‘Still a Place for Daring in the Canadian Soul’: How to Lead on Climate Change

Pollution Probe

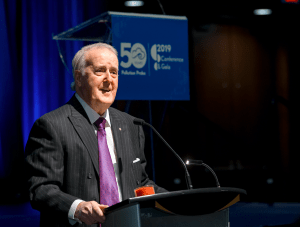

Former Prime Minister Brian Mulroney was presented with the 2019 Pollution Probe Environmental Leadership Award at the 50th anniversary Gala Celebration of Pollution Probe in Toronto on November 19. In his acceptance speech, he reflected on the accomplishments of his tenure on acid rain and GHG emissions, among other environmental issues, and shared his prescription for leading on the controversial questions of our time.

Brian Mulroney

Nov. 20th, 2019

I came to office as Prime Minister determined to place the environment at the top of our national priorities. Why? Well, for many reasons, but when I was young we used to swim in the waters of Baie-Comeau. Over time, they became completely polluted by the pulp and paper mills in the region. And so, no one swims in Baie-Comeau anymore. I had seen the same thing happening in hundreds of communities across Canada and decided to act.

Lorsque j’étais très jeune, aller jusqu’au bout de la rue Champlain pour se baigner dans la baie Comeau, d’où ma ville natale a tiré son nom, était un plaisir.

Aujourd’hui, là où nous nagions, se trouve un parc. Les déchets de l’usine à papier se sont accumulés, là où jadis l’eau était claire. Et plus personne ne se baigne dorénavant dans la baie.

From the perspective of our government, the environment was a priority from the day we took office. We knew we had to lead by example at home, and engage the international community on environmental issues that knew no borders.

At home, we established eight new national parks, including South Moresby in British Columbia, and our Green Plan put Canada on a path to create five more by 1996 and another 13 by 2000.

We began the long overdue cleanup of the Great Lakes, St. Lawrence and Fraser rivers, and we launched the Arctic strategy to protect our largest and most important wilderness area — the North.

We passed both the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act and the Canadian Environment Protection Act.

In Toronto in 1988, Canada hosted the first international conference with politicians actively present on climate change. Gro Brundtland delivered a powerful keynote address, and Canada was the first western country to endorse the historic recommendations of the Brundtland Commission, and the first to embrace the language of “sustainable development.”

In 1991, we signed the Acid Rain Accord with the United States, an issue we had been working on since taking office in 1984.

At the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, we helped bring the U.S. on board in support of the Convention on Climate Change, and we were the first industrialized country to sign the Bio-Diversity Accord Treaty.

Following the remarkable discovery by two British scientists in 1985 that a hole in the ozone layer had appeared over Antarctica — there was a hole in the sky — world action was urgently required.

And so came the Montreal Protocol, organized by Canada in 1987, which a New York Times headline has called: “A Little Treaty That Could”. Could it ever, as it turns out.

It has cut the equivalent of more than 135 billion tonnes of carbon-dioxide emissions, while averting the collapse of the ozone layer and enabling its complete restoration by the middle of this century.

Former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan has called the Montreal Protocol “the most successful international agreement to date.”

As The New York Times reported in 2013: “The Montreal Protocol is widely seen as the most successful global environmental treaty.”

In The Guardian, Mario Molina, the Nobel co-laureate in chemistry for his work on ozone depletion wrote that: “The Montreal Protocol has a claim to be one of the most successful treaties of any kind.”

Professor Molina continued: “The same chemicals that attacked the ozone layer also warmed the climate. Thus, in phasing them out, the Montreal Protocol has made a large contribution to protecting the world’s climate.

“The Montreal Protocol is, therefore, a unique planet-saving agreement.”

That was 30 years ago.

Thirty years on, we now witness daily examples of the perfect storms of global warming—the hurricanes slamming the Gulf Coast, incubated in the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, wildfires from California to Australia that conjure up images of Dante’s Inferno, and the inexorable shrinking of the polar ice cap.

What were trends in 2006 — the year I was honored to be chosen the Greenest Prime Minister in history by Canadian environmentalists — are now part of the new normal and are more frightening for that fact. More Category 4 and 5 hurricanes, hundred-year floods now seemingly become an annual occurrence, more severe tornadoes, more devastating hurricanes, rising sea levels, higher storm surges, an earlier spring, hotter summers and warmer winters.

Now is the time to act. Now is not the time to imprison ourselves in ideological arguments. Now is the time to test the outer limits of what we can achieve for future generations.

The climate change issue is admittedly a difficult problem to address but from my own experience as prime minister, I would say there are three elements to Canada playing an important and influential role on the environment: First, leading by example, with a clean-hands approach, claiming the high ground. Second, engaging the Americans at the highest level of government which, because of geography and history, no other nation can do. Third, involving industry in solutions.

The clean hands approach provided us moral leverage when I was given the high honour of addressing a joint session of the U.S. Congress in April 1988.

Here’s what I told them: “You are aware of Canada’s grave concerns on acid rain. In Canada, acid rain has already killed nearly 15,000 lakes, another 150,000 are being damaged and a further 150,000 are threatened. Many salmon-bearing rivers in Nova Scotia no longer support the species. Prime agricultural land and important sections of our majestic forests are receiving excessive amounts of acid rain.”

And here’s where the clean hands came in, allowing me to put the onus on the Americans to act. “We have concluded agreements with our provinces to reduce acid rain emissions in eastern Canada to half their 1980 levels by 1994. But that is only half the solution—because the other half of our acid rain comes across the border, directly from the United States, falling upon our forests, killing our lakes, soiling our cities.”

I continued: “The one thing acid rain does not do is discriminate…It is damaging your environment from Michigan to Maine and threatens marine life on the eastern seaboard. It is a rapidly escalating ecological tragedy in this country as well.

“We acknowledge responsibility for some of the acid rain that falls on the United States. Our exports of acid rain to the US will have been cut in excess of 50 percent. We ask nothing more than this from you.”

I left the joint session of Congress with this question: “What would be said of a generation of North Americans that found a way to explore the stars, but allowed its lakes and forests to languish and die?”

Fortunately, we averted such a damaging verdict of history, by forging ahead until we got an agreement. We must follow the same strategy again. No one complains about acid rain anymore because it not around much anymore.

Just recently, on November 11, the Canadian Press reported:

“Canada’s plan to meet its greenhouse-gas emissions targets is among the worst in the Group of Twenty, according to a new report card on climate action.

“Climate Transparency issued its annual report Monday grading all the countries in the G20 with large economies on their climate performance and finds none of them has much to brag about.

“Canada, South Korea and Australia are the farthest from meeting targets to cut emissions in line with their Paris Agreement commitments… Canada’s per-capita emissions are the second highest in the G20, behind only Australia.”

So, what are we, as Canadians, to do?

Lead.

As our politicians gather in Ottawa for the opening of a new Parliament, I would encourage them to dream big and exciting dreams for Canada. They should keep their eyes on the challenges confronting Canada’s golden future and avert them from constant and misleading public opinion polls and focus groups that dictate the nature of many of their public policies, often choosing the easy way out.

Otherwise, when they leave office and history says: “What visionary or courageous policies did you introduce that improved Canada’s environment and perhaps inspired the world?” If the answer is “none, but I was very popular”, then, they will have an eternity to reflect on the tough, unpopular but indispensable decisions for Canada‘s progress they avoided, in order to bask in the fleeting sunlight of high approval ratings that served only their own personal vanity and interests.

They must realize that there still is place for daring in the Canadian soul.

As St. Thomas Aquinas admonished leaders everywhere, and for every age: “If the highest aim of a captain were to preserve his ship, he would keep it in port forever.” That was not my way when I was prime minister and it cannot be our way now. In fact, Minister Catherine McKenna has worked in a highly challenging area for the last four years in a competent manner in which she sought to advance our national interest as she saw it.

All those who seek to lead would do well to remember the words of Walter Lippman that “these duties call for hard decisions…because the governors of the state…must assert a public interest against private inclination and against what is easy and popular. If they are to do their duty, they must often swim against the tides of private feeling.”

In my opinion that is how it should be today.

Leaders are not chosen to seek popularity. They are chosen to provide leadership. There are times when voters must be told not what they would like to hear but what they have to know. There is a quotation from the book of proverbs carved into the Nepean sandstone over the west arch window of the Peace Tower of the Parliament in Ottawa that serves as both an inspiration and a warning for all who seek to lead. “Where there is no vision, the people perish”.

The true test of leadership hinges on judgments between risk and reward. Change of any kind requires risk, political risk. It can and will generate unpopularity from those who oppose change, but it is the job of political leaders to convince Canadians that there is opportunity to be found in accepting the challenge because achievement occurs when challenge meets leadership.

Those who aspire to national leadership must craft an agenda that responds to the hopes and aspirations of all Canadians. Small, divisive agendas make for a small, divided country. It is not enough to simply please “the base.”

Leaders should be blessed with greater ambition than simply satisfying subsets of the population and they should leave niche marketing strategies to retailers.

But leadership is not simply possessing the vision that recognizes the need for action or change, it is also the process involved in making the case for action or change.

In the final analysis, successful leaders do not impose unpopular ideas on the public, successful leaders make unpopular ideas acceptable to the nation. This requires a compelling and convincing argument, one made from conviction and combined with the will, the skill, and the disciplined commitment to make that argument over, and over, and over again.

Time is the ally of leaders who place the defence of principle ahead of the pursuit of popularity. History has little time for the marginal roles played by the carpers and complainers and less for their opinions. It is in this perspective that great and controversial questions of public policy must be considered.

History tends to focus on the builders, the deciders, the leaders — because they are the men and women whose contributions have shaped the destiny of their nations. As Reinhold Niebuhr reminded us: “Nothing worth doing is completed in our lifetime; therefore, we must be saved by hope. Nothing fine or beautiful or good makes complete sense in any immediate context of history; therefore, we must be saved by faith”.

As difficult as the process may be to arrest and to mitigate the effects of global warming, the work cannot be left to the next fellow. The stakes are too high, the risks to our planet and the human species too grave.

We are all on the same side, determined to leave a better world and a more pristine environment to all succeeding generations.

May our leaders summon the wisdom and courage to make this happen, knowing that history will celebrate such achievement and their children and grandchildren will be proud and grateful to them for such a brilliant and decisive legacy.

Brian Mulroney was Canada’s 18th Prime Minister from 1984-93.