today.

Upon learning of his death, many of his colleagues at the NAC gathered this weekend to share memories, tears, and hugs to honour a leader we will never forget. When Peter stepped down from his role as President and CEO of the NAC in 2018, I remember asking him what he would miss the most. I thought he might say the founding of the Indigenous Theatre, the NAC Orchestra’s tours to Europe or Asia, the two royal tours, or the monumental opening of the new building.

What he said was surprising, and so revealing.

“I’m going to miss being in the main foyer at intermission, when all of the halls are full, and the audience pours out, and they are laughing, or deep in conversation, and enjoying the performances in all of our venues. That is my favourite moment at the NAC, when there are thousands of people here, enjoying the performing arts.”

This weekend the NAC lived up to Peter’s fondest wish. All day long the place was filled with kids attending a lively arts festival. And in the evening, thousands of audience members were enjoying the very best in music, dance and theatre.

For all of us who worked with him, it is incredibly difficult to say goodbye. But what we can do is remember his lists, his encouraging handwritten notes, his legendary Christmas cards, and his habit of singing to you on your birthday.

We also need to remember his belief that journalism, public broadcasting and the arts play a critical role in the life of the country, and in helping us understand each other as Canadians.

And we must follow the path he forged for us, and confidently step forward, following his example to build a better future for Canadians.

We need to remember his vision, and his very big heart.

Rosemary Thompson is the Executive Director of the Coalition for a Better Future and served as the Executive Director of Communications, Public Affairs and Corporate Secretary of the National Arts Center from 2009-2018.