Step One, Mindset Shift: Innovation in the Social Good Sector

Our country’s charitable organizations risk becoming obsolete. Recent research from both the Rideau Hall Foundation and CanadaHelps has found troubling trends in giving behaviour that charities, donors, and policy makers must act on before it is too late. Fortunately, the same research holds the key to solutions for those charities willing to make the next great leap—which will need to begin with a mindset shift.

Teresa Marques and Marina Glogovac

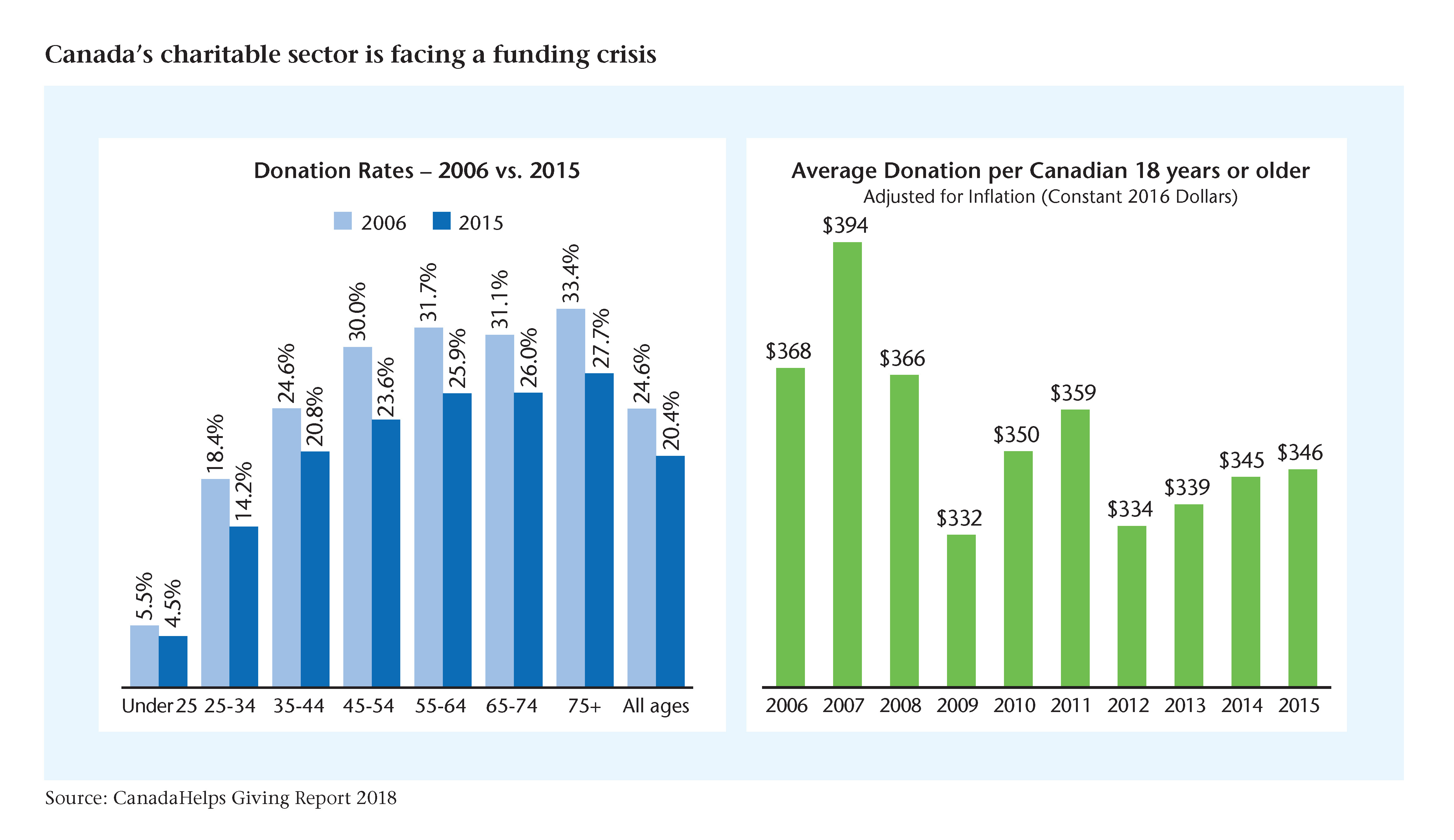

The 2018 Giving Report by CanadaHelps found that between 2006 and 2016, Canada’s population grew at a rate three times faster than the size of donations over the same period. This also reflects fewer donors, with just one in five Canadian tax-filers making donations in 2016, down from one in four in 2006.

In partnership with Imagine Canada, the Rideau Hall Foundation sponsored Thirty Years of Giving in Canada, a landmark study that mapped donations and giving patterns in Canada from 1985 to 2014. It produced three important findings:

First, Canada’s charities and non-profits are too dependent on aging donors: People aged 50 and over now account for three quarters of all donations, while those 70 and older make up 30 percent. Second, the long-term viability of the charitable sector in our country will require an increase in donation rates among younger Canadians. Finally, in the absence of better youth engagement, the effectiveness of the charitable sector will be severely restricted. There are several forces at work in changing giving behaviour, including disruptive technology, demographic changes, and cultural shifts. Increasingly, donors are influenced by their peers and are less incentivized by a tax receipt.

The most recent Global Trends in Giving report from the Public Interest Registry reveals that 41 percent of donors worldwide have given to crowdfunding campaigns that benefit individuals, nearly half (44 percent) for expenses related to medical treatments and family emergencies. At the same time, social media is now the leading communications tool that inspires giving. For example, 18 percent of donors have given through Facebook fundraising tools and 88 percent say they will likely to do so again. Of most concern to charities, it appears that a significant percentage of donors through crowdfunding believe that they donate less money to traditional charities as a result. All these numbers lead to an inescapable conclusion: Many young donors no longer see any lines separating charitable giving and other forms of giving. To them, giving is simply that—giving. And as the months and years pass, the informal, flexible and increasingly innovative ways of giving—the ways that appeal to them most—has the potential to squeeze out traditional charitable giving and put charitable programs at risk if they fail to adapt. Faced with this reality, we need innovation in our country’s charitable sector like never before.

Why should we care about the survival and success of the charitable sector? Healthy charities in Canada are important for all Canadians, and we’re unlikely to truly understand the social and economic gaps left by failed charities until it is too late. These organizations reflect the increasing diversity of our country; they engender greater inclusion in all aspects of Canadian life; they fill gaps in the health and welfare of people and communities that our governments are slow or unwilling to close; and they can spur transformational innovation by injecting seed capital into novel research in a manner that traditional funding mechanisms do not often allow for. The critical role charities play has always required innovative approaches to problem solving. In their recent book Ingenious, David Johnston, Rideau Hall Foundation chair and Canada’s 28th Governor General, and Tom Jenkins, former CEO of OpenText, focus on this country’s most influential innovations.

Breakfast for Learning is one example. Set up in Toronto in 1992, the non-profit program was the world’s first to help schools make sure kids get the nutritious breakfasts and lunches they need to fuel their minds for learning. It grew quickly to include some 1,600 schools across Canada, serving 600 million meals to almost four million young students. As Johnston and Jenkins make clear, Breakfast for Learning is a resounding demonstration of the role schools play not only to instruct, but also to equip students with the basic physical capacity to learn. Understanding that the path to learning runs through the stomach, and then acting on that knowledge, is innovation.

So how should charitable organizations change? There’s no question that the charitable sector must innovate to succeed. The need for innovation is not in the way charities attack societal issues, however, but rather in the way they adapt to survive and thrive amid the exponential rate of digital and cultural change we’re currently experiencing. While they should keep looking to innovate in ways such as Breakfast for Learning did, that kind of innovation alone is not enough. Organizations should themselves embrace innovation in how they work and how they are sustained: they should become more adept at explaining the societal value of their services or cause to young Canadians; they need to find ways to be more transparent, earn higher levels of trust, and build long-term donor loyalty. They also must also truly embrace digital transformation. Technology is propelling innovation, disruption, and a rapid pace of change, but digital transformation is much more. It’s not about simply adopting technology into organizational processes-such as creating a website, having an online donation form, or investing in new fundraising methods. Real transformation will require looking beyond just fundraising and instead developing a wholesale digital transformation strategy. This will require a mindset shift both within charitable organizations and by those who support them in the public and private sectors. Digital transformation is a holistic approach to integrating digital strategy and digital technologies into an overall organization. It is strategic and intentional change, enabled by technology but successful only through strong leadership, a learning orientation, cultural alignment, and innovation. Digital transformation is all-encompassing. Charities must think about their human resources and organizational strategies: what are their processes for a digital world, and how can they hire people with the right digital skills and mindset? They must think about their technology infrastructure and connectedness. They must have a content strategy to think about what their story is and how they are telling it, a social business strategy, and a channel strategy to ensure they are where their donors are.

Charities must develop data strategies, determine what they must collect and store, reconsider what questions they’re asking, and identify their key performance indicators. The process will involve leveraging technologies and their impact on potential donors in a strategic (not reactive) way. For this change to be successful, it must also be sustainable. Transformation that’s sustainable stems from the genuine makeup of an organization. The change in any charity must be faithful to its mission and vision; it must reflect an accurate understanding of the competitive landscape; it must take into consideration the needs of partners; and it must be based on a thorough review of organizational assets, gaps and competencies. Above all, change must deliver increasing value to contributors and beneficiaries, and to Canadians who neither give nor receive directly.

Transformation comes from leadership, and it is both ambiguous and messy. The statistics show that most digital transformations within all sectors fail, and success will be even more challenging in the traditionally risk-averse charitable sector. Success will require funder and board support, and agreement that charities need to invest in themselves. It requires courage and determination, embracing an innovation mindset, and cultivating a willingness to fail.

Healthy charities are important for everyone because they fill gaps, build on success, and include the excluded. But the status quo is a death knell for Canada’s charities. Our country’s charitable sector is at risk and only wholesale rethinking and reform will do. Canadian charities and non-profits have long shown that they can be innovators when it comes to tackling problems with limited resources. That spirit of ingenuity is needed now more than ever.

Teresa Marques is President and CEO of the Rideau Hall Foundation.

Marina Glogovac is President and CEO of CanadaHelps.