Strike One!

Douglas Porter

April 21, 2023

Just two weeks ago, we intoned that cracks were forming in the foundation of the global expansion. Well, those cracks are still mostly of the hairline variety. True, there are increasing indications that the U.S. economy is losing momentum, but next week’s GDP report is likely to reveal a respectable 2% pace for Q1 growth. And, most of the surprises in the rest of the world continue to land on the high side of downbeat expectations. With growth generally holding up better than expected so far in 2023 for most economies, prospects of rate cuts have been pushed further down the road, and small odds of further near-term rate hikes have been re-priced in for both the Fed and the Bank of Canada. Against this backdrop, markets mostly fought to a draw this week, impressed by a resilient economy, but concerned that it won’t last, and encouraged by easing inflation, but fretting that progress is too slow.

One of the more important releases of the week revealed surprisingly sturdy Q1 GDP growth in China. The re-opening drove a 2.2% quarterly advance (or roughly 9% annualized), which lifted output 4.5% above year-ago levels. The next quarterly report will have an even friendlier year-on-year comparison, as Shanghai was dealing with lockdowns a year ago, pointing to an even bigger bounce in Q2. Accordingly, we have bumped up our annual forecast for China’s growth rate by more than a full point to 5.8%. This solid performance masks a notable split between domestic spending—retail sales fired up 10.6% y/y in March—and industrial production—which only managed a 3.9% y/y rise for the same month.

A slightly different version of that split is evident in many other major economies, running down a ‘services versus manufacturing’ line. The initial readings from April PMIs in the Euro Area flashed a nice upside surprise on services (to a solid 56.6) versus a downbeat factory result (a sickly 45.5). The U.K. seconded those emotions at 54.9 (services) versus 46.6 (factories). Even Japan showed a similar split (54.9 vs 49.5), albeit with a generally healthier manufacturing backdrop. European consumer confidence is firming, with an assist from much calmer energy prices—Dutch gas prices are now less than a third of last year’s average. And, German producer prices are up “only” 7.5% y/y, after hitting a post-war peak of above 40% last summer. Reflecting these less dire conditions, we have further nudged up our forecast for Euro Area GDP growth to 0.9% for 2023, from flat at the start of the year.

The upward revision to our estimate for European GDP this year largely mimics changes to our call for North America. While we made no changes this week, those forecasts have also been lifted from zero growth at the start of 2023 to 1.0% now for both economies. In combination with the upsized calls on China and the Euro Area, we are now looking at global growth of 2.7% this year. That’s down from last year’s 3.4% advance, and below the medium-term average of 3.25%-to-3.50%. But, given the bountiful talk about recession in the past six months, that’s not bad at all.

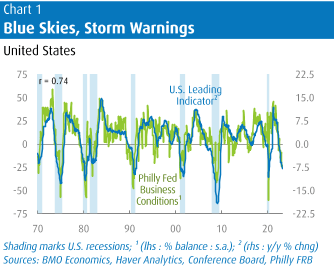

Even so, our forecast still assumes a shallow downturn in the next two quarters in North America. While current indicators remain surprisingly sturdy, almost all forward-looking metrics are warning of an impending slowdown. For example, the Philly Fed’s Business Conditions Index, which has a 55-year history, fell to its lowest level since 2009 in April (aside from the depths of the first two months of the pandemic). At -31.3, the index has never been as low at any time outside of recession periods; for context, the lowest non-recession result was -20.8 in June 1995. The Conference Board’s leading indicator is sending an almost identical message, falling 7.8% y/y, or a degree of difficulty never witnessed outside of a recession (Chart 1).

Despite these rather loud warning bells, there is no debate that this is a truly unique cycle, and it’s entirely possible that many of the traditional economic measures just can’t properly capture the underlying realities. To wit, in past cycles, the chart shows that both leading indicators and the Philly Fed were only this weak when the U.S. economy was already knee-deep in recession. And, it’s pretty clear to most that we are patently not in a recession yet, whether one looks at the job market, spending patterns, or even the message from financial markets. Putting an exclamation mark on that point, S&P’s U.S. PMI rose to its highest level in almost a year in April.

Despite these rather loud warning bells, there is no debate that this is a truly unique cycle, and it’s entirely possible that many of the traditional economic measures just can’t properly capture the underlying realities. To wit, in past cycles, the chart shows that both leading indicators and the Philly Fed were only this weak when the U.S. economy was already knee-deep in recession. And, it’s pretty clear to most that we are patently not in a recession yet, whether one looks at the job market, spending patterns, or even the message from financial markets. Putting an exclamation mark on that point, S&P’s U.S. PMI rose to its highest level in almost a year in April.

Amid the ongoing resiliency, Bank of Canada Governor Macklem went so far this week as to mutter the words “soft landing”, a phrase he has mostly shied away from in recent months. Canada will also get an early read on Q1 GDP when the monthly output figures are released next Friday. While conditions cooled after a blistering January, we still expect a 0.2% rise for February GDP (flash estimate was 0.3%). Even with a small pullback in March—and retail sales look to be down 1.4% that month—we are calling for Q1 growth of around 2.5%, a tad above the decent U.S. trend.

The near-term outlook will be dented by the massive public sector strike, which began this week. Those walking off the job account for roughly 0.6% of the Canadian workforce, and spillovers to trade and travel could potentially clip GDP by 1%, depending on how long the job action persists. Presumably, the strike will not go on for long, and will mostly just land a temporary blow on April GDP. However, the very public wage negotiations come at an incredibly delicate time for the inflation backdrop, potentially setting the tone for a vast array of settlements elsewhere. The PSAC union seeks a 13.5% raise over three years (4.5% per year), which is based on inflation for the 2021-23 period, while Ottawa has countered with 9%, with other concessions.

Canada’s CPI was right on consensus expectations this week at 4.3% y/y for March, one of the lowest rates in the OECD, and apparently headed for 3% in coming months. But getting inflation sustainably back into the 1%-to-3% target zone could be a challenge, as even short-term metrics of core inflation are stuck above 3%. A wave of wage settlements in the zone of 4% or higher across the economy, at a time of almost no productivity growth (0.2% over the past five years), could put a hard floor under inflation and make the Bank of Canada’s job of getting back to target that much more difficult. That reality, along with signs that the economy retains much of its surprising resiliency, reinforces our point that rate cuts are probably not a story for this year.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.