Sri Lanka as a Cautionary Tale in Conflict Resolution

While the entirely avoidable chaos unfolding in Western democracies sucks up all the oxygen, something important is happening in one of China’s purchased pearls.

EPA

EPA

Lisa Van Dusen

November 22, 2018

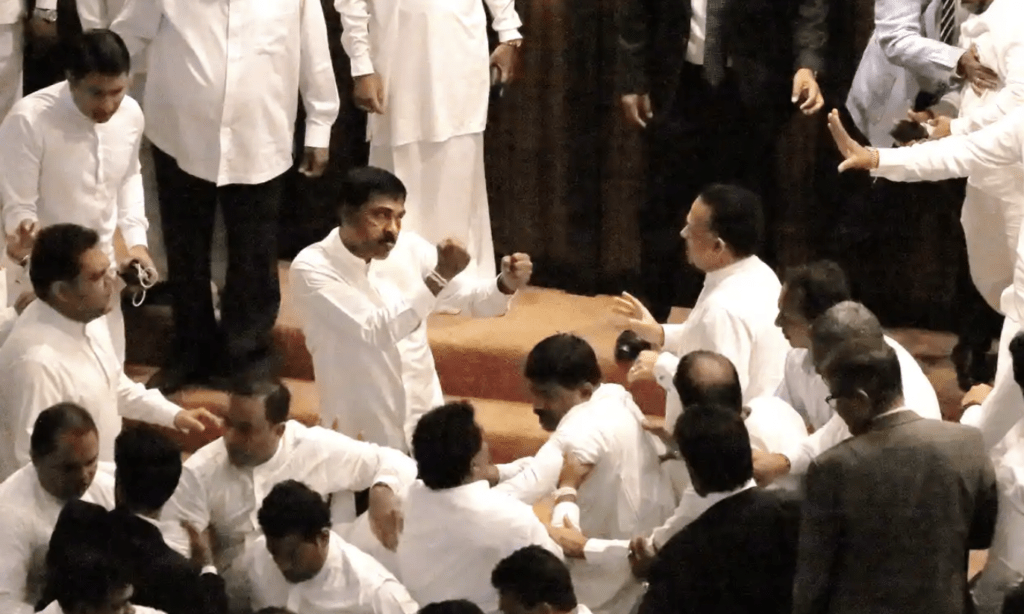

The latest entry in the global parliamentary brawl reel, the political junkies’ equivalent of piano-playing cat, came from Colombo, Sri Lanka, last week. It played out over two days and included broken chairs, projectile chili paste and a pile-on of Ukrainian proportions.

As with many parliamentary pandemonium scenes, this one was the kinetic manifestation of larger, higher-stakes political and geopolitical ructions. In Sri Lanka’s case, they involve the country’s existential drama and the rapidly rising superpower that has played a determinative role in it.

In 2009, after almost 30 years of civil war, the separatist guerrillas of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) were wiped out in what stands as one of the most brutal insurgency-obliteration operations conducted in recent times. After years of inconclusive peace talks, Sri Lankan government forces, under President Mahinda Rajapaksa and with financial and military support from China, kettled the Tamil Tigers in their stronghold in northern Sri Lanka, banned journalists from the area and massacred the LTTE, including its leaders, ending the civil war.

There were allegations of war crimes on both sides, but particularly on the part of the government. “Tens of thousands of civilians were killed in just a few months at the end of the civil war in 2009, in what [Rajapaksa’s] government cynically referred to as a “no-fire zone”,” wrote Freedom from Torture Chief Executive Soya Sceats in the Guardian last week. The chaos in the Sri Lankan parliament last week was generated by Rajapaksa’s return in the form of a stunning hostile takeover as an unelected prime minister.

Diplomacy was the preferred avenue to peace, especially by democracies that equated stability with respect for human rights, not with the absence of them. Peacemakers — Richard Holbrooke, Sérgio Vieira de Mello, George Mitchell — became as well-known as the figures they refereed. They have no contemporary equivalents, and there’s a reason for that.

Since 2009, China’s role in Sri Lanka has grown, including with the purchase of the port of Hambantota as a link in Beijing’s “string of pearls” Indian Ocean strategy — the nautical iteration of China’s massive Belt and Road project. As with countries across eastern Europe, Africa and South America, the accession of Sri Lanka to the class of nations now beholden to China based on the quid pro quo of a “debt trap” has increased Beijing’s leverage in determining its political outcomes in a way that makes Russia’s attacks on democracy look incompetent.

The Sri Lanka model of intra-national conflict resolution marked the end of an era when negotiation was favoured over military solutions. From the Oslo Accords to the Dayton Accords to the Good Friday Agreement, diplomacy was the preferred avenue to peace, especially by democracies that equated stability with respect for human rights, not with the absence of them. Peacemakers — Richard Holbrooke, Sérgio Vieira de Mello, George Mitchell — became as well-known as the figures they refereed. They have no contemporary equivalents, and there’s a reason for that. From the Israel-Palestinian stalemate to the Rohingya ethnic cleansing (Myanmar finalized its $1.3 billion deal with China for the string-of-pearls port of Kyaukpyu earlier this month) to the seemingly infinite hell of Syria, asymmetrical conflicts today are generally not being resolved through negotiations.

When an authoritarian superpower deals with its own fear of instability by building a surveillance state and detaining at least one million Uighur Muslims, it won’t be using its economic leverage to normalize more civilized conflict resolution strategies elsewhere. Military and intelligence solutions are far easier to execute in the absence of functioning democracy; people generally don’t vote for their own extermination, or for people capable of such acts.

When Louise Arbour, the former Canadian Supreme Court justice who was then UN high commissioner for Human Rights, visited Sri Lanka in October 2007, she described it as a country where “the weakness of the rule of law and prevalence of impunity are alarming”. Amid shifting global power, those words are beginning to be true of more and more countries.

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor of Policy Magazine. She was Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.