The Big Sulk? China’s ‘Inward Turn’ Takes a Holiday

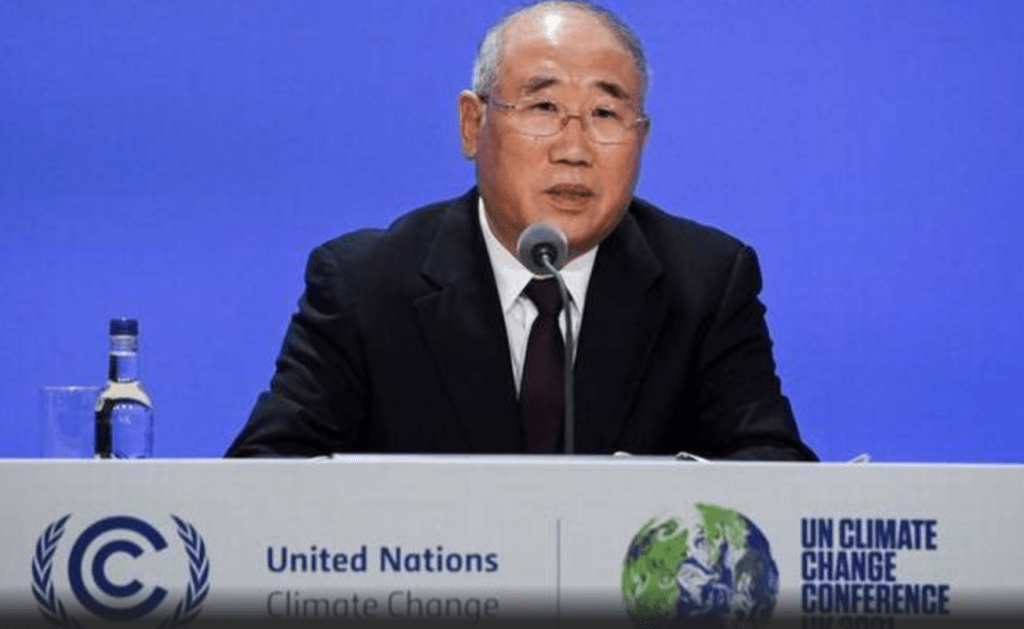

China’s chief climate negotiator Xie Zhenhua during a joint China-US statement on climate action at COP26 on November 10, 2021/Reuters

Lisa Van Dusen

November 11, 2021

The announcement in Glasgow Wednesday that the United States and China have agreed to work together on cutting greenhouse gas emissions over the next decade was a surprise.

The China-US Joint Glasgow Declaration on Enhancing Climate Action in the 2020s was a shock (except, obviously, to the signatories) not just because the absence of President Xi Jinping from COP26 had doused expectations of any major collaboration news but because it veered from the latest China narrative.

That read on China’s 21st-century evolution — that Beijing has responded to international disapproval and the unexpected post-Trumpian detour of Joe Biden’s pro-democracy, anti-authoritarian presidency by taking its marbles and staying home, as it were — has lately emerged in headlines from the Economist, to the Wall Street Journal to the Financial Times, among others.

China’s observed inward turn is more than just a reaction or overreaction to COVID-19 as both a public health crisis and contagion-containment public relations disaster. After two decades during which Beijing systematically fought any post-internet blooming of democracy at home by undermining democracy not just at home but everywhere else, it may now be not so much trimming its sails as tacking downwind.

In the Financial Times November 5th piece China turns inward: Xi Jinping, COP26 and the pandemic, Jean-Pierre Cabestan, a professor of political science at Hong Kong Baptist University, said, “There have been many forces at play in China for some time, all heading in the same direction: decoupling [from the west] and isolating China [to] better protect her from foreign hostile forces or ideas.”

That decoupling seems more propitious than it otherwise would for the west because China’s pre-decoupling engagement with the liberal world order over the past two decades has been defined most consequentially by its corruption of multilateral institutions, industrialized hacking of intellectual property and leveraging of its Belt and Road infrastructure project to expand authoritarian norms across the globe.

The outward-looking phase of China’s post-millennial, post-internet posture toward a post-9/11 status quo did nothing to showcase the advantages of an expansionist Beijing for anyone in the world other than international businesses whose intellectual property hadn’t already been plundered, aspiring authoritarians hankering to be plucked from obscurity for their close-ups and corrupt intelligence interests seeking cover for the surveillance-state degradations of human rights and democracy norms you can get away with when change is rationalized by the debt-trap sway of an aspiring superpower.

After two decades during which Beijing systematically fought any post-internet blooming of democracy at home by undermining democracy not just at home but everywhere else, it may now be not so much trimming its sails as tacking downwind.

In January 2019, the US intelligence community explained its apparent absence without leave from this operational crucible by attributing it to a protracted bout of Rip Van Winkle narcolepsy. “While we were sleeping in the last decade and a half, China had a remarkable rise in capabilities that are stunning,” then-Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats told the Senate Intelligence Committee.

This week, in the Wednesday Bloomberg piece China is evading US spies and the White House is worried, an intelligence community sufficiently awake to generate a tactical content drop unveiled a whole new suite of rationales for its inability or unwillingness to preoccupy itself with China, this time including Communist Party opacity, the purging of CIA assets in China prior to Xi’s ascension to power more than a decade ago, and a shortage of Mandarin speaking agents — pretty much everything but “the dog ate my homework” — which is a little bewildering coming from the most well-funded, borderless, technologically omniscient intelligence leviathan in history.

During the four years of Donald Trump’s presidency, an alchemy of exposition, hostility and belligerence took shape whereby Beijing’s anger at having to defend actions, motives and intentions that had been unquestioned for more than a decade produced a tantrum cycle of coercive diplomacy, hostage diplomacy, “wolf-warrior” diplomacy and other euphemisms for rogue-state aggression. It was an overreaction to the end of an unsustainable strategy.

But in a sane world — perhaps where the collective-lunacy response to this century’s innovations in covert power games had already exhausted itself — China’s response to these events would be something other than shifting from undermining democracy worldwide to re-focusing on suppressing rights and freedoms within its borders, which is simply a way of doubling down on subjugating human beings to the consolidation of absolute power. Withdrawing from multilateral forums and turning away from global trade in favour of the “dual circulation” shift from exports to its domestic market as yet another manifestation of isolationism also won’t address the problem.

And the real problem is that China has been pursuing superpower status conditional on a vacuum of moral domestic policy, moral foreign policy and moral judgment from anyone else, which is why it has deemed truth an asymmetrical existential threat. If Beijing were the only power player functioning within that reasoning these days, the content sphere wouldn’t still be riddled with propaganda, to put it politely. If turning inward after two decades of actively undermining a competing system now means leaving that task to western interests with their own reasons to pine for the death of democracy, Beijing can always join the rest of us in the poncho seats for that spectacle.

Wednesday’s announcement in Glasgow bodes well for the possibility that China will ultimately segue from an unsustainable path of frictionless corruption to an unsustainable path of relentless belligerence to an unsustainable path of defensive isolationism to, finally, something more productive and worthy of its people. Perhaps the virtual meeting between Joe Biden and Xi Jinping on Monday will tell us more.

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor of Policy Magazine. She was Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.